Zen is the Japanese name of a Buddhist school that originated in China and spread through East Asia. In China, it is called Chan; in Vietnam, it is Thiền; and in Korea, it is called Seon or Sŏn. Because the school was first spread in the West by Japanese teachers, the Japanese name Zen is what the entire tradition is generally called in English.

All of these names are transcriptions of the Sanskrit dhyana, meaning “meditative absorption.” This reflects the tradition’s focus on meditation practice.

Origins of Zen

Zen’s origin story, which is possibly more myth than history, is that it was founded in China by a monk from India named Bodhidharma, about 500 CE. During the Tang Dynasty, 618–907 CE, some meditation masters who considered Bodhidharma their spiritual ancestor adopted the name Chan for their communities, and eventually, it became the name of a larger tradition.

In China there were initially several sub-schools or “houses” of Zen, but by the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) there were just two, called Linji and Caodong. These two schools differed more in style than in doctrine.

The first Zen temples on the Korean peninsula were built in the 9th century. Today the Jogye order of Korean Zen is the largest school of Buddhism in Korea. It’s believed Zen was introduced to Vietnam as early as the 6th century. Today’s Vietnamese Zen, however, is mostly the legacy of Chinese Linji masters who came to Vietnam in the 17th century.

Zen first reached Japan late in the 12th century. Today there are three schools of Japanese Zen. One is Rinzai, which developed from the Chinese Linji tradition. Another is Soto, which was based on Caodong. The third school was founded by Chinese Linji teachers who came to Japan in the 17th century. The 17th-century Japanese Rinzai establishment wouldn’t accept the Chinese Linji teachers as part of their school, so it became a separate Zen school called Obaku.

Zen in the West

A Rinzai Zen teacher named Soyen Shaku (1800-1919) attended the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. He was the abbot of a prominent temple in Kamakura and was the first Zen master known to visit North America.

While in Chicago, the abbot recommended one of his students for a job with Paul Carus, managing editor of Open Court Publishing. So it was that a young Japanese scholar named Daisetsu Teitarō Suzuki – better known as D.T. Suzuki – came to live in Paul Carus’s house in LaSalle, Illinois. For eleven years, Suzuki translated Asian sacred texts into English for Carus, and he sometimes ran the printing press.

After Suzuki returned to Japan in 1909, he and his American wife, Beatrice Lane Suzuki, began publishing an English language journal, The Eastern Buddhist. In the 1920s and 1930s, Suzuki published books of essays in English about Zen that gained wide circulation in Europe as well as North America. He occasionally traveled outside Japan to give lectures. It was largely through D.T. Suzuki that the West became aware of Zen.

In the 1920s, Soto Zen temples were founded in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and the territory of Hawaii, serving the growing Japanese communities there. At about the same time a Rinzai Zen monk in Los Angeles named Nyogen Senzaki was teaching Zen to not-Japanese Westerners. By the 1930s, a Rinzai Zen teacher named Sokei-an Sasaki was teaching a small group of students in his New York City apartment. Meanwhile, a Chicago matron named Ruth Fuller met D.T. Suzuki while touring Japan and was persuaded to attend meditation retreats at a Zen temple in Kyoto. After her experience in Japan, she sought out Sokei-an Sasaki in New York and began supporting his work. Fuller and Sasaki married shortly before his death in 1945.

The Beats and Zen

Beat was a social and literary movement that began in the 1950s. Prominent writers of the Beat movement, such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen, developed a serious interest in Zen, and in Buddhism generally. Kerouac’s Dharma Bums (1958), a novel with a Zen Buddhist protagonist, was widely read on college campuses. Through the Beats, Zen was introduced into Western popular culture. The Beats found a kindred spirit in the English writer Alan Watts, author of The Way of Zen (1957).

Zen’s literary success inspired some young Americans to visit the Soto temples in San Francisco and Los Angeles. They also flocked to the new Zen Studies Society established in New York in 1956. The Soto temples eventually founded separate Zen centers for English-speaking practitioners. These were the San Francisco Zen Center, founded in 1962 by Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, author of the classic Zen Mind Beginner’s Mind, and the Zen Center of Los Angeles, founded by Taizan Maezumi Roshi in 1967. At the same time, other Zen teachers began teaching outside Japan, and the first Western students authorized to teach were founding their own Zen centers.

Vietnamese Zen was introduced to the West by Thich Nhat Hanh (1923–2022), whose Plum Village tradition is headquartered in southwest France. The Korean Kwan Um School is an international organization founded in 1983 by Seung Sahn (1927–2004). The head temple of Kwan Um is in Cumberland, Rhode Island. Chinese Chan is represented around the world by the international Dharma Drum Mountain organization, founded by Chan master Sheng-yen (1931–2009).

Zen Teachings, Zen Practice

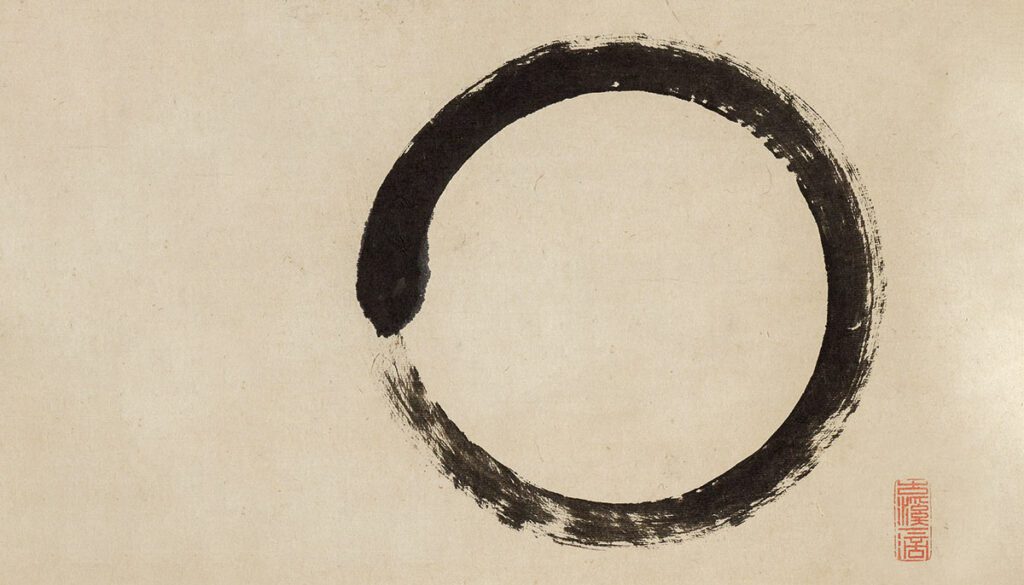

Zen is most distinguished from other schools by its emphasis on intimate, intuitive insight over intellectual understanding. New Zen students are taught zazen, not lectured on doctrine. As students’ skills in meditative absorption deepen, teachers guide them toward the realization of teachings by various means, such as koan contemplation.

A distinguishing teaching of Zen is “sudden enlightenment,” which means that enlightenment is already present in all beings and must only be realized and actualized, not acquired. Zen places great importance on the realization of Madhyamaka (Middle Way) teachings such as sunyata (“emptiness”) and on understanding the nature of the mind.

The primary means of realization is zazen. In Zen monasteries, life centers around zazen, but it extends into all activities, making work, eating, sleeping, and even mundane tasks like going to the toilet forms of “moving Zen.”

Koans

Koans are brief stories or anecdotes, often involving exchanges between Zen master and student, that present some facet of dharma, the teachings. But they do so in ways that do not make intellectual sense. People sometimes assume koans are riddles, but the resolution of a koan is not a clever answer but a change in how the practitioner perceives reality.

Koans were first collected and published during the Song Dynasty. The oldest is the Biyan lu, or Blue Cliff Record, completed in 1125. In the traditional collections, the brief koan or “case” is accompanied by pointers, commentaries, capping verses, and footnotes. And Zen teachers do make up new koans sometimes.

The practice of working with koans in meditation began in 11th-century China. A Rinzai master named Dahui Zonggao (1089–1163) introduced the practice of contemplating a huatou, a short phrase or sometimes just one word that represents the crux of the koan. “Contemplating” does not mean thinking about what the huatou means. Rather, the huatou is taken into the body, breath, and bones and allowed to do its work.

In China, most practitioners will sit with the same huatou for years. The Rinzai Zen school developed a koan curriculum in which students are assigned a koan by their teacher and present their understanding to the teacher. When the teacher approves a student’s understanding, a new koan is assigned.

Although koan contemplation is considered a primary practice of the Linji or Rinzai schools, the koan literature belongs to Caodong and Soto Zen as well. Some of the collections were compiled by Caodong teachers. In Soto, koans are presented in dharma talks and in commentaries.

Dharma Transmission

Zen has a strong tradition of “face-to-face transmission” from teacher to student. This direct transmission is the means by which Zen had maintained institutional integrity through the centuries.

Dharma transmission is formalized in a ceremony in which a Zen teacher formally recognizes that a student is worthy of being a lineage holder and teacher. Most Zen teachers will tell you that nothing is “transmitted,” however. Transmission is more a matter of a teacher recognizing that the student has already realized and clarified the dharma and is ready to begin guiding others.

The transmission tradition led to the creation of lineage charts that show the unbroken transmission of dharma, from teachers to students, that goes back to the historical Buddha and the Buddhas before Buddha. The tradition of Zen lineage charts probably began late in the 7th century, however.

Related Reading

What Is Zen Buddhism and How Do You Practice It?

Zen teacher Norman Fischer takes you through the principles and practices of the major schools of Zen. Includes specially selected articles for further reading.

Dogen, the Man Who Redefined Zen

From just sitting to cooking as practice, Dogen defined how most of us understand Zen today. Steven Heine on the life and global impact of Dogen Zenji.

There Is No Teacher of Zen

It’s a paradox, says Hokuto Daniel Diffin. No one can teach you Zen, but you need a teacher to understand that.

Zen Mind, Vajra Mind

The late Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche described Suzuki Roshi as his “accidental father” in America, and through their close friendship he gained great respect for the Zen tradition. In this talk, Chögyam Trungpa looks at the basic differences between Zen and tantra.

Buddhism A–Z

Explore essential Buddhist terms, concepts, and traditions.