Hearing the Cries of the World

We all experience suffering. Everybody has problems, issues in our lives, pain, not getting what we want, and getting what we don’t want. Underlying all this is a fundamental level of suffering, a feeling of dissatisfaction, hollowness, insecurity, or sadness — at a deeper level, a feeling of incompleteness. This shows up, especially in relation to material things. We try to obtain things to fill that sense of hollowness or dissatisfaction. We may also use power from our position, fame, friends, or family. Whatever we turn to to fill that hollowness and dissatisfaction may help temporarily, but then we become empty again. It is like a bottomless bag. Whatever you put in the bag only fills it temporarily, and then it becomes empty again.

The time of the Covid-19 pandemic was incredibly difficult. There were crises and turbulence all over the world, and the truth of suffering became more evident to most of us. I couldn’t travel due to lockdown restrictions, so I stayed at Tergar Osel Ling Monastery in Kathmandu, Nepal. I started practicing and reading ancient texts, including books on Abhidharma, which I hadn’t read in over twenty years. When I reread the texts, they had a different impact on me. Everything became more experiential as if they were speaking to my heart.

“Abhidharma offers us the tools for exploring the nature of reality. There are step-by-step guidelines, whose purpose is to free us from suffering, alleviate suffering, and unroot our suffering, which is based on aversion, craving, and ignorance.”

Traditionally, these skills have been embedded in monastic colleges and within the Tibetan community. There are not many teachings that can reach outside of that. I wanted to benefit more people, so I composed Stainless Prajna.

This text contains so many secrets related to our mind — how to be free of suffering and its causes and develop wisdom, compassion, and awareness. It is almost like learning new skills.

The Laboratory of the Mind

What is Abhidharma? “Abhi” means “higher,” and “dharma” means “phenomena.” So, the main meaning of Abhidarma is to understand the nature of reality through wisdom. In Abhidharma, we explore the nature of mind and body through the lens of sensations and feelings on an experiential level. Doing so helps eliminate the causes of suffering –ignorance and the fixation or grasping mind. When they are freed, then our mind becomes free.

Abhidharma practice is similar to doing a scientific experiment in a laboratory. But in this case, the laboratory is our own body. Buddha said, “Take my words not because I say so. You need to take my words and then see for yourself through practice. Just like with gold—after cutting, rubbing, and burning it, gold becomes genuine.” In this way, we put the Buddha’s teachings into practice.

Abhidharma offers us the tools for exploring the nature of reality. There are step-by-step guidelines, whose purpose is to free us from suffering, alleviate suffering, and unroot our suffering, which is based on aversion, craving, and ignorance.

The First Steps to Freedom

The first step to freedom from suffering is to recognize it and to recognize how aversion and craving are the root of suffering in our lives. For example, if we are told, “Do not think about pizza,” what happens? We think of pizza even more. As soon as you try to push something away, it tends to come back even stronger. We can have aversion toward friends, family, work, the environment, trees, rocks, your smartphone, society, country, the world—it could be anything. Aversion will take anything as its object, whether pleasant or unpleasant.

It is also possible to dislike something that many others enjoy — rather than bringing you happiness, it can cause you suffering. By engaging with that particular thing, that phenomenon, you develop an unpleasant sensation. As soon as you develop aversion, you engage with it by either pushing it away or manipulating your experience, which then leads to more suffering — unpleasant sensations, pain, dislike, uneasiness, and agitation. But, actually, there is no such thing as an ultimately good or bad phenomenon. It depends on who is relating to it. For somebody who really loves that thing, when they look at that phenomenon, it can be the cause of happiness and bring feelings of pleasure. For you, it is unpleasant. That is the job of aversion.

And then there is craving. If you really want to sleep at night and are in bed telling yourself, “I need sleep . . .” what happens? You can’t fall asleep. You become more alert! The more you want something, the more that craving can push that thing away. As another example, you may be preparing for an exam, studying, and looking for all the answers while trying to keep everything in your mind. But then, as soon as you enter the exam hall, your mind goes blank! You see the question and think, “I know the answer. Okay, one, two, three!” but you cannot remember the answer — it escapes you. Then, when the time is up, you remember as soon as you come out of the exam hall, but it is too late. That is the result of craving.

For example, in the West, there is a saying that “the neighbor’s grass is always greener,” right? Looking, you think, “Oh, their grass is greener. My grass is no good.” Craving is like that. We constantly yearn for what we don’t have, believing it to be better, while overlooking the beauty and potential right in front of us. This relentless pursuit of something just out of reach only fuels our dissatisfaction.

Suffering and Its Causes

What is the basis of these two causes of suffering – craving and aversion? It is ignorance or not recognizing the true nature of reality. Normally, we exaggerate, we deny, or we have completely wrong ideas. Exaggeration is how we make mountains out of molehills. If we have ten qualities within us, one negative and nine positive, what do we focus on? The negative quality. We exaggerate it and ignore and deny the nine good qualities within us.

I often give this example: If we do not have a big problem in our lives, the distracted “monkey mind” becomes a little bit relaxed and then begins looking for a problem. So one day, you go to the bathroom, look at the mirror, and see something slightly wrong with your face — “My right cheekbone is bigger than my left cheekbone.” And then you think, “Oh, this is not good.” Now, aversion and craving are involved, too, and then slowly, they become bigger and bigger. And while you are having breakfast, you are thinking about your crooked cheekbone. Then you go to your busy office or workplace and forget about it. At 5 p.m., you finish working, leave the office, return home, and relax. “Oh yeah! Crooked cheekbone!” And you go to the bathroom to look at the cheekbone. “Yeah, it is really ugly, not nice.” You think about that, and then it looks like it becomes uglier, and in the end, even when you are busy at the office, you think about your cheekbone. Then, you begin thinking everyone is looking at your cheekbone. So, you create this cycle of suffering fueled by craving and aversion.

Why does this happen? Ignorance. There are three aspects of ignorance: permanence, independence, and singularity. We do not like unexpected surprises; we like consistency — that is the grasping of permanence. We want to control things, which is the grasping of independence. We like to have singularity, meaning, “My way is better. My idea is better. I have to be number one. I have to win.” Self-centeredness. The three aspects of permanence, independence, and singularity come together to become ignorance. Then, our mind becomes very touchy and sensitive. This craving and aversion leads to suffering.

These are the causes of suffering, and the result of this suffering is pain, unpleasantness, and suffering itself. Sometimes, in the beginning, we experience the “suffering of change.” What we initially feel as pleasure, due to our relating to it with a fixed mind, becomes suffering. It is like drinking tasty juice tinged with poison, we think it tastes good, but then we become sick later. When our mind is trapped in fixation, we suffer a lot when things change. Underlying these two types of suffering — the suffering of suffering (like pain) and the suffering of change (in temporary pleasures) — is pervasive suffering. This is the hollowness, dissatisfaction, incompleteness, and longing I mentioned earlier. That is the base of all of the suffering — that pervasive suffering.

All these Abhidharma techniques are based on exploring the nature of yourself, the nature of reality, and the nature of your mind and body. Doing that will help free you from suffering.

Short Breathing Practice

Sit up straight, close your eyes, relax, and count your breath. You’ll be counting up to ten, following the natural flow of your breath.

While doing this, whatever thoughts might arise about your family, work, or anything that comes up, just observe them and let them go.

After some time counting your breath, you can let go of the counting. Just follow the breath.

Start at the tip of your nose, breathing in and then out. Be aware of your breath coming in; be aware of your breath coming out. Feel the tactile sensations of your breath. Become aware of the feelings associated with breath: When we breathe, we feel pleasant; if we stop breathing, that is unpleasant. Normally, we are not aware of these feelings.

Open your awareness to include your conceptual mind, labeling the breath “breathing in” or “breathing out.” Now you are aware of your breathing. When thoughts start to arise, label your conceptual mind thoughts arising, “I’m not doing this right, I’m not good at meditation” So many thoughts can arise, and all of this is fine. In Abhidaharma practice, whatever we notice, whether positive or negative, does not matter; it is all practice. Through Abhidharma practice we can become aware of feelings, thoughts, emotions, and more, all through the breath.

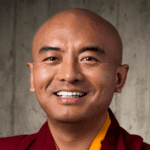

The Tergar Meditation Community happily invites everyone to join Mingyur Rinpoche in exploring the transformative Abhidharma teachings and practices in their annual transmission through upcoming Vajrayana Online courses and retreats.

See the previous pieces from this series on the Abhidharma:

Understanding Abhidharma, a.k.a. Buddhist Psychology — a Q&A with Edwin Kelley

Watch: Mingyur Rinpoche teaches on Mindfulness of the Body