The Origins of the System: A Historical Overview

I first learned about the Tibetan system of recognizing reincarnated lamas, often referred to as the “tulku system,” through the film Little Buddha, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, and Kundun, directed by Martin Scorsese. I was especially drawn to the tulku system, not only because of its magical or mysterious quality, but because of the deeply moving idea behind it: that someone would intentionally choose to return again and again, life after life, to help others.

The tulku system, which identifies reincarnated teachers, dates back to the early centuries of Buddhism in Tibet. The word tulku refers to what is called a “Nirmanakaya” or “emanation body,” a term from Buddhist teachings that describes how a deeply realized being, such as a Buddha or great master, can appear in the world in physical form to help others. Instead of being born through ordinary causes and conditions (karma) like most beings, these masters choose to be reborn out of compassion, with the specific intention to guide and benefit sentient beings. In this way, the tulku is seen not just as a regular child, but as a continuation of a being’s enlightened activity, taking a new form. Several examples of the concept of recognizing and remembering one’s past lives can be found in the four Agamas of the Vinaya Pitaka, the Jataka tales, and other sources. Similarly, the biographies of Indian masters who lived after the Buddha often include accounts of their earlier births.

“The tulku system is grounded in the deeper principle of benefiting beings. At its core, it reflects the bodhisattva’s vow of continual return, remaining in the cycle of rebirth to help others achieve liberation and enlightenment.”

While such stories are plentiful, the formal system of identifying and numbering successive reincarnations did not develop in India, but in Tibet, where it was later developed and standardized. Historically, the earliest widely recognized tulku was the reincarnation of the first Karmapa Dusum Khyenpa, a devoted practitioner of the Buddha’s teachings and the founder of the Karma Kamtsang School of Tibetan Buddhism, also known as the Karma Kagyu lineage. His recognition marked the beginning of the formal institutionalization of the system across various Tibetan Buddhist traditions, which later gave rise to major lineages and institutions, including the Dalai Lamas; the Panchen Lamas; the Chetsang and Chungtsang tulkus, the two heads of the Drikung Kagyu lineage; the Khyentse tulkus; and many other Tibetan tulku lineages, including Jonang and the Bön tradition.

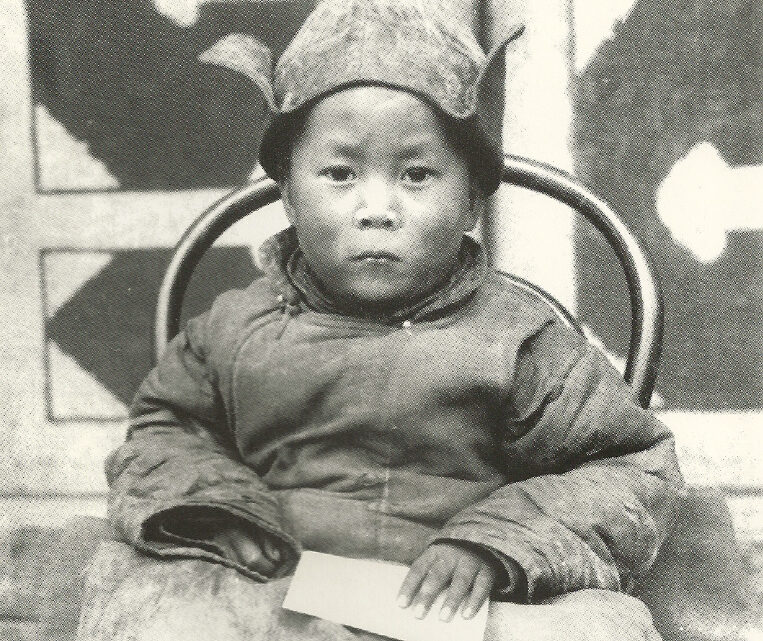

Over time, the system evolved into a deeply rooted custom within Tibetan Buddhism, shaping the transmission of teachings and leadership within monastic institutions. Tulkus are often identified when children subsequently undergo rigorous training to carry on the responsibilities of their previous incarnations. While the system has been admired for preserving wisdom across generations, it has also faced critique and adaptation, especially in the modern era.

From an outside perspective, especially among modern influencers or those unfamiliar with Buddhism, it is understandable that the tulku system can seem strange or even controversial. Often, it is compared to historical concepts like the divine right of kings or hereditary succession. For instance, in the Catholic Church, a highly educated cardinal bishop, typically around 70 years old and having served for decades and studied extensively, is elected as Pope. In contrast, seeing a young child recognized as a reincarnated master can feel surprising or confusing to those accustomed to different models of leadership. These comparisons and questions are completely natural. However, while the tulku system may seem unusual from a Western or modern perspective, it is based on a clear inner logic and serves a meaningful and practical role within the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, aimed at preserving authentic teachings and ensuring their continuity.

The Purpose and Role of the Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism

On a practical level, the tulku system helps ensure the continuity of lineages, as tulkus uphold the teachings, material possessions, practices, and unique characteristics of particular traditions, ensuring their particular lineage continues with integrity across generations. As Do Tulku Rinpoche, from the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism, explains:

There is great value in the continuity seen with teachers like Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche or Jigme Khyentse Rinpoche, where the practices and teachings of their previous incarnations, such as Khyentse Wangpo and Chokyi Lodro, are preserved and carried forward by the present tulkus.

On a more transcendent level, the tulku system offers the opportunity, although for some it may feel like a burden, to take on the role of spiritual guides, providing teachings, empowerments, and personal guidance, as well as serving as a source of inspiration, stability, and wisdom to their community. Through their lives and actions, tulkus demonstrate the possibility of realization and inspire others to develop those same qualities. While some tulkus are well-known figures, such as the Dalai Lama or the Karmapa, others lead quiet lives of service and devotion. Some even choose to live outside of the traditional system altogether.

The recognition of a tulku involves a careful examination by renowned masters, which may include tests, signs, and visions. Signs may include unusual events surrounding the child’s birth, extraordinary behaviors at a young age, or special qualities that seem to indicate a realization of their previous life. Visions can occur to realized masters or close disciples, offering direct insights into the identity of the tulku.

The tulku system is grounded in the deeper principle of benefiting beings. At its core, it reflects the bodhisattva‘s vow of continual return, remaining in the cycle of rebirth to help others achieve liberation and enlightenment. This selfless dedication to others’ well-being is central to the system and illustrates the profound Buddhist perspective that enlightened actions extend beyond one lifetime, and compassion can arise in many forms, meeting individuals where they are and aiding beings in ceasing the causes of suffering.

Training, Lineage, and Modern-Day Relevance

Although I have not personally experienced the life of a tulku, I imagine that one of the most significant challenges they face is managing the immense expectations placed upon them. These expectations may be imposed by the community or self-imposed by the tulkus themselves. It must be challenging to navigate such high levels of attention, especially at a young age, while also being tasked with upholding the teachings of one’s lineage and lineage holders.

We can see the immense importance of study and deep understanding in this process. To be entrusted with the teachings and practices of the lineage, it’s crucial for a tulku to engage in extensive study, reflection, and practice. Without a genuine understanding of the teachings, how can they effectively transmit them to others? The rigorous training and study that tulkus undergo ensures that they do not merely repeat words, but are able to communicate the meaning of the teachings with clarity and authenticity. As Wyatt Arnold, a tulku from the U.S., explains:

Many of the tulkus who have done the most for Buddhist preservation and transmission have gone through many years of philosophical study, received many teachings and empowerments from their teachers, and have dedicated their time to practice. So, without those blessings, the tulku “system” would have probably gone extinct or completely lost its credibility by now.

However, there are instances where some believe that, having received these teachings in past lives, they do not need to study or learn them again in this lifetime. However, I have often heard my teacher, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, say that such an attitude is completely mistaken and even potentially harmful to the teachings of the Buddha. The teachings are not simply passed down from one life to the next as if they were a passive inheritance. In every lifetime, there is a need for study, personal reflection, and experiential realization. Without this, the teachings can be misinterpreted, and the responsibility of passing on the Buddha’s wisdom can be compromised.

Raising a Tulku

Wherever power, fame, and money are involved, human delusion is never far behind. And so naturally, those surrounding tulkus may sometimes make unwise decisions or behave in ways that contradict basic Buddhist principles. This creates a challenge, especially for Tibetan monks or nuns who, as celibate practitioners, are often not familiar with the emotional needs and upbringing of young children. While the young tulkus receive strong spiritual training, their emotional development can sometimes be neglected, simply because their caregivers may lack the experience or resources to raise a child. In contemporary times, when tulkus have gained recognition in the West and are born to Western parents, their families often leave it to the child to decide whether to follow the path of a tulku. This perspective, however, overlooks the appropriate training they may need if they choose to embrace the role of tulku later in life.

Tulku Ngawang Tenzin Rinpoche says that personally, he thinks it is very important for those raising a tulku to understand pedagogy, child psychology, and how various influences and surroundings shape a young mind. In traditional Tibetan Buddhism, there are often fixed ideas about how to raise, teach, and control a tulku. This needs to change. We should raise and educate tulkus with skill and care, paying attention to how they feel and experience things physically, emotionally, and mentally.

The Future of the Tulku System

Today, the tulku system faces different challenges. The tulkus themselves must decide whether to continue with the role assigned to them, and if they do, must accept the responsibilities that come with it. This is especially true in the modern world, where some tulkus are raised or trained in the West. In such contexts, balancing the community’s expectations with the demands of study and genuine practice becomes even more complex. Tulkus today must not only engage deeply with the religious and cultural traditions of their lineage, but also navigate a globalized world that often values very different things, like individualism, material success, skepticism of traditional teachings, and especially a culture that worships youth and physical beauty. So the teachings, advice, and wisdom from their teachers and mentors become key for them, as well as their decision to live as monastics or as lay followers of the Buddha.

The Buddhist community itself, the sangha, also has a role to play here. Some people tend to go to extremes when relating to tulkus: either showing complete devotion, which can resemble blind faith, or entirely rejecting the system due to disappointment in tulkus who have not met expectations. Both are best avoided. Disappointment often arises from unrealistic expectations, and Buddhism emphasizes the importance of developing discernment. It also explains that devotion develops in stages: it begins with admiration, then progresses to aspiration, and ultimately becomes confidence or conviction. As Trulshik Rinpoche once said, “In the beginning, don’t praise tulkus too much, go step by step. If a tulku puts in the effort to follow the actions and way of life of their predecessor, then we can say that this is truly the incarnation of such a master.” In other words, give them the proper training, but wait to see how they manifest in the future. I’ve also heard the fourteenth Dalai Lama and Chetsang Rinpoche, the head of the Drikung Kagyu tradition, give similar advice on the subject.

Raktrul Rinpoche notes that it is thanks to the tulku system that the tradition has endured for so long. Broadly speaking, when it comes to the heads of the different schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the Nyingma school, historically known for its decentralized structure, and the Kagyu school, both tend to rely more on tulkus to appoint their leaders and preserve their lineages and teachings. However, their leaders are traditionally respected for being accomplished practitioners and scholars in their own right. The Sakya tradition, by contrast, follows a lineage-based model in which leadership is passed down within the noble Khon family. These successors are also required to undergo rigorous education and study and must receive proper training to assume such a position. The Gelug school appoints the Ganden Tripa, the successor to Je Tsongkhapa, based on scholarship, effort, and commitment to practice, regardless of family background or tulku status. Rinpoche notes that each approach has its own strengths and challenges.

According to Simon Bianco, a clinical psychologist and longtime student of Tibetan Buddhism, “The two main challenges facing the Tibetan tulku system today are, first, the need to adapt the education of tulkus to the modern world while keeping their own lineage training, and second, the way reincarnated lamas are recognized. Instead of granting the status of tulku at an early age, recognition should come only once genuine interest and qualities are demonstrated, placing importance on present-life merit and training rather than hereditary recognition. This approach could preserve the strengths of the system.”

In any case, the relevance of the tulku system today lies in its ability to connect the deep wisdom of the past with the needs of the present. While the form of the system and people’s expectations may continue to evolve, the essential role of tulkus — offering guidance, embodying compassion and wisdom, and preserving the dharma — remains vital to the continued flourishing of the Buddha’s teachings in the world.