Question: I received a breast cancer diagnosis in January and have almost finished chemotherapy, which will be followed by radiation treatment. Many cancer survivors say that attitude is key to survival. I understand that having hope and a good attitude, eating the right food, exercising, and so on can probably help, but there is always the possibility that the cancer will recur. Some of this disease is purely genetic; good diet and attitude may make no difference. So I’m confused about where to stand between accepting impermanence and having the hope and desire to live until my old age, which may help my recovery.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: I see no conflict at all between accepting impermanence and also wanting to live as long as you can. After my own experiences of near-fatal illnesses, it is exactly where I find myself. However, I have one feeling of caution as I read your letter. It is the possibility that if you were to have a recurrence, even after following all the best medical advice available, you might blame yourself “because you didn’t have the right attitude.” Please don’t set yourself up for a guilt trip.

An encounter with impermanence can make one acutely aware, for the first time, of one’s own mortality, and this can be terrifying. As Master Mumon said in one of his commentaries, “You’d better pay attention to what I am saying, or when it comes time for the five elements to separate, you’ll be like a crab in a pot, scrabbling with all eight arms and legs to get out.”

The great teacher Nagarjuna said, “In this world of birth and death, seeing into impermanence is bodhicitta, the mind of awakening.” It can turn one’s mind toward practice, as it did for me. I became focused on the question, “How do you live if you know you’re going to die?” In my search, I was introduced to Zen practice and met Suzuki Roshi. He seemed to me to know what I needed to know, and I began to practice with great enthusiasm, like a drowning person grabbing a life preserver. So my experience of a critical illness actually gave me the gift of practice.

Twenty years later, I had a heart attack. As I stepped into the sunlight after leaving the hospital, I had the thought, “Wow! I’m alive! I could be dead. The rest of my life is just a free gift! Oh, wow, it’s always been a gift. Too bad I didn’t notice it before.” The overwhelming and continuing sense of gratitude that has resulted from that realization has never left me.

The one thing I’ve learned in this life that I want to give to others is this gratitude for everything, including the gift of this precious human life. I hope you will enjoy your gift of life for as long as it is given to you.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: Open awareness is our natural state of mind, which allows all positive qualities to be experienced and expressed in life. When facing challenges such as living with a life-threatening illness, openness can be easily obscured by our fears as well as our hopes. Even when using the word “openness,” we need to observe whether we are creating expectations only to become disappointed when those expectations are not fulfilled. That is expectation, not openness. With openness, whatever the outcome, we are fine. Openness creates a dynamic other than hope and fear.

We become familiar with the power of openness through reflecting upon impermanence and death. This is part of dharma practice throughout one’s life and not only when one is sick or dying. The moment one is born is the moment to realize impermanence is true.

In the West, impermanence often has a negative association. While the initial reflection on the truth of impermanence or the inevitability of one’s death might be unpleasant or even shocking, deeper exploration leads to the freedom to live life fully in the present moment. If you become sad or depressed while reflecting on impermanence, look closer at your experience. You’ll discover it is your attachment that causes you to suffer. Once you recognize that attachment, notice how you experience it in your body, your emotions, and in your mind. You may notice tensions in your body, restrictions in your breathing, or agitation in your mind. Through gentle physical exercise, skillful pranic breathing exercises, and mindfulness-awareness practices, you can release those negative habits.

We are often more familiar with our tensions, sadness, and negative thoughts; we need to release them and become more familiar with open awareness. As you experience more clarity and openness in your body, breath, and mind, rest in the space that has become clearer. Bring clear attention to that opening. In that openness you can discover peace and freedom. That openness is the source of limitless positive qualities. This discovery is the real purpose of impermanence practice. Each one of us can realize: “Yes, it is true, I am dying. Not only am I dying, but thousands are dying at this very moment.” Death is not personal. It is not a failure. It happens to all living beings. Acceptance is important, and that is why a daily prayer in Buddhist liturgy concludes with the line: “Bless me to understand impermanence deeply.”

Once we understand and accept the truth of impermanence, the power of that acceptance supports us to continuously expose hidden fears and attachments and release the restrictions of those hopes and fears, allowing each of us to live fully and well in this moment, whatever the conditions of the moment present. Genes are also conditions and are not primordially true. Don’t limit your experience by thinking that your condition is genetically determined and that’s it. Release that view into openness.

If you are modifying your diet, don’t think, “I have cancer and I might die, so I need to eat this food.” Instead, allow what you eat to nourish you as you live fully and well in this moment.

At the very moment you discover anxiety or fear, release it through the support of your dharma practice. Each moment you release tension and anxiety or abandon negative thoughts, you can experience a glimpse of open space in you. Recognizing and resting in the space that has become clearer, you develop increasing familiarity with the openness of your natural mind and cut the habit of hope and fear that binds all living beings in suffering. This open awareness is the best medicine for living and for dying.

Narayan Helen Liebenson: We all live with the fact of impermanence, whether or not we have a life-threatening disease. When we are very ill, however, we may be able to see more clearly and directly how utterly unpredictable life truly is and the inevitability that each of us will die in some way, at some time. Dharma practice helps us to work with this insight.

But it’s not just a question of seeing impermanence more clearly; we need to develop a wise relationship with impermanence in our daily lives. A wise relationship includes the development of sadha, meaning trust or confidence. In this case, it is the confidence that whatever the conditions may be, we will be able to respond with intelligence and kindness.

Just as in metta (loving-kindness) practice, we wish good health for ourselves and others because it is a blessing in life. At the same time, we are aware that things are the way they are. Thus we bring loving-kindness and equanimity together. A line in a T.S. Eliot poem expresses this well: “Teach me how to care and not to care.” We take care of the body as best as we can, without the belief that we have any ultimate say over nature. We can be aware of the fragility of the body and still have freedom of mind. This is the cultivation of wisdom and compassion.

It may be a popular New Age belief to think that we can “conquer” illness through attitude alone, but a dharmic perspective is that our attitudes don’t determine the outcome. Dharma has to do with suffering and the release from suffering, not the effort to control the uncontrollable. I see this kind of New Age belief leading to double suffering—the suffering of the body plus the suffering that is experienced because “if one just had a better attitude, this would not be happening.” This inevitably leads to a feeling of personal failure when the body doesn’t co-operate with one’s agendas and instead follows the laws of nature.

It is said that the Buddha was neither pessimistic nor optimistic; he was a realist. The Buddha taught the middle path. Hope and desire are on one side; resignation and depression are on the other. The middle path is one of awareness and understanding.

Accepting impermanence is a key to happiness. As the Buddha taught, “All conditioned things are impermanent. Their nature is to arise and pass away. To be in harmony with this truth brings true happiness.”

Valuing your life, living in the here and now, and knowing the point of things—this is a wise attitude. This awareness teaches us not to take so much for granted, and not taking things for granted is the birth of true love.

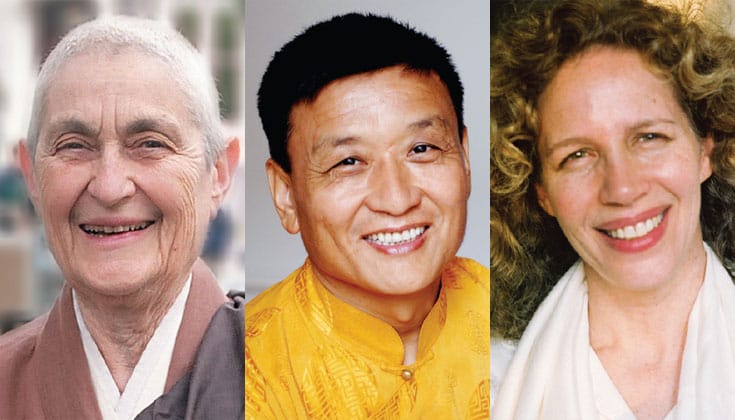

Zenkei Blanche Hartman is former abbess of the San Fransico Zen Center.

Geshe Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche is a lineage holder of the Bön Dzogchen tradition of Tibet.

Narayan Helen Liebenson is a guiding teacher at Cambridge Insight Meditation Center.