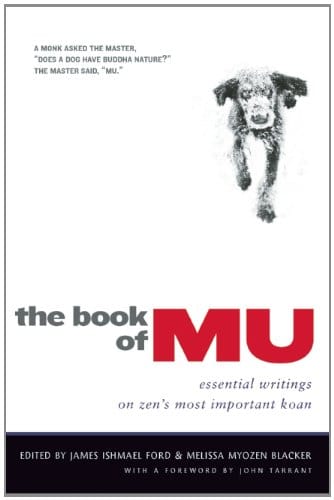

The Book of Mu: Essential Writings on Zen’s Most Important Koan

Edited by James Ford and Melissa Blacker

Wisdom Publications, 2011

$17.95; 366 pages

Koans, the spiritual riddles extracted from Zen masters’ tales about enlightenment in classical China, lie at the heart of Rinzai tradition practice today, especially in its centers in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan, but also in the West. Of the hundreds of koans studied during Rinzai training, the most prominent is the Mu koan, in which Chinese master Zhaozhou (Joshu) responds, “Mu” (literally, “No”) to a monk’s query, “Does the dog have buddhanature?” The Mu koan is the first case recorded in the frequently cited Gateless Gate collection from the thirteenth century, and it is usually the introductory koan for training disciples. In Korean Zen, it is sometimes the only case, but presented in multiple variations to check the progress of a trainee’s degree of understanding.

The Book of Mu is a collection of about forty brief commentaries, both classical and modern, on the Mu koan from Asian and Western sources. This is the third book in a series on seminal ideas in Zen theory and practice—following The Art of Sitting and Sitting With Koans—and although the essays are at times repetitive in referring back to the Gateless Gate’s interpretation, they collectively do a very thorough job of highlighting the significance of the Mu koan in Zen Buddhism today.

In modern Zen practice, disciples are asked to present their own interpretation of Mu. In a fascinating scene in “Land of the Disappearing Buddha,” a segment on Japanese Buddhism in the still-popular Long Search series on world religions produced by the BBC in the seventies, the bemused British narrator observes a Zen master and a student during a dokusan, or private interview. The young trainee seems to connect when he responds to the koan by roaring the word “Mu.” But Yamada Mumon, then the famous roshi at Daitokuji, one of the major Rinzai temples in Kyoto, calmly dismisses him with a comment to the effect that the answer must come from deep within and not be pronounced by the lips alone. The master then rings the bell, signalling that the time is up and that he’s ready to interview the next student waiting in line.

Even though in the film it seemed like the disciple was screaming not just “Mu,” but “Muuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu” (using “u” eighteen times for emphasis as suggested in the essay “Give Yourself Away to Mu” by Gerry Shishin Wick), he nevertheless failed to communicate an appropriate form of expression reflecting an authentic understanding of Zen. Because Mu represents an all-encompassing spiritual experience that must be lived in each moment, it cannot be acquired in any conventional sense but it also should not be considered an object of study, as is pointed out by nearly all the contributors to this volume.

“After thirty years of American Soto Zen practice, I finally caught up with Mu on a trip to Japan—or maybe Mu finally caught up with me,” Grace Schireson explains in “Becoming Mu.” As Jan Chozen Bays writes in “Always at Home,” we must be “able to let go and let Mu work on us. This happens when Mu penetrates every breath, every footstep, every blink, every touch, every sound. Raindrops falling—Mu, Mu, Mu. Crows calling—Mu, Mu, Mu. Hands pick up Mu and spoon Mu into Mu.”

The Book of Mu is divided into four parts. The introductory section provides historical background as well as Robert Aitken’s translation of The Gateless Gate’s prose and poetic commentary. This is followed by translations of Dahui, the Chinese master who first advocated the “head-word” (Ch. huatou, Jp. watō, Kr. hwadu) method of concentrating on Mu without intellect; Dogen, the founder of Soto Zen in Japan, who commented extensively on the case; and Hakuin, the leader of Rinzai Zen in the Edo period, who devised a system for studying koans still used today. The third section consists of commentaries by “founding teachers in the West,” all prominent figures who represent lineages and training traditions originating in Japan, China, Korea, and Vietnam. The final part, which comprises nearly two-thirds of the book, presents essays by contemporary Western teachers as well as two from Japanese Zen masters. Although most of the remarks refer to The Gateless Gate’s exegesis, there is consistently fresh material that illuminates the practice of sitting with the Mu koan.

One of the highlights for me is John Tarrant’s “No. Nay. Never. Nyet. Iie,” which outlines “Strategies for working with the koan.” Its six strategies are: finding the koan by eliminating distractions; seeing that any part of the case contains the whole; accepting your various mental states; relaxing or not trying too hard to solve the koan; minding your own business by staying focused on the case; and timing, or remaining patient while the process of working with the case gradually unfolds. This discussion is rather brief, and I wish the author had fleshed out the typology and sequence in more detail.

I found the essays that make comparisons with Western literature and thought particularly intriguing. Joan Sutherland’s “Unromancing No” cites a poem by Neruda on the importance of maintaining silence while concentrating on nothingness, which is a way that the word Mu is sometimes translated in East Asian Buddhist and Daoist philosophy. Susan Murphy, in “A Thousand Miles the Same Mood,” discusses a Celtic fairy tale about a girl who keeps watch over an apparently dead body which comes to life as a result of her attention, as well as a comment by Rilke on the need for maintaining a courageous attitude in the face of inexplicable experiences. In John Ishmael Ford’s “On the Utter, Complete, Total Ordinariness of Mu,” there is an interesting mention of the mystical Gospel of Thomas, in which Jesus highlights the role of a concrete object such as a stone or piece of wood in enabling concentration. The essay concludes with an improvised poem that begins, “It is just this pebble. / It is just this breath. / It is just this Mu…”

The historical section of this book is useful, but there is one basic drawback: it pays too much attention to one particular version of the koan while overlooking another important version from the classical period. Although the introduction does mention briefly the other main version of the case, in which there are both Mu and U (“Yes”) responses with a fuller dialogue for each (it is also referred to in Tarrant’s foreword), this rendition is not analyzed in any depth. In general, the Soto approach to interpreting the Mu-U version of the koan—initially used by Dogen’s ancestor in China, Hongzhi, who was a contemporary of Dahui’s and compiler of the collection of cases that became The Book of Serenity—receives relatively little attention. Since the double-answer version has been included in many traditional Chinese and Japanese Zen collections used by both the Rinzai and Soto schools, its history and text should neither be excluded from the discussion nor be seen in a polarized, sectarian way. For most of its history, the double-answer version was cited almost as frequently as the one-answer version that has become so much better known today.

In the classical period there were also many variations on the meaning of the Mu koan. Even before Dahui and Hongzhi were referring to the case, the record of Yuanwu’s teacher Wuzu in the eleventh century contains the remark, “The master ascended the hall and said: ‘Does a dog have the buddhanature or not? Still, it is a hundred thousand times better than a cat.’ He stepped down.” A verse from this period by a monk named Fo Yinyuan conveys an inconclusiveness which relativizes our understanding of the Mu koan, “The great function of total activity expresses freedom. / Yes and no are two parts of a pair. / How much karmic consciousness comes into people and dogs? / Henceforth we shall always remember Zhaozhou for commenting on this.” A verse by Benxue Yi reads, “The dog has buddhanature / The dog does not have buddhanature / Always walking toward both ends. / One arrowhead cannot be used to reach two targets, / And even with its karmic consciousness deriving from the past, it is only a dog.”

The approach to the nonduality of “yes” and “no”—or positive and negative—responses to the question about the dog’s buddhanature expressed in these verses from the classical period is at once in accord with and yet contradictory to many of the interpretations contained in this book, which is focused exclusively on negation.

Of course, no single volume can be expected to cover all the possible topics related to the main theme, and this after all is The Book of Mu rather than “The Book of Mu and U.” The book will be sure to inspire many Zen students and practitioners to seek out their own unique appropriations of the koan from among the multitude of responses currently available as well as those which are yet to come. As the editors write persuasively, “All of these many works about this one word are pointers toward your own intimate relationship to the koan Mu, to your own buddhanature. The sincere young monk and the venerable teacher Zhaozhou are alive in you right now, ready to accompany you on this journey of discovery. They truly are, after all, you yourself.”