Question: How do we retain passion in life and still follow the teaching that we should accept all of life with equanimity?

Narayan Helen Liebenson: I don’t think there is an inherent conflict between living passionately and living with equanimity. Not only can passion and equanimity coexist, they can work together harmoniously.

When I use the word “passion,” I am referring to loving engagement and dedication. This implies a sense of inner vitality and aliveness, a love of learning, and the capacity to work with difficulties in a creative way. Alleviating suffering, engaging in any kind of art form, living in this world with wholeheartedness, and discovering the truth of things—all of these require passion, devotion, and dedication.

You ask about “retaining passion.” I think the issue is more one of how to cultivate wise passion that is grounded in care and love. If the kind of passion being cultivated involves attachment, life will be lived in a narrow and contracted way. Whenever we attach to things being a certain way and according to a personal agenda, we make problems for others and ourselves. By contrast, non-attachment brings spaciousness and inclusiveness.

There are no “shoulds” regarding equanimity. We cultivate equanimity because it lessens the suffering in life. Equanimity means responding to the conditions we encounter with inner balance and relaxation. It’s about responding with wisdom and compassion rather than reacting with aversion or clinging. Being equanimous doesn’t mean being compliant, complacent, or resigned. And it has nothing to do with indifference. The Buddha said that indifference is the near enemy of equanimity, because indifference is all too easily mistaken for it, yet equanimity is a very different quality of mind. As one of my early teachers, Tara Tulku Rinpoche, once said, equanimity means that everything is “equally near,” which implies an intimacy with all things.

So we are cultivating a passion for a vision of how things could be, and at the same time we are learning how to be equanimous and non-resistant to how things are. We always have the potential to encourage what is beautiful, whether it’s between two people, or between two countries, or whether it arises from engaging in an art form, or from simply sitting in meditation.

The passion to contribute what we can is a form of love. Passion only turns into a problem when we try to control the outcome of our efforts. When we find others aren’t cooperating with our vision, or are in direct opposition to it, what may have begun as care, passion, and love can turn into burnout, anger, frustration, disappointment, irritation, and impatience. This is attachment, not love.

Ultimately, we are trying to cultivate a passion for life rather than for the things of life, a passion that expands our heart and our sense of what is possible in this world. This kind of passion is love, not just for a select few, but for all. In this way, passion and equanimity come together in love and in wisdom.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: This “passion in life” that you want to retain, is it different from wholehearted engagement in the practice of the Buddha Way for the benefit of all beings? Or is it different from deep appreciation and heartfelt gratitude for the gift of life? Does it have anything to do with a gaining idea or getting something you don’t think you have?

According to my dictionary, the origin of the word “passion” is from the Latin verb passus, meaning “to suffer.” In English, passion refers to strong emotion, which could be either positive or negative, either love or hate. “Equanimity,” on the other hand, means evenness of mind, composure, serenity, tranquillity. It is true that in the buddhadharma we are encouraged to cultivate the four immeasurables, or heavenly abodes: loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity. I don’t see that cultivating equanimity would discourage loving life, or loving the world, or being joyful, but it would perhaps temper strongly held preferences and opinions, and the emotions that accompany them.

My teacher, Suzuki Roshi, encouraged us to appreciate “things as-it-is.” He also said, “Just to be alive is enough.” Many Zen teaching stories end with the punch line, “Just this!” or “just this is it.” This teaching of accepting all of life with equanimity, or even with gratitude, is a very compassionate teaching. The events of our life will be whatever they will be, depending on the causes and conditions in any given moment. Of course, our intentions and our actions of body, speech, and mind are part of those causes and conditions. Whatever arises, we are free to choose whether to respond with passion or equanimity.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: Enlightenment is not a state of passivity or indifference. Equanimity involves seeing through your wisdom eye and not through your negative emotions, such as anger or attachment. It is important to understand that it’s possible to live life with equanimity as well as with enthusiasm, inspiration, and a loving heart.

It seems in the West we associate passion with uncontrolled emotion. Emotion drives us toward what seems shiny and promising. But it is possible to experience strong emotion, or strong enthusiasm, or inspiration, without being driven by emotion. You must guide emotion—You are the source of that emotion, and also the driver. You guide that emotion and live and act with it, but you are in control. Equanimity means total control of our emotions.

While we usually equate control with tension and effort, that’s not the case here. A good athlete will perform with grace and strength, with no extra tension. A confident and skilled driver will drive a car with good control, but not tension. If you drive too loosely, and without respect for the conditions of the road and the capacity of the vehicle, you will lose control of the car. But if you are a good driver, you are in relation to all conditions present and are not tense. The fundamental requirement for control is that you are open. You are open and you are aware in that openness.

In Tibetan Buddhism there is a saying that samsaric beings are controlled by their karma and their emotions, while enlightened beings are not. If we are honest, we cannot say we are not controlled by our emotions, but how much we suffer is a question of how much we are controlled by our emotions. Are you guiding your emotions, or are your emotions propelling you in certain directions? With open awareness, you are not the victim of conditions; rather, you are able to guide your emotional energies, and are therefore free to experience curiosity, enthusiasm, and joy in living.

You can be open and love someone and not be attached. You can be excited about something without being bound by the expectation of a specific outcome. Unfortunately, people often become excited about an imagined outcome rather than experience joy in the moment for its own sake. You can just be excited. Open excitement! Open joy! This very openness is what makes the experience of love strong. One might call it passionate, but it is open—and that is what makes the difference between love that benefits and love that causes us to suffer. When you are open, you have more ability to guide your love, and you are less a victim of the pain of love, because if something goes wrong, you easily let it go. Openness has a lot to do with letting go. When you let go, you reconnect with unconditional openness and discover love, joy, and compassion, which arise naturally.

Our equanimity comes from open awareness itself, and when we connect with that source again and again, our life is dynamic and alive—not passive, dull, or disconnected. Each time you let go of your attachment, you reconnect with open awareness. This is what is known as the path. We continuously recognize that the source of our love is not in the other person, and that the source of our enthusiasm is not in this job or that project. This frees us to engage fully in life and to allow our life to become our path.

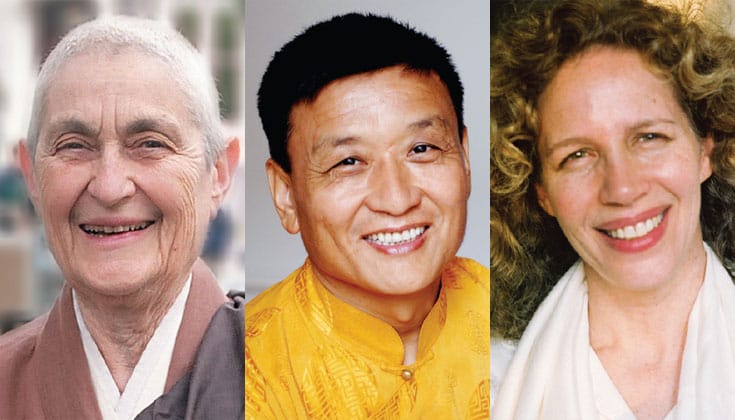

Zenkei Blanche Hartman is former abbess of the San Fransico Zen Center.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche is a lineage holder of the Bön Dzogchen tradition of Tibet.

Narayan Helen Liebenson is a guiding teacher at Cambridge Insight Meditation Center.