Question: It seems that sometimes I can’t tolerate interruptions to my self-absorption. Irritations, big and small, intruding on my desire to settle into the false comfort of ego, can seemingly produce a “me” that is argumentative, difficult, and short-tempered. I’m guessing that I’m not alone in this. How can we engage emotional provocations and self-centeredness in ways that turn us toward dharma practice and life?

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: I would say you have already taken the most important step toward answering your question—that is, noticing a habitual pattern that causes a painful result. I am guessing that you noticed this habit while observing your thoughts in meditation. Until we can see for ourselves that our own actions of body, speech, and mind are creating the pain, we think that someone or something outside ourselves (over which we have no control) has to change in order to put an end to the pain. When we notice that it is our own thoughts that make us want the world to change, so as to accommodate our own desires or aversions, we then have choice. We can cling to that thought, believe it, feed it, and watch it grow from irritation to rage, or from attraction to thirsting desire. Or, in zazen, we can note the first arising of the thought, remember that it can lead to severe pain, and decide to let it go by returning our attention to breath, posture, or physical sensations (which are all occurring in the present moment). In other words, we can see that we do have some control over which thoughts we feed and cling to and which ones we let go.

This is easier said than done. Many of us have some pet thoughts and attitudes, especially about “me” and the world according to “me,” and we are very reluctant to let them go. It is useful when we hear ourselves insisting on our point of view to say to ourselves, as my teacher often did, “Maybe so.” He also said, “You don’t have to invite every thought to sit down and have a cup of tea.” (One of my favorite bumper stickers is, “Don’t believe everything you think.”)

In addition to letting go of painful thoughts, it is very beneficial to cultivate positive thoughts. In this regard, two teachings I deeply appreciate come to mind. One is the view of reality in the Avatamsaka Sutra where everything is totally connected with everything else as Indra’s Net, where the universe is a vast net with a jewel at each intersection of the threads. Each jewel is reflected in every jewel and every jewel is reflected in each jewel. To me, it is a vivid image of the teaching of no separate self or dependent coarising.

The other teaching I appreciate and encourage is the cultivation of gratitude. This life of ours is a gift. There is a teaching in the Tibetan tradition that everything we have comes to us through the kindness of others (including our bodies), and we have had so many rebirths that all beings have been our mother in some life. Therefore we should be as grateful to all beings as we are to our mother in this life.

Meditation is the key resource for studying our mind and cultivating more skillful habits of thought. Zen teacher Kobun Chino once said, “The more you sense the rareness and value of your own life, the more you realize that how you use it, how you manifest it, is all your responsibility. We face such a big task, so naturally such a person sits down for a while. It’s not an intended action, it is a natural action.”

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: The moment we experience disruption in our practice or in our life is in fact an opportunity, or doorway, to let go and radically open. What we often do instead is react with aversion, tensing our body and becoming angry. We are trying to maintain continuity of our sense of self, our focus, our agenda. This is the opposite of meditation practice. In our meditation practice we should not have a fixed goal, idea, or agenda to attain. Rather, our practice should support us in recognizing each moment in its aliveness and in connecting with clear, open awareness. Open awareness is not something we produce, but something we recognize. As we continue to practice meditation, we become increasingly familiar with openness. We discover that openness is the source of all positive qualities, such as loving-kindness or compassion for another.

Ego is a complication, or obscuration, of this fundamental openness. Reading the question that was posed we can hear this complication expressed. There is a “me” who is absorbed and now interrupted, a “me” who becomes argumentative with an “other” who is so rude to interrupt, or so loud, etc. This back and forth internal dialog, which of course can become external and lead to many unpleasant complications and dramas, can also simply be abandoned on the spot if one is willing to experience in a raw and direct way whatever sensations and feelings are present. If we simply feel what we feel—without judging or elaborating—the feelings and sensations come, stay for a moment, and then leave on their own. This is a natural process when we don’t interfere by engaging our conceptual mind. In this process we can directly observe this “who” that is interrupted.

Naked observation, without commentary or analysis, is very powerful. In the presence of our naked observation, the structure of ego dissolves. It simply cannot remain if we are not feeding it with our conceptual mind. So what begins as a feeling of interruption, insult, or injury, instantly becomes a reminder to observe directly. As we observe, our reaction dissolves, and what remains is openness. And there we rest, or abide. Even if this is only a glimpse of openness, perhaps lasting for only thirty seconds, it is the foundation upon which to build one’s dharma practice. Remember, the space that opens up is the source of all positive qualities, which do not have to be coerced or forced but are naturally and increasingly available as we become more familiar with open awareness. We have so many challenges in life that can become opportunities to let go and open. In this way, irritation itself becomes the doorway to the inner pure space of our natural mind, the mind of all the buddhas.

Narayan Helen Liebenson: Shining the light of awareness on self-absorption, impatience, and short-temperedness is the first step in letting them go. In a way, we should thank people who interrupt and annoy us because they are interrupting our self-absorption as well. As Thai monk Ajahn Chah said, we must become aware of how weighty our burdens are before we are able to put them down. Developing sensitivity to inner suffering, and the consequences of this suffering for others, helps us realize that there is no other choice than to dedicate ourselves wholeheartedly to a path of awareness.

As we untie the inner knots of habitual conditioning, we are aware that impatience is a mental state and there is no need to identify with it or justify it. With awareness and discernment, we observe our inner reactions and negative mental states with patience and compassion. We are not trying to suppress or condemn the sensations and emotions, which would only add aversion to aversion. Rather, we are strengthening our capacity to remain calm and unshaken in the midst of momentary colorations of mind. Awareness offers us the opportunity to pause and discern the mental state that is occurring. Then we can investigate and ask: Is this mental state wholesome? Is it to be cultivated or let go? Is it possible to see that this thought is just a thought, that this feeling is just a feeling? In this way, we regain inner balance.

The wisdom of restraint is often called for. This means resolving not to act or speak when in the grip of negative emotions, and not lashing out at those who interrupt or annoy you. Acting on aversion reinforces the habit of aversion. You might stop and ask yourself from time to time, What am I practicing? When we practice impatience, the result is more impatience. When we practice loving-kindness, the result is more loving-kindness.

All of this requires patience and perseverance. Most of us know better than to blame others for our reactions, yet we do so anyway because of the seeming strength of conditioning. We alone are responsible for our reactions, no matter how provoked we are. This is a difficult lesson to learn but ultimately it means we are not under anyone else’s power. We can learn to respond to emotions with intelligence and kindness instead of reacting to outer stimuli. Meditation teaches us to look within and respond with the heart. The good news is that when we use such means as patience and compassion, they become natural and organic responses. In this way, difficulties turn into material for liberation.

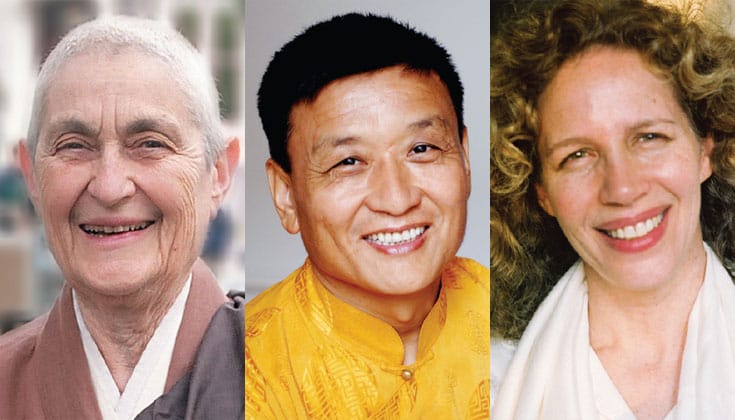

Zenkei Blanche Hartman was a Zen teacher and former abbot of the San Fransico Zen Center.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche is a lineage holder of the Bön Dzogchen tradition of Tibet.

Narayan Helen Liebenson is a guiding teacher at Cambridge Insight Meditation Center.