Question: Is there a Buddhist perspective regarding practitioners who become afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia? Since the mind is the primary tool with which we work toward the realization of buddhanature and enlightenment, what does it mean if one loses that mind, or loses the capacity to practice, long before one dies?

I’ve been able to find teachings and information on Buddhist skills for caring for loved ones with dementia, but I cannot seem to find anything on the potential quandary of practicing Buddhism if confronted with dementia oneself. What happens to our right effort if we lose the ability to practice or to work with our mind? And what happens to the skillful means we developed for our own death?

Narayan Helen Liebenson: As far as I know, there is nothing in the sutras that specifically addresses this question. However, in Buddhist teachings, illness is one of the four heavenly messengers (the others are old age, death, and renunciation). Dementia is obviously a form of illness. As such, it is a wake-up call. The Buddha wanted us to reflect on the fact that we don’t have forever to practice; we may even lose the use of our minds at some point. In reflecting on the impermanence of youth, health, and longevity, we may find more motivation for practice and truly reorder our priorities in life. In other words, we may do our best to live the teachings of the Buddha right here and now.

Regarding your question about whether it’s possible to practice with Alzheimer’s disease or dementia, I have some firsthand knowledge, having observed a meditation teacher at Cambridge Insight Meditation Center who had dementia during the last few years of his life. In the early stages of his illness, he would frequently forget what he was about to say. As time went by and the illness progressed, often he didn’t know where he was or what to do next. At first this caused him a great deal of anxiety. However, because of his many years of dedicated practice, as well as being with a life partner who helped him enormously, he began to look more directly at the anxiety itself and he learned to be less afraid of forgetting. In other words, the suffering lessened because he became more at peace with himself. During the more advanced stage of his illness, this usually was not possible.

So some practitioners may be able to apply the teachings to an extent as they begin to experience mental deterioration. What may be important is not to hold on to idealized ways of how things should be but to practice surrendering to how things are. For example, if you’re frightened or angry, be aware that fear and anger are happening.

For me, the two essential components that are necessary in this kind of situation are committed bhavana (mental development) and noble friendship. Noble friendship is contact with fellow practitioners, which is essential as our bodies and minds weaken. We benefit from the love and support of those who are patient and experienced in the practice. This applies not only if one is suffering from dementia — even in old age we can see how interdependent we are, as we become increasingly dependent on those around us. It seems to me that an aspect of one’s practice is to allow others to help. In cultivating wise friendships with those we trust, we are more likely to be in good hands when things break down. Those holding the “higher ground” can be a refuge and remind us of who we really are.

Perhaps with an immense depth in the practice, it is possible to experience life from a deeper place, even if the brain breaks down before death. Nisargadatta Maharaj, a great Hindu teacher who lived in India, implied that he observed himself becoming senile and was not at all bothered by it because he knew so clearly that he was neither his body nor his mind.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: I don’t know of any explicit teaching on practicing with dementia, except perhaps this mention from Judith Lief in her book Making Friends with Death:

I remember hearing the renowned Tibetan teacher His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche talk about getting older. He was in his late seventies at the time. He said that as you get older, you go to extremes, and fundamentally you have only two choices: extremely vast mind or extremely petty mind. There is less and less room in the middle, so you have to make a choice; you can only go one way or the other. Khyentse Rinpoche’s own choice was clear: he continuously radiated that vastness of mind.

I am grateful that I have not yet personally had the experience of dementia, except for occasional short-term memory lapses (I am currently eighty). However, my uncertainty about the very question you have asked is an inspiration for me to practice diligently — now, while I can.

I have had occasion to observe some practitioners who are practicing with dementia. One is a student who practiced quite sincerely with me in the past but whom I had not seen for a while. She told me that she had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and wished to work with me while she could. I suggested that we study precepts together and sew a rakusu (a small dharma robe worn by lay practitioners who have taken refuge and received the sixteen bodhisattva precepts in the Soto Zen tradition) in preparation for jukai (a ceremony for receiving precepts). Her sister has very kindly brought her to the center to study and sew with me regularly. What I am noticing is that her sincere intention is clear in the midst of her confusion with details, and her disposition brims with gratitude and sweetness.

Then there is a dharma sister with whom I began practice in 1969. As her Alzheimer’s progresses, she bubbles over with childlike affection, greeting all old acquaintances with enthusiastic hugs and delighted expressions of love.

The third person is the great Cambodian teacher Maha Ghosananda. The last time I saw him was at a large dharma teacher’s gathering at Spirit Rock Meditation Center. He clearly seemed to be affected by some kind of senile dementia. When I approached him to pay my respects, he was sitting alone, smiling broadly. As I came closer, I was overwhelmed by a palpable physical experience of him “suffusing love over the entire world, above, below, and all around without limit,” as it says in the Metta Sutra. Seeing directly that such a result is possible with a lifetime of practice, I am inspired to practice even more diligently. As Suzuki Roshi said, “Zen is making your best effort on each moment forever.”

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: A basic principle of the Buddhist teachings and meditation practice is to feel the support of practice in moments of difficulty in everyday life situations. Every dharma practice we do prepares us to face our conditioned patterns — whether we’re dreaming or sleeping, experiencing sickness or adversity, or even dying. If, in your meditation practice, you clear away anger and cultivate loving-kindness, when you later encounter a challenging situation, such as facing a perceived enemy, love naturally awakens. If you practice awareness throughout the day, as you fall asleep, awareness serves you in dreams, which become more lucid and provide opportunities to transform conditioned experiences into experiences of higher realization. By practicing with clear light as you enter sleep, experiences of clear light will awaken at a time when you normally lose awareness.

If you become diagnosed with Alzheimer’s or dementia, prepare as you would for death. Then, in those moments when you lose the reference points of self, clarity will naturally dawn. If you become familiar with love, compassion, joy, and equanimity through your practice, then as you begin to lose control, these qualities will naturally shine through. Through the practice of cultivating peace and clarity, they will penetrate and pervade all conditioned experiences.

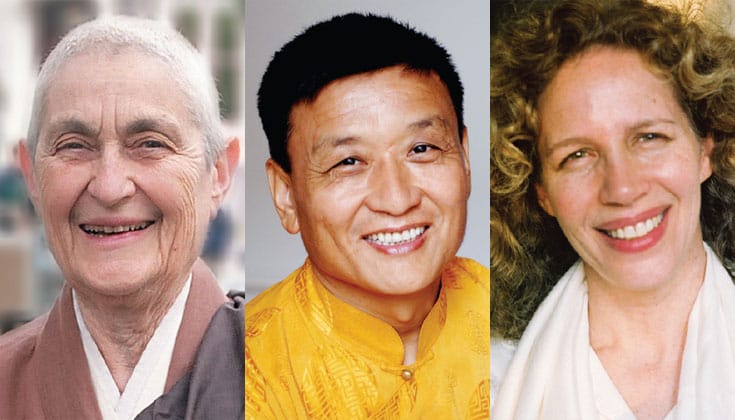

Zenkei Blanche Hartman is former abbess of the San Fransico Zen Center.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche is a lineage holder of the Bön Dzogchen tradition of Tibet.

Narayan Helen Liebenson is a guiding teacher at Cambridge Insight Meditation Cent