The teaching on the twelve links of dependent origination is common to all Buddhist traditions; however, the interpretation of the twelve links, their processes, and particularly the explanation of the first link, ignorance, is different for the Madhyamaka school than it is for the other philosophical schools.

The other schools define fundamental ignorance as grasping at the self-existence of the person. Grasping at the self-existence of a person means believing there is a self that is somehow distinct from our body and mind—our aggregates. Such a self is thought to act like a master over the physical and mental components of a person.

The seventh-century Indian Buddhist philosopher Dharmakirti gives an example of this belief in his Exposition of Valid Cognition (Pramanavarttika): Say an old person whose body is deteriorating and is full of aches is given the opportunity to exchange his body for a much healthier body. From the depths of his mind would emerge a ready willingness to take part in such an exchange. This suggests that deep down, we believe in a self that is distinct from our body, yet somehow master over it.

Similarly, if a person with a poor memory or some other mental deficiency were given an opportunity to exchange his or her mind for a fresh one with superior cognitive powers, again from the depth of the heart would arise a real willingness to enter into the transaction. This suggests that not only in relation to our body but also in relation to our mental faculties, we believe in a self who would benefit from such an exchange, a self that it is somehow the ruler or master of the body and mind.

The other schools define grasping at self-existence as the belief in this kind of discrete self—a self-sufficient and substantially real master that is in charge of the servant body-and-mind. For them, the negation of that kind of self is the full meaning of selflessness, or no-self. When we search for such a self by investigating whether it is separate from the psychophysical aggregates or identical to them, we discover that no such self exists. The other schools’ interpretation of the twelve links of dependent origination therefore defines fundamental ignorance as grasping at such a self-sufficient and substantially real self.

Madhyamikas would agree that gaining insight into such a selflessness does open the way to reversing the cycle. However, as Nagarjuna argues, while this is a form of grasping at selfhood, it does not get at the subtlest meaning of selflessness.

With insight into this grosser type of selflessness, you can reverse some habits related to the grosser afflictions. But wherever there is grasping at an intrinsic existence of the aggregates—the body and mind— there will always be a danger of grasping at a self or “I” based on those aggregates. As Nagarjuna writes in his Precious Garland (Ratnavali):

As long as there is grasping at the aggregates,

there is grasping at self;

when there is grasping at self there is karma,

and from it comes birth.

Nagarjuna argues that just as grasping at the intrinsic existence of the person or self is fundamental ignorance, grasping at the intrinsic existence of the aggregates is also grasping at self-existence. Madhyamikas therefore distinguish two kinds of emptiness—the lack of any self that is separate from the aggregates, which they call the emptiness of self, and the lack of intrinsic existence of the aggregates themselves—and by extension all phenomena—which they call the emptiness of phenomena. Realizing the first kind of emptiness, Nagarjuna and his followers argue, may temporarily suppress manifest afflictions, but it can never eradicate the subtle grasping at the true existence of things. To understand the meaning of the first link, fundamental ignorance, in its subtlest sense, we must identify and understand it as grasping at the intrinsic existence of all phenomena—including the aggregates, sense spheres, and all external objects—and not merely our sense of “I.”

The Relative I

The search for the nature of the self, the “I” that naturally does not desire suffering and naturally wishes to attain happiness, may have begun, in India, around three thousand years ago, if not earlier. Throughout human history people have empirically observed that certain types of strong, powerful emotions—such as hatred and extreme attachment—create problems. Hatred, in fact, arises out of attachment—attachment, for example, to family members, community, or self. Extreme attachment creates anger or hatred when these things are threatened. Anger then leads to all kinds of conflict and battles. Some human beings have stepped back, observed, and inquired into the role of these emotions, their function, their value, and their effects.

We can discuss powerful emotions such as attachment or anger in and of themselves, but these cannot actually be comprehended in isolation from their being experienced by an individual. There is no conceiving an emotion except as an experience of some being. In fact, we cannot even separate the objects of attachment, anger, or hatred from the individual who conceives of them as such because the characterization does not reside in the object. One person’s friend is another person’s enemy. So when we speak of these emotions, and particularly their objects, we cannot make objective determinations independent of relationships.

Just as we can speak of someone being a mother, a daughter, or a spouse only in relation to another person, likewise the objects of attachment or anger are only desirable or hateful in relation to the perceiver who is experiencing attachment or anger. All of these—mother and daughter, enemy and friend—are relative terms. The point is that emotions need a frame of reference, an “I” or self that experiences them, before we can understand the dynamics of these emotions.

A reflective person will then ask, What exactly is the nature of the individual, the self? And once raised, this question leads to another: Where is this self? Where could it exist?

We take for granted terms like east, west, north, and south, but if we examine carefully, we see these again are relative terms that have meaning only in relation to something else. Often, that point of reference turns out to be wherever you are. One could argue, in fact, that in the Buddhist worldview, the center of cyclic existence is basically where you are. Thus, in a certain sense, you are the center of the universe!

Not only that, but for each person, we ourselves are the most precious thing, and we are constantly engaged in ensuring the well-being of this most precious thing. In one sense, our business on earth is to take care of that precious inner core. In any case, this is how we tend to relate to the world and others. We create a universe with ourselves in the center, and from this point of reference, we relate to the rest of the world. With this understanding, it becomes more crucial to ask what that self is. What exactly is it?

Buddhists speak of samsara and nirvana—cyclic existence and its transcendence. The former, as we have seen, can be defined as ignorance of the ultimate nature of reality and the latter as insight into the ultimate nature of reality, or knowledge of it. So long as we remain ignorant of the ultimate nature of reality, we are in samsara. Once we gain insight into the ultimate nature of reality, we move toward nirvana, or the transcendence of unenlightened existence. They are differentiated on the basis of knowledge. But here again, we cannot speak of knowledge without speaking of an individual who has or does not have knowledge. We come back again to the question of the self. What exactly is its nature?

This type of inquiry predates the Buddha. Such questioning was already prevalent in India before the Buddha arrived. Until he taught, the dominant belief was that since everyone has an innate sense of selfhood, a natural instinctive notion of “I am,” there must be some enduring thing that is the real self. Since the physical and mental faculties that constitute our existence are transient—they change, age, and then one day cease—they cannot be the true self. Were they the real self, then our intuition of an enduring self that is somehow independent but also a master of our body and mind would have to be false. Thus, before the Buddha, the concept of the self as independent and separate from the physical and the mental faculties, was commonly accepted.

Innate grasping of selfhood is reinforced by this kind of philosophical reflection. These Indian philosophers maintained that the self did not undergo a process of change. We say, “when I was young, I was like this,” and “when I am older, I will do this,” and these philosophers asserted that these statements presume the presence of an unchanging entity that constitutes our identity throughout the different stages of our life.

These thinkers also maintained that since highly advanced meditators could recall their past lives, this supported their position that the self takes rebirth, moving from one life to the next. They maintained that this true self was unchanging and eternal and, somehow, independent of the physical and the mental aggregates. That was largely the consensus before the Buddha.

The Buddha argued against this position. Not only is our intuition of an inborn self a delusion, he said, the philosophical tenets that strengthen and reinforce such a belief are a source of all kinds of false views. The Buddhist sutras therefore refer to the belief in selfhood itself as the mind of the deceiver Mara—the embodiment of delusion—and as the source of all problems. The Buddha rejected the idea of a self that is somehow independent of the body and mind.

Does that mean that the person does not, in any sense whatsoever, exist at all? Buddha responded that the person does indeed exist, but only in relation to the physical and mental aggregates and in dependence on them. Thus the existence of the individual is accepted only as a dependent entity and not as an independent, absolute reality.

Buddhist philosophical schools therefore all agree that an independent self, separate from the body and mind, cannot be found. However, when we say “I do this” or “I do that,” what exactly is the true referent of the person? What exactly is the person then? Diverse opinions arose among the Buddhist schools regarding the exact identification of the nature of this dependent person. Given their shared acceptance of existence across lifetimes, all Buddhist philosophical schools rule out the continuum of the body as constituting the continuity of the person. Therefore, the differences of opinion surround the way that the continuum of consciousness could be the basis for locating the person or the individual.

In a passage in his Precious Garland, Nagarjuna dissects the concept of a person and its identity by explaining that a person is not the earth element, water element, fire element, wind element, space, or consciousness. And apart from these, he asks, what else could a person be? To this he responds that a person exists as the convergence of these six constituents. The term “convergence” is the crucial word, as it suggests the interaction of the constituents in mutual interdependence.

How do we understand the concept of dependence? It is helpful to reflect on a statement by Chandrakirti in his commentary on Nagarjuna’s Fundamental Stanzas on the Middle Way, where the following explicit explanation of how to understand a buddha in terms of dependent origination is found. He writes, “What is it then? We posit the tathagata in dependence upon the aggregates, for it cannot be asserted to be either identical with or separate from the aggregates.” His point is that if we search for the essence of something believing we can pinpoint some real thing—something objectively real from its own side that exists as a valid referent of the term or concept—then we will fail to find anything at all.

Time and the Self

In our day-to-day interactions, we often speak of time. We all take for granted the reality of time. Were we to search for what exactly time is, we could do so in two ways. One is to search with the belief that we should be able to find something objectively real that we can define as time. But we immediately run into a problem. We find that time can only be understood on the basis of something else, in relation to a particular phenomenon or event. The other way to search is in a relative framework, not presuming an objectively real entity.

Take, for example, the present moment. If we search for the present moment believing that we should be able to find a unique entity in the temporal process, an objective “present,” we won’t find anything. As we dissect the temporal process, we instead discover that events are either past or yet to occur; we find only the past and future. Nothing is truly present because the very process of searching for it is itself a temporal process, which means that it is necessarily always at a remove from now.

If, on the other hand, we search for the present within the relative framework of everyday convention, we can maintain the concept of the present. We can say “this present year,” for example, within the broader context of many years. Within the framework of twelve months, we can speak of “the present month.” Similarly, within that month, we can speak of “the present week,” and so on, and in this relative context we can maintain coherently the notion of a present moment. But if we search for a real present that is present intrinsically, we cannot find it.

In just the same way, we can ascertain the existence of a person within the conventional, relative framework without needing to search for some kind of objective, intrinsically real person that is the self. We can maintain our commonsense notion of the person or individual in relation to the physical and the mental faculties that comprise our particular existence.

Because of this, in Nagarjuna’s text we find references to things and events or phenomena existing only as labels, or within the framework of language and designation. Of the two possible modes of existence—objectively real existence and nominal existence—objectively real existence is untenable, as we have seen. Hence we can only speak of a self conventionally or nominally—in the framework of language and consensual reality. In brief, all phenomena exist merely in dependence upon their name, through the power of worldly convention. Since they do not exist objectively, phenomena are referred to in the texts as “mere terms,” “mere conceptual constructs,” and “mere conventions.”

Searching For the Self

At the beginning of his eighteenth chapter, Nagarjuna writes:

If self were the aggregates,

it would have arising and disintegration;

if it were different from the aggregates,

it would not have the characteristics of the aggregates.

If we are searching for an essential self that is objectively and intrinsically real, we must determine whether such a self is identical to the aggregates or is something separate from them. If the self were identical to the aggregates, then, like the aggregates, the self would be subject to arising and disintegrating. If the body undergoes surgery or injury, for example, the self would also be cut or harmed. If, on the other hand, the self were totally independent of the aggregates, we could not explain any changes in the self based on changes in the aggregates, such as when an individual is first young and then old, first sick and then healthy.

Nagarjuna also is saying that if the self and the aggregates were entirely distinct, then we could not account for the arising of grasping at the notion of self on the basis of the aggregates. For instance, if our body were threatened, we would not experience strong grasping at self as a result. The body by nature is an impermanent phenomenon, always changing, while our notion of the self is that it is somehow changeless, and we would never confuse the two if they were indeed separate.

Thus, neither outside the aggregates nor within the aggregates can we find any tangible or real thing at all that we can call the self. Nagarjuna then writes:

If the self itself does not exist, how can there be “mine”?

“Mine” is a characteristic of the self, for the thought “I am” immediately gives rise to the thought “mine.” The grasping at “mine” is a form of grasping at selfhood because “mine” grasps at objects related to the self. It is a variation on the egoistic view, which sees everything in relation to an intrinsically existent “I.” In fact, if we examine the way we perceive the world around us, we cannot speak of good and bad, or samsara and nirvana, without thinking from the perspective of an “I.” We cannot speak of anything at all. Once the self becomes untenable, then our whole understanding of a world based on distinguishing self from others, “mine” from not mine, falls apart. Therefore, Nagarjuna writes:

Since self and mine are pacified,

one does not grasp at “I” and “mine.”

Because the self and the mine cease, the grasping at them also does not arise. This resonates with a passage in Aryadeva’s Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle Way in which he says that when you no longer see a self in relation to an object, then the root of cyclic existence will come to an end.

One who does not grasp at “I” and “mine,”

that one too does not exist,

for the one who does not grasp

at “I” and “mine” does not perceive him.

In other words, the yogi who has brought an end to grasping at “I” and “mine” is not intrinsically real. If you believe in the intrinsic reality of such a yogi, then you also grasp at selfhood. What appears to the mind of the person who has ascertained the absence of self and its properties is only the absence of all conceptual elaborations. Just as grasping at me and mine must cease, so must grasping at a yogi who has ended such grasping. Both are devoid of intrinsic existence.

The point is that our understanding of emptiness should not remain partial, such that we negate the intrinsic existence of some things but not of others. We need to develop a profound understanding of emptiness so that our perception of the lack of intrinsic existence encompasses the entire spectrum of reality and becomes totally free of any conceptual elaboration whatsoever. The understanding is one of mere absence, a simple negation of intrinsic existence.

Dismantling the Causes of Cyclic Existence

Nagarjuna continues,

When thoughts of “I” and “mine” are extinguished

with respect to the inner and the outer,

the process of appropriation ceases;

this having ceased, birth ceases.

This refers to the twelve links of dependent origination. “Inner” and “outer” here can be understood as the conception of self as either among the aggregates or apart from them. When grasping at self and “mine” ceases, then, because no more karmic potentials related to external or internal phenomena are activated, the ninth link in the twelve links of dependent origination—grasping, or appropriation—will not occur. We will no longer grasp at objects of enjoyment and turn away from things we deem unattractive. Thus, although we may continue to possess karmic potentials, they are no longer activated by craving and grasping, and when this happens, birth in cyclic existence, the eleventh link, can no longer occur. This is the sense in which birth will come to an end.

Therefore, as we deepen our understanding of emptiness, the potency of our karma to propel rebirth in cyclic existence is undermined. When we realize emptiness directly, as it is stated in Exposition of Valid Cognition, “For he who sees the truth, no projecting exists.” In other words, once we gain a direct realization of emptiness, we no longer accumulate karma to propel rebirth in cyclic existence. As we gradually deepen our direct realization, so that it permeates our entire experience and destroys the afflictions, we eventually eliminate the root of grasping at intrinsic existence altogether and the continuity of rebirth in cyclic existence is cut. This is true freedom, or liberation, where we no longer create new karma through ignorance, where no conditions exist to activate past karma, and where the afflictions have been destroyed at their root.

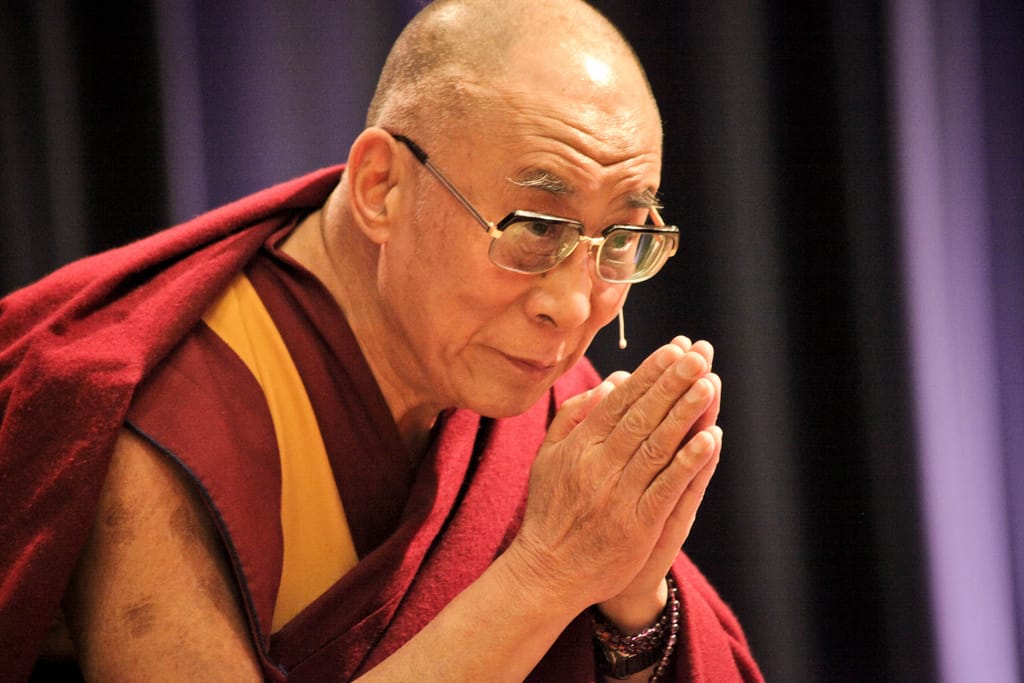

From The Middle Way: Faith Grounded in Reason, by the Dalai Lama, and translated by Thupten Jinpa. ©2009 Reprinted with permission from Wisdom Publications.