Introduction by David Chadwick.

The teacher was ready; the students came. Without a plan, Shunryu Suzuki arrived in San Francisco on May 23, 1959. The Zen garden of America had been fertilized by Nyogen Senzaki, Paul Reps, D.T. Suzuki, the Beats, Alan Watts, and the First Zen Institute of America in New York. Instant satori and the inscrutable orient were on people’s minds. Suzuki emphasized that practice is enlightenment. “I sit zazen at 5:30 in the morning. You are welcome to join me,” he’d say. He took one step after another, and was always there with and for his students, aware of the fragility of the situation. Three years later, almost to the day, he was installed as abbot of the Japanese American Sokoji Buddhist Church. In August his wife and younger son arrived, and articles of incorporation were filed for The Zen Center of San Francisco. Fifty years ago, he had decided to stay.

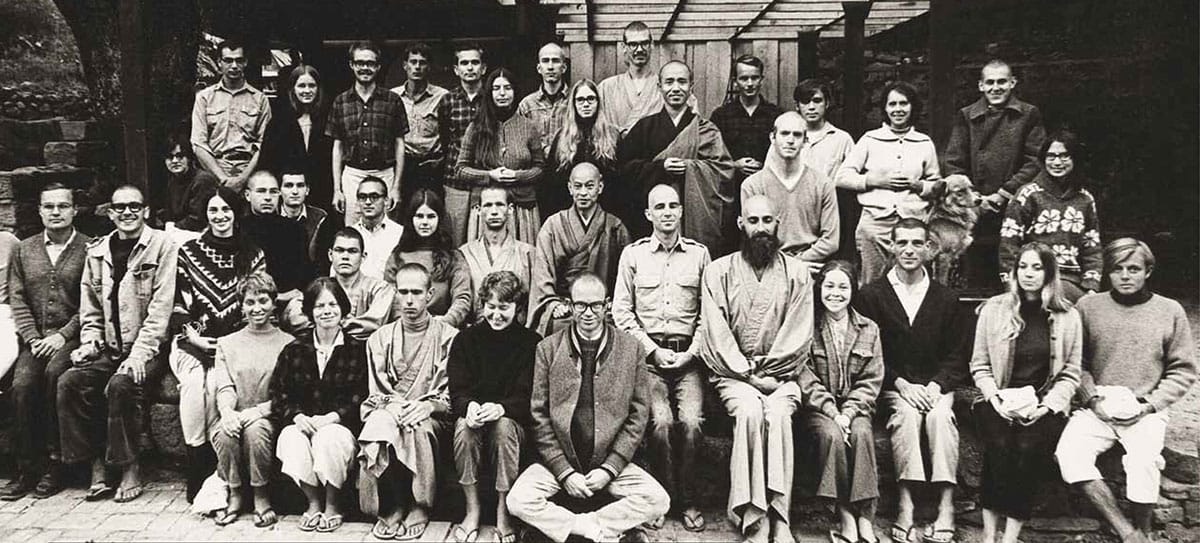

Fueled by a growing interest in Asian ways and the hippie migration, the zazen group expanded and founded the Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, a pioneering Zen monastery at Tassajara Springs in Los Padres National Forest. Women and men practiced there together, following Japanese forms in a new way and chanting in both languages. The retreat center also opened the gates to the public for the summer guest season, which kept the community grounded in society, brought in much-needed revenue, and exposed thousands to the practice of Zen.

In 1969 Suzuki and his assistant, Katagiri, left Sokoji, in a mutual agreement with the board of the Japanese-American congregation, and moved to the new City Center on Page Street. Residential practice expanded there, and positions and options increased. There were priest and lay ordinations, but “We’re neither priest nor lay,” Suzuki said. He expressed concern about the growing size of Zen Center; some elders lamented a loss of intimacy.

After Suzuki’s death from cancer in December of 1971, his sole American heir, Richard Baker, became abbot. Green Gulch Farm was acquired, adding a third site to the San Francisco Zen Center, the official name that was adopted in 1995. The center also started several businesses, including a grocery store, bakery, and restaurant, which provided financial support to the organization and opportunities for work practice. Outreach to the neighborhood and society increased, as did the emphasis on scholarship.

Baker’s well-publicized departure in 1983 was like an unsettling divorce in the community and was followed by reflection, downsizing, and a decentralizing of teaching and administrative authority. There was a shift from a single lineage holder in the position of leadership to multiple abbots with term limits, as well as a new emphasis on training more teachers, some of whom went on to start other centers.

Suzuki’s and his students’ spirit of acceptance and tolerance has always been a key part of San Francisco Zen Center’s story. The hippies came, and Suzuki said, “I am very grateful to them.” That spirit continues today. Women have played a central role from the beginning. Gays and lesbians have found acceptance. The percentage of young people at the centers continues to be greater than at most small zazen groups. Members have always welcomed diversity, though most have been white college-educated people from the middle and upper-middle classes. Students and teachers have been active as therapists and in social work, environmentalism, peace work, harm reduction, hospice care, administering meals to the homeless, and other forms of service and right livelihood. The SFZC has been a hub of culture and art and has created friendly spaces where people and outside organizations can meet.

One of SFZC’s strengths is that it didn’t keep expanding but became the source of a wide-ranging community of independent centers, groups, teachers, and individual practitioners in America and Europe, some close to the mother ship and some not. Add those who share this lineage through the printed word and other media, and the ripples of what began fifty years ago extend far, even washing back up on Asian shores.

Tradition and Modernization

Buddhadharma: On the occasion of San Francisco Zen Center’s fiftieth anniversary, we thought it would help to hear how Zen Center, as one of American Buddhism’s most important and thoughtful institutions, is addressing the important issues that all Buddhist communities face as the dharma makes a true home in the West. The first issue I’d like you to discuss is the tension—one that of course can be very creative—between Buddhist tradition, with its Asian roots, and the values and culture of modern Western society.

Blanche Hartman: At Zen Center there is a dynamic tension between those two things. To me, what is important is that people continually look at it. There are people who ask why we chant all these things in Japanese since we’re not Japanese. We don’t even understand the words. Other people say these forms are very important, and we should continue to look at our resistance to doing them in a traditional way. To me, the particular balance is not so important. The important thing is continually looking at it.

Norman Fischer: The lure of Zen Center was always that Suzuki Roshi carried this very tension within himself. He was faithful to Soto tradition—he wore his robes, he transmitted the rituals very carefully, and when he didn’t know the rituals, he brought in Japanese experts to help us. He was conservative in that sense, but at the same time he wanted Zen Center to be independent of the Japanese Soto establishment. He wanted Zen Center to find its own way, and he was attentive to the needs of Western students. This is why, I think, he turned Zen Center over to an American as his successor. He had Japanese priests who were very good, whom he could have turned to, but he chose an American.

So the tension between the traditional and the modern, the East and the West, was there from the beginning. Zen Center is very conservative, and yet very open and non-conservative at the same time.

Blanche Hartman: Suzuki Roshi always kept zazen at the center of his focus. There were many unusual things that he did—for example, letting men and women practice together from the get-go—but zazen was his anchor point, and he gave his fullest attention to those people who came to sit with him every day. It happened that the first few were women, because he spoke at a class where several women were interested in learning more about Zen. So he said, well, I sit every day and if you want to come sit with me, you can. Zazen was always the focus.

Steve Stücky: I was sitting in New York with another Japanese teacher when I heard that Suzuki Roshi had died. This was December of 1971, and I found out that he had named an American as his successor. In 1971 that was a very interesting situation, so I traveled across the country to San Francisco partly to see how this would work—actually making the shift from a Japanese teacher to an American in charge. I read it as a statement of the tremendous confidence that Suzuki Roshi had placed in the sincerity of American practitioners. For me, that was a breath of fresh air, and I stayed at Zen Center partly because he had this confidence in the sincerity of his American students.

Monastic and Lay Practice

Buddhadharma: There is another creative tension we all deal with between deep practice and study on the one hand, and on the other, making the dharma available to all who would benefit from it by engaging the wider society. At Zen Center, this is reflected in a unique combination of residential monastic training and a diverse lay community.

Mary Morgan: It’s not easy meeting the needs of all these different kinds of practitioners, because there are limited resources. How much energy do we put into our training program for our priests? Isn’t Zen Center really about training teachers for the future? What about all the people who continue to knock on our door and say we want attention and training from the teachers? This is one of those dynamic tensions that doesn’t have an easy resolution. Yet Zen Center continues to respond to all the needs that are presented.

Norman Fischer: Most Zen groups across the country offer retreats, or sesshins, but don’t provide opportunities to live in a monastic practice environment for months or years. There are only a few Zen sanghas that do that, and of those, I think Zen Center has the highest number of people who can do monastic residential practice for one month, six months, five years, ten years, thirty years. This is very difficult to do, and I think Zen Center has done a fantastic job figuring out how to support people for five or ten years or a whole lifetime of practice.

It seems to me this is a unique situation in Zen—life as practice lived in a practice community. It’s not just retreat or deep meditation, but everyday life completely surrounded by zazen. You can’t fully appreciate Zen unless you appreciate that life, and a lot of Zen Center’s efforts and problems and joys have to do with trying to maintain that life of practice in the modern world.

Mary Morgan: To add to Norman’s picture, there are families that have raised their children to adulthood at Green Gulch Farm, and there are families living at City Center. We sometimes invite families to come to Tassajara for threemonth practice periods. And now Zen Center is exploring the development of a senior living community. The impetus is our commitment to housing our monks who are of a certain age and have worked at Zen Center for at least twenty years. So the residential nature of our practice continues to expand.

Having said that, it’s also true that large numbers of people come to City Center and Green Gulch every week to enjoy our public programs. And there are more and more laypeople who want a broader, deeper, richer training program, not just weekly lectures or an occasional class, but an actual training program. So about four years ago Zen Center responded to that request by setting up a yearlong intensive training program for non-residential students, and it has been repeated in various iterations over the last couple of years.

Blanche Hartman: One thing that’s interesting is that nonordained laypeople participate fully in the monastic schedule at Tassajara along with those who have chosen ordination. We go from people who have not taken any vows, to householders who have taken vows as laypeople, to people who have taken ordination as monks. It’s interesting that our monastic practice is not just for the ordained.

Steve Stücky: The core of Zen Center is dedicated, longtime practitioners, whom you’ll find at each of our three centers. Before people become members of the senior staff, we like them to

deepen their practice first. Then when they take on responsibility, they are ready and stabilized, with depth and confidence in their practice that they can offer to other people. Residential practice for a core group of people in leadership is really a key to how Zen Center is able to sustain itself and offer what it has to others. Residential practice is the key training component in our system of rotating people through various leadership positions.

Blanche Hartman: Using the traditional method of training, people have the opportunity to train as a director, treasurer, guest manager, head of the kitchen, head of the zendo, or work leader. Each of these senior staff positions is talked about in Dogen Zenji’s teaching—this goes back to the traditional versus modern question. We just did a mountain seat ceremony for Gaelyn Godwin in Houston, Texas. The last position she held before she left Zen Center was director of the monastery at Tassajara. In the course of their training, every one of the senior staff has had an opportunity to develop their leadership skills in these various traditional roles.

Norman Fischer: The Zen Center training program applies to non-residents and long-standing practitioners as well. Zen Center practice takes in the whole of a person’s life. It’s not just a place where you access and learn something about Buddhism, and then go back home and figure out what to do with it. Even as a non-resident, your whole life is involved. You have relationships with teachers and sangha peers. Everything in your life—your economic life, your psychological life, sometimes your romantic life—everything is involved in your practice. It’s pretty thorough. So when the leaders of Zen Center are considering students’ practice, they’re considering all these things. It’s quite complicated and impressive, when you consider how many people are involved. I think it’s unique not only in the Western world but in Buddhism in general to have this full-life practice and full-life commitment.

Gender and Diversity

Buddhadharma: Buddhism comes here from generally homogeneous, patriarchal, and conservative societies. Zen Center has been and remains a leader in reforming Buddhism to reflect contemporary American values such as gender equality and diversity. What is the history of that effort and what is its focus today?

Blanche Hartman: Suzuki Roshi came here at a time in American history when women were pushing against the assigned roles that they had had for many years. It was a lively topic all over the country, and naturally it came up in Zen Center as well. Suzuki Roshi didn’t personally ordain the first woman student he felt was ready to be ordained because he had never ordained a woman before. He sent her to Japan to study with a woman teacher and be ordained there. But not long after that he actually ordained a woman himself. He was not sure he understood how to train women. But I guess the women who were there let him know that they thought he could—and he did.

I also think there was something conscious about inviting me to be the first woman to take on the abbot seat, even though I happened to be one of the oldest at the time. I don’t think it’s a significant consideration now. The attitude now is, of course a woman can be abbot. For people who have been practicing for a long time, it doesn’t really matter what their gender is; it matters what their practice is.

Steve Stücky: In our morning service liturgy we do the traditional chant of the names of our Chinese and Japanese male Zen ancestors. But people may not realize that Zen Center has also adopted a chant recognizing the women ancestors who have sustained and supported this practice from the time of Shakyamuni Buddha to the present day. We recite a list that begins with some of the nuns named in the Therigatha, the “Verses of the Elder Nuns,” and then continues with female Chinese Chan and Japanese Zen masters. This started when Blanche and Norman were co-abbots in the late 1990s and is completely part of our everyday practice now.

Norman Fischer: As far as I know, there is no policy on the books that there has to be gender parity in the leadership, but I think there is an informal understanding that we want that, and we feel uncomfortable if there’s an imbalance. A while ago, it looked like we might end up with three male abbots, and many men and women alike said, “Whoa! This is not great. We really should have some gender balance.” So even though there’s no formal policy, I think we’re doing really well in terms of gender balance, compared to diversity in general. I think that’s a thornier issue. We’re working on it, but it’s hard to have a diverse population.

Steve Stücky: It is very difficult. I agree with Norman that Zen Center does pretty well on gender balance. We have an informal way of keeping it in mind when we make decisions not just about the abbess seat, but other leadership roles as well, including chair of the board, president, vice-president, and so forth. Another aspect of gender that’s come up is working with the LGBT community. Just last week the diversity committee was discussing how transgendered people should use the baths at Tassajara. We’ve worked with that in various ways, and it’s sometimes hard to reach a comfort level for everyone involved.

We try to directly face the issues that come up with all aspects of diversity. We’ve made specific efforts in our staff trainings to address issues of class and racism. It’s something we’re paying attention to, but we’ve not been able to change the balance within Zen Center much beyond the surrounding social structure and context in which we exist. It will take time, but eventually we’ll have much more of a diverse population racially, and even with class, which is harder to see and more complex to address.

Blanche Hartman:I t’s really a thorny issue, because if we don’t have sufficient numbers of diverse members, then each new person of color who comes in the door doesn’t see a community they feel that they can fit into. They don’t see themselves here. Making this a welcoming place for anyone who comes through the front door is critically important, and something that we’re working on all the time. But it’s difficult: until there is enough presence of people of color, and teachers of color, who are fully engaged and visible within the community, it will be very hard for new people of color to find a home here.

Mary Morgan:We have a diversity committee, and a diversity coordinator creates programs for different marginalized communities and educates our residents and leadership about diversity issues. Still, a lot of people don’t necessarily think about different people’s experiences when they walk into Zen Center. People who are in the majority see people like themselves all around and take that for granted. It takes a conscious effort to ask: what would it be like if I didn’t see myself here? How would that feel? It’s the same with gender parity; it requires a conscious effort all the time. I think if many people in the sangha were not mindful of those issues, we wouldn’t have as many women as we currently have in our leadership. All these diversity or inclusion issues require a deep mindfulness to keep them on the front burner.

Governance and Authority

Buddhadharma: Governance is another challenge as many communities move away from the traditional leadership model, in which authority is focused on the teacher. Zen Center had an extremely painful experience with the departure of Richard Baker, Suzuki Roshi’s chosen successor, and was forced to think deeply about issues of governance, authority, participation, and transparency. What is the model now?

Mary Morgan: I think that’s another ongoing process. For a couple of years we’ve been engaged in a trial effort to shift from having two co-abbots to three abbots. We are experimenting with having an abiding abbot or abbess at City Center—currently that’s Christina Lehnherr—and an abiding abbot or abbess at Green Gulch—currently Linda Cutts. Each abiding abbess focuses primarily on her respective local temple. In addition, we have a central abbot—currently Steve Stückey—whose focus is primarily on Zen Center-wide issues. The abiding abbesses and the central abbot share spiritual authority for the entire organization, but the particular focus of each is slightly different.

It seems like we’re moving toward making that structure permanent. We are a very large, geographically diverse community, with very different activities going on at our three temples. There was a recognition that we needed a more effective and timely decision-making process at each temple and overall for the entire organization. Related to that is increasing our commitment to transparency. What are the responsibilities of each abbot? They should be written down and available to everyone in the sangha. Our website describes our governance polices in detail. There’s an effort to be not only transparent but also accountable.

Steve Stücky: The abbots have a term of office, so it’s not a lifetime appointment. Their names are put forward by an elders’ council, which is a group of about fifteen senior practitioners, and are then brought to the board of directors, which is elected by the sangha, for ratification. That’s how the abbots are selected.

Buddhadharma: The system seems to have a fair number of checks and balances built into it.

Steve Stücky: That’s right, and that has been an evolution at San Francisco Zen Center. We decided to have term limits for abbots. On the question of who should nominate and elect abbots, it was felt the board of directors wasn’t sufficient, because it wouldn’t reflect the confidence of the whole sangha. The elders’ council was specifically created with that primary responsibility in mind.

Buddhadharma: What is the nature of spiritual authority within the Zen Center community?

Mary Morgan: That’s a question many people ask, and people have different pictures of exactly what that is. It’s a matter of continuing conversation.

Blanche Hartman: I think the important thing is sincerity of practice. Are people deeply committed to their vow? And the community makes that decision by who they go to for guidance. One’s sincerity and practice is easily seen by the people who live with you every day.

Norman Fischer: Also, the abbots’ spiritual authority and spiritual interests extend to questions of administration, personnel, finances, and everything else. Even though Zen Center has a president and a board who are looking over those things, the abbots are not uninvolved. It’s not like there’s some big division between administration and the spiritual life. It’s all one thing. That’s one reason why, as Mary was saying, the abbot’s seat has been reorganized. It’s because the agenda of an abbot of Zen Center is really huge. Everything is part of the practice; everything is part of the spiritual life. So spiritual authority is involved in every aspect of Zen Center life.

Steve Stücky: I think spiritual authority has three primary aspects. First is one’s own realization, which comes from deep practice and study of dharma. Second, it comes from one’s teacher, which we formally and publicly recognize through dharma transmission. And the third source of spiritual authority is the sangha, as Blanche was saying. The sangha actually recognizes the faith, dedication, and commitment of a person’s practice. The mountain seat ceremony, in which we install an abbot or abbess, is a kind of an empowerment from the sangha. Without these three, it doesn’t feel that someone has a complete basis for the authority that they’re teaching from, living from, and acting from.

Buddhadharma: Many of you have lived, practiced, and worked together for decades. There are probably no secrets about anybody’s strengths and neuroses. I don’t imagine anybody can pull the wool over people’s eyes to get into a position of authority.

Norman Fischer: That’s a great point, and it’s one of the facts of life of Zen Center that makes it interesting and unique. We do have many people who have practiced together day by day by day, side by side, for decades. And even though the generation of us for whom that’s true is slowly fading away, I think there is a new generation who will have the same experience. That’s a level of engagement, authority, and dharma that doesn’t appear in any of the official documents but is a major part of what Zen Center is about.

Transmission and Succession

Buddhadharma: The issue of transmission and succession is particularly important now as the baby boomers—sort of the founding generation of American Buddhism, who were taught directly by Asian teachers—prepares to hand over the reins to younger people. What does the future look like for Zen Center and the dharma lineage of Suzuki Roshi?

Steve Stücky: I’m excited by the number of people at Zen Center in their twenties and thirties who are really dedicated and beginning to take on leadership. It doesn’t mean that the future is guaranteed, and it doesn’t mean that we don’t have a lot of work to do to support their training, but I do see a number of people I’m really excited about as potential future leaders, teachers, and abbots of San Francisco Zen Center.

Blanche Hartman: Yes, I also see some very promising young people who have a lot of enthusiasm for practice, and I feel confident that this lineage will continue.

Buddhadharma: As I understand it, dharma transmission and the Zen Center training program are how the practitioners, teachers, and leaders of the future are developed.

Blanche Hartman: For me, dharma transmission means someone has clearly taken on the bodhisattva vow as the basis of their life and has sufficient understanding to be able to help others take on that vow.

Norman Fischer: It’s a requirement to be abbot of Zen Center that you are a priest in the lineage with dharma transmission. I think we all agree with Blanche that dharma transmission is not a matter of having a certain kind of experience in meditation or lecturing brilliantly on texts. It has to do with really being solid in your practice and bodhisattva vow. Kindness and the wisdom of practice are the main thing. In the last decade or so, Zen Center also has been giving lay transmission, which we call lay entrustment. We now have a number of lay teachers who are empowered to teach Zen, lead retreats, and have students. The only difference at this point is that lay teachers are not ritually empowered—they can not officiate at services and so on. If they want to pass on precepts to their students or appoint a successor in their personal lineage, they would need a priest to give blessing to whatever rituals are involved.

Blanche Hartman: One of the people who has worked the hardest to complete the formal training of people who have been practicing for years and have given their life to this community is my teacher, Sojun Mel Weitsman, who is also Norman’s and Steve’s teacher. He became the teacher’s teacher. There are two long-standing teachers here who are responsible for the transmission of most of the current teachers at Zen Center, Sojun Mel Weitsman and Tenshin Reb Anderson. But Sojun in particular focused on completing the training of those people who were sort of orphaned after Richard Baker left. Sojun is obviously not the only person who’s given dharma transmission to people, but he gave dharma transmission to a certain generation of people who had been Suzuki Roshi’s strong students and were left to drift when Richard left. We owe a great deal to him for doing that.

Personally, I did not want Richard to leave. I wanted him to understand what had been harmful about his actions, truly repent, and stay and practice with us. But it didn’t seem to be possible for him. I think he has since apologized, but at the time he couldn’t really understand how he had caused harm. I still love him, you know. We would not have survived through the period following Suzuki Roshi’s death without him, and I think he needs that appreciation and recognition.

Norman Fischer: Several years ago we were at a big gathering of Buddhist teachers and there was a panel on training future teachers. When it was Zen Center’s turn to present our training program, we sort of looked at one another and said, “Well…” Because we don’t really have a formal training program. We just live together and practice together and we train in taking different roles, and years go by. Even if it’s not explicit, it’s an effective kind of training program and we have confidence it will produce good dharma leaders in the future. So I think we’re okay on this score. We’re still doing it.

Mary Morgan: Another aspect of our strength going forward is that we are committed to widening our circle in so many different ways. While residential training is core to producing our future teachers, we’re also very aware of the importance of non-residents and their needs. It’s important to remember that there isn’t a wall around Zen Center and the residents who live there. Zen Center is porous. People go in and out. When Steve became co-abbot, he had not lived at Zen Center for a significant period of time. When Christina Lehnherr became abiding abbess at City Center recently, she had not lived inside Zen Center for several years. People go in and out, which is one reason why paying attention to the needs of the wider sangha, as well as to training teachers who are currently in residence, is a mutually beneficial process.

Steve Stücky: That’s an excellent point. We appreciate the value of residential training, and at the same time we know that people benefit from life experience outside of monastic training. I’m involved with several other teachers with the Shogaku Zen Institute, which is a kind of an adjunct to the residential training. It prepares people to take on a pastoral role in a sangha outside of Zen Center—things like understanding psychological issues and modalities, being flexible in how to present the dharma, and specific training in group process and sangha dynamics. We now have about forty official affiliate sanghas, and people are training in their affiliate sanghas and then coming to Zen Center for some of their training. So I think in the future the permeability of the identified edges of San Francisco Zen Center will continue to expand.

Zoketsu Norman Fischer was co-abbot of San Francisco Zen Center from 1995 to 2000 and continues to serve as one of the center’s senior teachers. He is also the founder and spiritual director of the Everyday Zen Foundation, an organization dedicated to adapting Zen teachings to Western culture.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman is a senior teacher at San Francisco Zen Center and was the center’s first female abbot. She was ordained as a Zen priest in 1977 by Richard Baker and received dharma transmission in 1988 from Sojun Mel Weitsman.

Myogen Steve Stücky became co-abbot of San Francisco Zen Center in 2007 and has served as central abbot since 2010, following the restructuring of the abbot leadership. He has been involved with San Francisco Zen Center since 1972.

Mary Morgan has been on the board of San Francisco Zen Center since 2007. She is also the chair of the governance committee and a member of the diversity committee. In 2003 she received lay ordination from Teah Strozer, a dharma heir in Suzuki Roshi’s lineage.