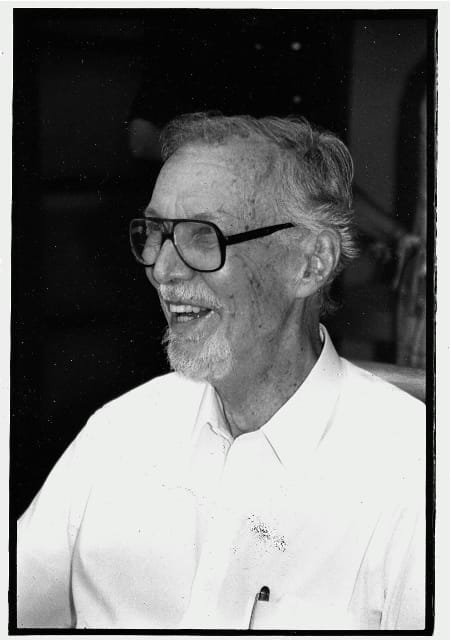

Aitken Roshi was not my formal teacher, but he was my friend and guide and mentor through thirty years of practice. I call him Roshi because the word perfectly expresses both the respect and the affection in which I hold him. Roshi is an honorific Zen title meaning “elder teacher,” and the sound of the word reminds me of Nonie, or Bubbi—someone grandmotherly and kind.

I met Aitken through friends who were his students, and in 1978, I sat a weeklong sesshin with him in Port Townsend, Washington. This was no ordinary sesshin. It was a Zen/Catholic sesshin, organized in connection with some young people Roshi knew and admired from the Catholic Worker House in Seattle, where they served free meals to many people every day. A Catholic priest offered communion to all the sesshin participants, whether they were Catholic or not, as part of our daily schedule, and we chanted psalms as well as sutras.

In that sesshin, Roshi gave lectures not just about traditional Zen teachings but about the teachings of Jesus, Trident missile protests, and a poem by Wallace Stevens as part of the Way of the Buddha. And it was seamless; it was all part of the Way. These were the threads of Roshi’s life and teaching, and this was what made him extraordinary, this joining of rigorous traditional Zen practice, radical work for social justice, and love of literature and art.

It was in that same year that Aitken Roshi, his wife, Anne, and his student Nelson Foster, talking on the porch of the Maui Zendo, founded the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, though I didn’t know about it at the time. And it was the Buddhist Peace Fellowship that would bring me back into contact with Aitken Roshi more than a decade later.

I came to know Roshi in a new way when, in 1990, I became the editor of Turning Wheel, the journal of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship. During my seventeen years there, Roshi wrote articles on a wide variety of topics, including money, right speech, and anarchism.

Scholar that he was, he often sent his articles along with footnotes. I would say, “It’s not really our style to have footnotes. Could we just insert the references into the text?” He would graciously yield, but then he would send me another essay with footnotes. After a few years, when I had more confidence as an editor, I decided, “If Roshi wants footnotes, Roshi gets footnotes.” But he was the only one.

He started an important dialogue in the pages of Turning Wheel on sexual misconduct, speaking clearly about the need for ethical guidelines and calling Zen teachers, both Asian immigrants and Americans, to accountability for their actions. He didn’t name names but he didn’t mince words, either.

In one of his most controversial pieces, he made a radical suggestion: to bring back from the Buddha’s time the drastic practice of “shunning” as a way to deal with Buddhist teachers who sexually abuse their students. I don’t believe any sangha took up his suggestion, but it gave depth and strength to the dialogue. As his editor, I was particularly moved by his honesty about himself. In this same 1995 article, he wrote about how sometimes a young woman would come into the interview room in a low-cut dress, and when she bowed to him, she might partially expose her breasts. “In the early days, I would shut my eyes for the crucial moment, then open them again before she made eye contact… I’m seventy-eight years old now, and the fires are banked, but under the ashes the coals are still glowing.” After submitting the essay to me, Roshi had misgivings about this admission and wanted to take it out, but I persuaded him not to. I was honored that he took me seriously.

He was a crucial support to BPF during the years I worked there. When BPF went through the rocky times that are common for small nonprofits, Roshi would consult with us in conference calls and sometimes visit California.

Roshi’s activism continued to the end. Well into his eighties he stood in the road with young people protesting the war in Iraq, holding up a sign that said, “The System Stinks.” And this was the man who wrote commentaries about the Zen koans of thirteenth-century Chinese Zen Master Wu-men. His respect for the ancestors was woven together with a radical commitment to social change.

When Aitken was seventy-nine, he stepped down as head teacher of the Diamond Sangha, and passed the reins on to his dharma heir, Nelson Foster. I went to the stepping-down ceremony at the Palolo temple on Oahu. The grand occasion included a shosan, in which Roshi sat in a ceremonial chair and visitors asked him questions about the dharma. In the only exchange I still remember, someone asked, “What is the most precious thing?” He replied, “A good night’s sleep.”

I was moved by this intimate and humble answer. Yes, I thought, he must be tired sometimes—he works so hard as a teacher and a writer. I hope he sleeps tonight.

He moved to the Big Island to live near his son, Tom, and for several years he continued to teach, write, go to peace vigils, and agitate for justice. In 2004, as his health was weakening, he and Tom moved back to Honolulu, where he could get the assistance he needed.

The last time I saw him was in 2006, when I went to Honolulu to visit him, and to interview him for a special issue of Turning Wheel honoring him. The day after I arrived, Roshi had to go to the hospital because of a respiratory infection.

In his hospital bed, hooked up to various tubes, he looked back on his life and recalled being a prisoner in an internment camp just outside Kobe, Japan, during World War II. He said that one day he saw American planes bombing the city of Kobe, and the next day he saw Japanese women and old men leaving their bombed-out homes and filing up the trail past the internment camp. “It hit me pretty hard, and I resolved at that point that in addition to making my life one of Zen study, I was going to make it a life of social action.”

“Did you think they would be two separate things?” I asked him.

“No, they couldn’t be, because there was just one me.”

As we talked, Roshi watched with pleasure a pair of sparrows billing and cooing on the balcony outside his window. When a nurse came in to check on him, he introduced me to her and told me about her five children, as if he and the nurse were old friends, though he had just met her.

He was tired, sick, and discouraged to find himself back in the hospital, and yet he continued to take joy in the life around him.

One of my favorite Robert Aitken books is The Dragon Who Never Sleeps, a collection of his gathas, or short verses, for practicing mindfulness in everyday life. His vows drop onto the pages like petals.

Falling asleep at last

I vow with all beings

to enjoy the dark and the silence

and rest in the vast unknown.

Have a good night’s sleep, dear Roshi.