About a year after I finished the traditional three-year retreat program and had begun my work as a dharma teacher, I experienced a kind of breakdown, a severe sense of being stuck and uninspired. I reached out to my dharma teachers, mentors, and other spiritual guides, and it quickly became clear that my identity as a lama and resident teacher had somehow choked my identity as a queer Black man. I was privileging the lama over Rod.

Rod was the person I had earned the right to be; Rod had gone through years of working directly with self-hate, depression, and low self-esteem to emerge fierce, fabulous, edgy, and beautiful. Meeting the dharma had furthered my personal and interpersonal transformation, but now I was trying to fit into the mold of being a lama, a role largely informed by tradition and by other people’s expectations of me. To heal, I needed to bring Rod back into center and place him in dialogue with Lama Rod. This approach drastically shifted my teaching style and my role as a teacher; when I regrounded myself in my many identities, I came to embrace that I was teaching from a place of intersectionality.

“Intersectionality” speaks to the reality that we are influenced by any number of identities, all of which are informed further still by our social and political locations. We are not just white or Black or gay or transgender. We are an expression of a community of identities and influences that may not be apparent to those around us—or even to us.

In my experience, authenticity as a dharma teacher requires a kind of radical presence. “Radical” speaks to a sense of remembering and returning to a simple and basic way of being in the world, one that reduces the violence to oneself and others; it honors one’s own passions and aspirations and relates to the world from a place of equanimity. When we choose this way of being in the world, we feel at home in our own body, with no desire to leave it; because we feel at home in the body, we feel at home in the world. That is radical presence. And at its heart is an awareness of one’s own intersectionality.

What we teachers fear most is letting others see that we are not as confident as our years of dharma practice may suggest. Teaching from our recognized intersectionality helps us practice vulnerability as an expression of dharma. It lets others see us in ways that can be healing, and it gives us permission to let go of our masks.

In my daily practice and as I am preparing to offer a dharma talk, I often do a practice of naming my different identity locations and then reflecting on them. (I like the term “location” because it brings awareness to the fact that I have been grounded in certain identities and that I do not move out of them—I firmly occupy them. I have been put in these places; I am conditioned to remain in these places.)

Practice grants us the space to allow this identity shifting to happen and to call that shifting our home.

When you sit down on the cushion, try to name for yourself the identities that most impact how you show up. In my case, I am a Black, polyqueer, able-bodied, cisgender male lama who is of mixed class and radically minded. This seems like a lot. But if we are really in tune with our various identity locations, we will all similarly find a great deal of complexity. And these identities are always shifting. Practice grants us the space to allow this shifting to happen and to call that shifting our home.

It has taken years for me to openly acknowledge my own complexity. I do this not to develop more attachment to identity but to understand what it means to be constantly interacting from the intersections of these identities. If there is some awareness, then I am more likely to recognize how my view of the world is skewed by the perceptions that accompany these identities.

I identify as Black to recognize that I have been raised within an Afrodiasporic community as a descendant of African enslaved people. Black is an expression of the socially constructed racial group, with one of its features being a brown skin tone. While I am ethnically Black, I am also politically Black, which means I identify as Black as a strategy to resist a culture of white supremacy and as a way of standing in solidarity with other marginalized and oppressed people.

Poly is a way to identify that I am not currently choosing to be in monogamous relationships but am exploring different kinds of sexual and intimate relationships with multiple partners; queer refers to my identification not just as a gay person but also, politically, as a person whose attraction to other bodies is not limited to other cisgender males.

Able-bodied is a challenging term, as it sets up a duality in which there are bodies that are capable and thus better than bodies that are less capable and therefore seemingly lesser. I want to be transparent about challenging language and identifications that reproduce domination and subordination. What I struggle to articulate with this identity location is that though I am a larger-bodied person, this is not a hindrance to accessing most spaces; physical spaces and the activities that happen in these spaces have been designed so that bodies like mine are privileged.

Cisgender means that the gender of male that I was assigned at birth is also the gender I feel is most authentic for me.

Mixed class helps me understand that though I have been economically poor most of my life and have been emotionally affected by this, I have still had exposure to resources that have disrupted the material consequences of poverty: scholarships and free health care, as well as support from family, friends, and students that helps me travel, pursue dharma study, and secure things like a car or laptop.

Radical means that I am committed to both challenging power structures that perpetuate violence and imagining what my life and my communities could look like if we addressed systems of hierarchy and power imbalances.

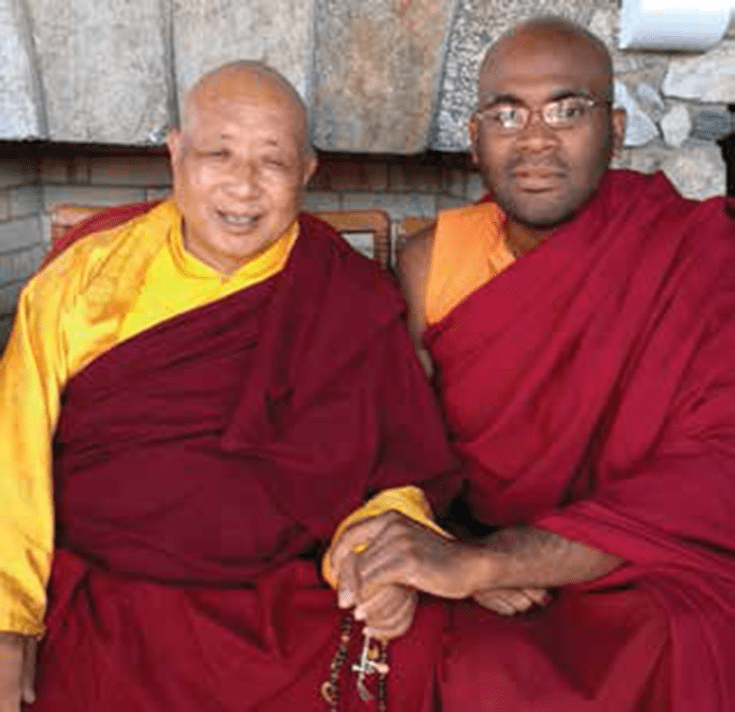

Finally, I am a lama—an authorized dharma teacher in the Tibetan tradition of Buddhism. Lamaism is itself a complex identity with its own history and customs, a spiritual and cultural identity emerging from Tibetan religion and culture. It is a location of great honor signifying some spiritual attainment and entrustment with the authority of one’s lineage. I am deeply grateful for this opportunity to benefit beings. However, lamaism is directly influenced by patriarchy and other forms of domination; currently, it is being assimilated by many white initiates integrating their own unexamined white supremacy and privilege. It has thrived not just through the spiritual attainment of its initiates

but also by a fixed power structure that is, for the most part, unchallenged—the results, too often, have been gross ethical violations of student/teacher and sangha/teacher relationships. This identity location, as someone committed to radical thought and social change, is the one I struggle with the most.

I have been conditioned through my disprivileged identities to constantly justify why I should be alive and taking up space.

These identities are part of a shifting dialogue between privilege and disprivilege; though I have the advantages that come with identifying as a cis-gender male lama, many of my other identities are marginalized. In my practice, I have struggled to transcend both social and internal labels: oppressed, flawed, wrong, ugly, poor, a burden, a problem.

I have come to see that I live within a social, political, and economic environment that was not created to privilege me or to even care about me outside of my capability to produce products and wealth for others. This understanding has been a source of strength. To put this another way, I have been conditioned through my disprivileged identities to constantly justify why I should be alive and taking up space.

Of my many identity locations, I experience Blackness most strongly. It is a site of profound transhistorical and intergenerational trauma. Much of my struggle to work with oppression is rooted in race, yet at the same time, this site is one of profound resilience, hope, and love. I have noticed how easy verbal communication is for me, especially in front of groups. This, I feel, comes from a love of verbal communication in the Black community originating in the homeland tribal communities in Africa. My community’s language expression is rooted in playfulness and the expression of intimacy. Call it “talking shit,” “cracking,” or if you are older, “playing the dozens”; it is how we are heard and seen. It is how we train to love and value our individual voices and the recognition that our individual voice is part of a community voice. It was how we have long practiced being free. Within a white supremacist culture that holds Black speech in contempt, our practice has been one of resisting total devaluing and silence. When I am “talking shit” from the cushion, I am doing much more than idly talking—I am resisting and interrogating the psychic violence of white supremacist silencing. I am practicing freedom.

To teach from a place of intersectionality begins with understanding that teaching is not an objective activity. We are offering dharma teaching from the many ways in which privileged and disprivileged identity locations inform who we teach and even what we teach. Most white teachers will not consider race in the dharma because white teachers have been conditioned not to see race and to normalize their racialization. It is the same for male teachers who do not openly talk about patriarchy.

For many white teachers, connecting to an identity of whiteness that has been perpetuated and defined by the domination of other races is a significant obstacle. Whiteness does not mean oppression, but still, it has often been defined by superiority and the power over other.

To resist naming our identity locations is to commit a kind of aggression toward ourselves and to further obscure blind spots that hurt others. Others are hurt when they are not seen; invisibility is another form of violence and oppression.

Often, teachers claim that the way they experience a certain dharma is how others should experience it. However, teaching from a place of intersectionality requires us to be conscious of the ways in which we center our story lines. Having your own story line is not a bad thing. However, if we do not know how we are relating to our narrative, we begin to normalize it; this makes others in the room who do not identify with our particular story invisible—further trauma for those who are already marginalized. If your experiences do not match up with the teacher’s experience, you may feel your practice is inadequate.

In seeing our own intersectionality, we can become sensitive to how other people intersect with us.

We can start to counteract this tendency by simply asking questions at the start of a dharma talk: Who is new to the group? What is your practice? What do you expect to get out of the session? We don’t need to ask directly about identity locations, but we can choose to acknowledge that there are other bodies in the room with their own stories and desires.

Awareness of intersectionality also helps me see how I exert power as a teacher—or where others are exerting power over me. In seeing our own intersectionality, we can become sensitive to how other people intersect with us.

The Heart Sutra tells us that form is emptiness and emptiness is form; if that’s true, then our practice is to try to recognize the integration of form and emptiness, and to let ourselves sit in the utter discomfort of that. From this discomfort emerges a greater capacity to hold space for contradictions. Ultimately, we are not these identities, which is awesome. But relatively, we are, and that’s awesome too! Privileging one over the other is not the practice here. The practice is to bridge the relative truth of I am with the ultimate truth of I am not, to hold them together while exploring the tendency to want to bury ourselves in one extreme. This practice can be deeply unsettling, but if we can hold the ultimate truth together with our relative truth, then space opens up within our identity locations, and we can recognize them without being firmly planted. For example, for me to identify as Black is to first recognize what it has meant to be conditioned as a Black body; at the same time, I see that ultimately I am not Black but still conditioned to perform and to relate to the Black cultural conditioning.

Much like Dorothy confronting the illusion of the Wiz of Oz, we too must muster our courage to show our true faces; we must reveal our social faces before we hope to reveal our ultimate faces.

The great bodhisattva James Baldwin once wrote: “I am what time, circumstances, history, have made of me, certainly, but I am also much more than that. So are we all.” Teaching from intersectionality is really about the courage to be vulnerable and real on the spot, to embrace what time and history and various causes and conditions have shaped us to be. Only when we acknowledge both the forces that have shaped us as well as our unique identities molded through that shaping can we move through into the realization that we are much more than our intersectional identity. The most powerful dharma teachings I have heard have been from teachers who allow themselves to be glimpsed by others, who go to the emotional edge that we are all too often trying to avoid. I suspect people want to see me in a certain way, as a well-put together product of years of intense practice; however, my role as a teacher is to show the sangha how I struggle to make the teachings relevant and applicable to my life. Much like Dorothy confronting the illusion of the Wiz of Oz (or Wizard, if that’s what your intersectionality calls for), we too must muster our courage to show our true faces; we must reveal our social faces before we hope to reveal our ultimate faces. Teaching from a place of intersectionality is first being radically present—to ourselves, to others, and to the world.