Hongzhi was a twelfth-century Zen master in China who had a great influence on Dogen. The following is one of his practice instructions—it’s something we are to do:

Emptiness is without characteristics. Illumination has no emotional afflictions. With piercing, quietly profound radiance, it mysteriously eliminates all disgrace. Thus one can know oneself; thus the self is completed. We all have the clear, wondrously bright field from the beginning. Many lifetimes of misunderstanding come only from distrust, hindrance, and screens of confusion that we create in a scenario of isolation. With boundless wisdom journey beyond this, forgetting accomplishments. Straightforwardly abandon stratagems and take on responsibility. Having turned yourself around, accepting your situation, if you set foot on the path, spiritual energy will marvelously transport you. Contact phenomena with total sincerity, not a single atom of dust outside yourself.

—from Cultivating the Empty Field, translation by Taigen Dan Leighton with Yi Wu

I’ve often said that if I could meet Hongzhi, I would probably ask him to read me his poetry while I lie on my back and watch the clouds. Maezumi Roshi wrote this about him: “The tongueless one prescribes with wordless sparklings, a medicine of nondual existence for the bodiless one. When we appreciate the effect of this medicine, we know that medicine, we know that Master Hongzhi’s 834-year-old relics are still fresh and warm and vitally universal.” And I might add, they are here with us today.

We come together and collect our hearts and our minds, ceremoniously. Caerimonia, the Latin root of ceremony, means “with reverence, with sacredness, with healing.” So we collectively gather together our griefs, our joys, our sorrows, our broken trusts—in reverence, in sacredness—to restore and make whole what’s never been apart.

We can and do divide just about anything. But we know from experience that we can close the divide. We’ve all had moments when we release the thinking, discursive mind, and just chant, just eat, just walk, and just be. We yearn to return to this natural space, experiencing a universe that is undivided and nondual. Perhaps, because we know that’s our nature, that is what we are continuously seeking.

Wholeheartedness is sometimes used as one way of expressing virya, or energy, as joyful effort. I recall when looking over the seven factors of enlightenment, the phrase “joyful effort” gave me something, a little zing. I then found this quote by Thanissaro Bhikkhu: “The path doesn’t save all its pleasures for the end. You can enjoy it now.” I was so happy to hear that! Here we are, involved in the harvesting of the heart, or as Dogen would say, our body–mind, and we can enjoy that.

Illumination has no emotional afflictions.

The emotional body is a wonderful way to enter into anything and everything that needs to be seen. Some of us, growing up, may have been told we were too emotional. When my mother would say this to me, I would get even more upset. If she said those words today, I’d say back, very lovingly, “Thank you. It’s true.” Let’s not pretend.

When we are no longer defining self on the level of emotion, our sense of self is liberated from our conflicted feelings. But we cannot get to this point by bypassing our emotions. We cannot avoid what we feel.

When we come to a practice such as this, we can sit down with our emotions and feel them without holding on. Being awake on the level of emotion means no longer deriving a solid sense of self from how and what we feel. Usually our sense of self is enmeshed in what we feel. We say to ourselves, “I feel angry. I am angry!” Looking deeply into this, we can see that what we are really saying in that moment is my sense of self is fused with my anger. If we look even more deeply, we see we actually cannot be defined by an emotion that runs through the body. The fusion is an illusion.

Seeing this is awakening through the heart. We discover what we feel, period—and what we feel doesn’t need to be avoided, nor does it define us. The more we shut out the body and our feelings, the more we retreat to thinking, which tends toward disembodying. The intensity of our compulsive thinking is in direct proportion to the extent to which we are not willing to experience our emotional body and therefore disassociate from it.

When we are no longer defining self on the level of emotion, our sense of self is liberated from our conflicted feelings. But we cannot get to this point by bypassing our emotions in the hopes of arriving at some exalted state. We cannot avoid what we feel.

Emptiness is without characteristics. Illumination has no emotional afflictions. With piercing, quietly profound radiance, it mysteriously eliminates all disgrace.

My understanding of how Dogen sees this is that it’s like relying on what is concrete in our life—which cannot be relied on, except in relation to that which is like empty space. In other words, “Form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form.” Undivided.

Our emotions and feelings are fantastic pointers, directly revealing the heart and what is unresolved in our being. For a long time, it can be hard to accept our “piercing, quietly profound radiance” revealing what is unresolved; we may not have the patience. For a while, I wanted to see this self as a completely resolved being. We all know how painful that can be—pretending to have it all together, while inside we are trembling with fear of being detected as a hot mess. We don’t want that to be seen, even by ourselves. Yet that’s really where it needs to happen.

Eventually, what’s not serving us will either implode or explode—sometimes both. Just like when nature needs to come into accord with cause and effect, a natural balance will come. We can try our darndest to hold it all together, but eventually we learn that we’re able to respond in other ways.

Many lifetimes of misunderstanding come only from distrust, hindrance, and screens of confusion that we create in a scenario of isolation.

We are so used to being divided that there is almost a fear of being undivided, of being complete, even though that’s what we yearn for. So we end up grasping at a solid sense of self, hoping to maintain some security. After all, what’s on the other side? We don’t know. We hear that all the time—“don’t know”—but it’s a real thing! When we let go, it means we are leaping into the unknown. We won’t know ourselves in the ways we did before. Yet this offers an inkling of what we might call the liberated state. This is the revolution the Buddha taught: no longer defining ourselves through what we feel, our sense of self is liberated from conflicted emotions.

Our bodies are great truth meters. I can’t lie very well—my mother could take one look at me and say, “You are not telling me the truth!” I was saying one thing, but my body and my complexion were saying something else. As soon as we go into emotional states like hate, jealousy, blame, greed, envy, we are perceiving from a state of division. So those emotions can serve as flags reminding us that we are not seeing the true nature of things.

Having turned yourself around, accepting your situation, if you set foot on the path, spiritual energy will marvelously transport you. Contact phenomena with total sincerity.

Emotional turmoil tells us we have an unconscious belief that isn’t true. This is good news, because if we can hang in there without shutting down, it will be revealed. That’s the hard work, but it means that if we see it, we are no longer unconscious. We can make the effort to inquire further and ask, “What am I believing about myself right now?” Be curious; remember that joyful effort is the energy we have to wonder, to question, to awaken completely.

Curiosity is a way to study the self and also to forget the self. We might notice, “Oh, I am hating this person. I am hating this situation right now. Fascinating, fascinating.” Or we might say to ourselves, “This powerful feeling, it’s not me. Yet I so believe it is. I so believe it is.” Maybe we can turn the light around into not hating this illusion and seeing that this too is the “wondrously bright field from the beginning.” In this way, we enter the realm of possibility. Exploring what is possible in the moment is something very different from believing; again, we have to not know.

I heard a story that demonstrates the power of our beliefs. A little boy said to his mother, “Mom, pretend you are surrounded by hungry tigers, all wanting to devour you. What would you do?” She said, “Oh! I would be terrified. I wouldn’t know what to do. What would you do?” And the little boy replied, “I’d stop pretending.”

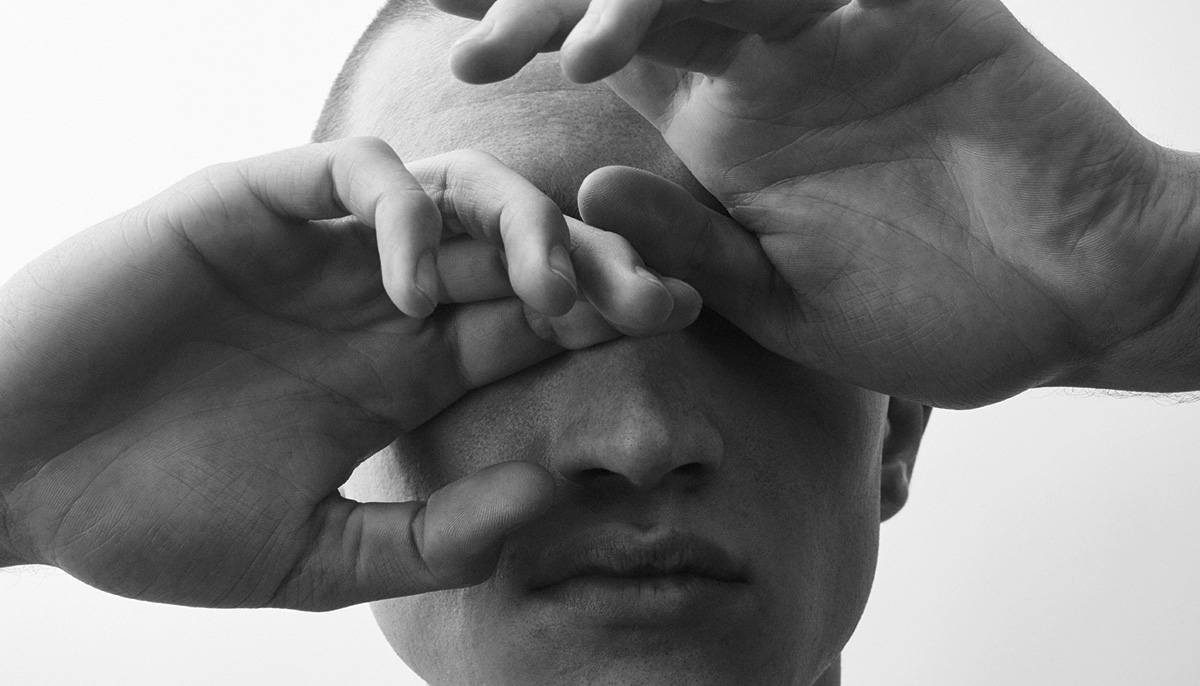

We can’t awaken from the neck up.

The emotional body is an entry point into any illusion, any belief, anything that can cause a sense of separation. Zazen is the practice of coming back down to earth. And coming down to earth is not easy; we don’t always arrive intact. We’ve been living in our heads for a long time, perhaps lifetimes. And now we are being called from every direction to reinhabit the bodies we’ve left behind. The whole body comes along; we can’t awaken from the neck up. We must awaken the whole body–mind. As Dogen tells us, when we see forms and hear sounds with the whole body and mind, unreservedly, we will understand. When we do that, we will remember who we are.

These days, we are inundated with the constant flow of information. I once read that when you order a single cup of coffee, maybe an “organic decaf vanilla latte extra hot,” you make more decisions than your grandparents made in a week. Ponder the levels of connection that our brains and hearts are trying to digest. In one month, many of us are connected with more people online and in person than our ancestors were in their entire lifetimes. No wonder we are overwhelmed. We can be knocked off emotional balance so very easily, then walk around unaware.

In zazen we are coming down to the earth, literally, to be able to get up. “By whose authority,” Mara asked the Buddha, “do you take this seat of awakening?” We also say this to ourselves, right? This is our conversation with Mara. The Buddha reached down, touched the earth, and said, “This is my witness.”

We are here. We are embodied. Rest open; allow the earth to bring stability and support. Then let that stability move up to the mind, to relax and release, to awaken from the heart. Awaken from the very bottom of the spine, extending downward to the earth and upward to the sky, and boundless in all directions.

Straightforwardly abandon stratagems and take on responsibility.

The Buddha asked us to look at what we crave. This is the second noble truth. We look at our cravings, habits, and patterns so that we can know them and see how they take us away from the natural unfolding of our life. The Buddha said, “When we begin to crave, we become ignorant.” We are always organically unfolding, in relationship with everything and everyone. But we have forgotten this interrelationship, this interdependence. We are not flowing with what is being put into our lives.

We meet many fears: fear of the unknown, of loss, of humiliation, of inadequacy. In trying to eliminate our fears, we commit to staying controlled by them. Hongzhi says, “Contact phenomena with total sincerity.” Generate faith, confidence, courage, enthusiasm, perseverance to see for yourself and to see yourself. As soon as we say, “It shouldn’t be like this; it shouldn’t have happened,” we experience that internal division. It’s immediate. We fight with what’s here, what is. We don’t like it, or we love it and we want it to stay. As soon as there is something in us that judges, craves, or says it shouldn’t be, we feel the division. When we argue with what is, we never win. Worse still, we might be arguing with what happened twenty years ago. And a lot of what we are arguing with, if we take a closer look, isn’t even based on what is true.

When we feel into our emotions, though, we may not always find ourselves divided. We’ve all experienced this, too. We can feel sadness and grief without being divided. We can even cry our eyes out or feel a certain amount of anger without being divided. In that moment when we are not dividing, when we just let it be, a measure of joy comes through—we don’t make it happen; it simply arrives. Our virtues soar: we feel patient, curious, generous, and experience gratitude and a sense of connectedness in the knowledge that we are living the wholehearted way.

Thus one can know oneself; thus the self is completed. Having turned yourself around, accepting your situation, if you set foot on the path, spiritual energy will marvelously transport you.

This is why we continue—because of this marvelous spiritual energy that comes from seeing something clearly. True inquiry is experiential. It’s not trying to stop us from having unpleasant feelings, or to stop something from happening. It has no goal other than itself.

Here’s another story: Mahasattva Fu, a brilliant scholar in China, was lecturing one day on the Parinirvana Sutra. People came from a great distance to listen to him. In the middle of his talk, a Zen monk started laughing hysterically. Can you imagine? He’s giving this serious lecture, and a monk just starts laughing. Fu quickly finished his lecture, went back to his quarters, and asked his attendant to bring the monk in for tea.

When the monk came in, Fu said, “I’ve studied these sutras for the last twenty years, and I trained with the great masters here in China. What is it that you saw? What did I say that was wrong?”

The Zen monk said, “You didn’t say anything wrong. What you said was absolutely true, but it’s all talk. It’s so obvious you don’t know the thing itself. You don’t see the thing itself.”

And Fu, this wonderful man, said, “What can I do so I can experience the thing itself?”

The monk told him, “You should stay in your quarters and sit zazen. If you do that for ten days, I bet you will see what I am pointing to. Abandon your thoughts. Have no discriminations. Just see into your inner world.”

Fu did that. He told his attendant not to bother him, and he went into his room and sat zazen. After several days, while sitting late at night, he heard a flute playing in the courtyard.

“Ah!” He ran over to where the Zen monk was staying and knocked on the door.

The monk said, “Who is it?”

Fu replied, “It’s me.”

The monk asked, “Well, who are you?”

Fu said, “I am myself!”

To which the monk responded, “What kind of drunk are you, carousing around here late at night? Go back to bed!” And he slammed the door.

Fu returned to his room, where he wrote a poem:

In those days I remember

when I had as yet no satori,

each time I heard the flute played, my heart grieved.

Now I have no idle dream over my pillow.

I just let the player play whatever tune he likes.

What I love about this story is Fu’s surrender and readiness to experience even more deeply. All of us should remember: yes, perhaps we’ve had a glimpse, but it’s just the beginning. The awakened heart loves the world as it is, not just as it could be. The more we awaken at the heart level, the more we awaken to one of our deepest callings: to just love.

Hongzhi, speaking from the point of view of the awakened heart–mind, offers us this:

Directly arriving here, you will be able to recognize the mind ground dharma field that is the root source of the ten thousand forms germinating with unwithered fertility. These flowers and leaves are the whole world. So we are told that a single seed is an uncultivated field. Do not weed out the new shoot, and the self will flower.

Our sadness, our loneliness, our fear, and our anxiety are not mistakes. They are not obstacles to our path. They are the path. The freedom we long for is not found in the eradication of these but rather in the information they carry. We need not transcend anything here but instead be willing to become more deeply intimate with our lived, embodied experience. Nothing is missing. Nothing is out of place. Nothing needs to be sent away.