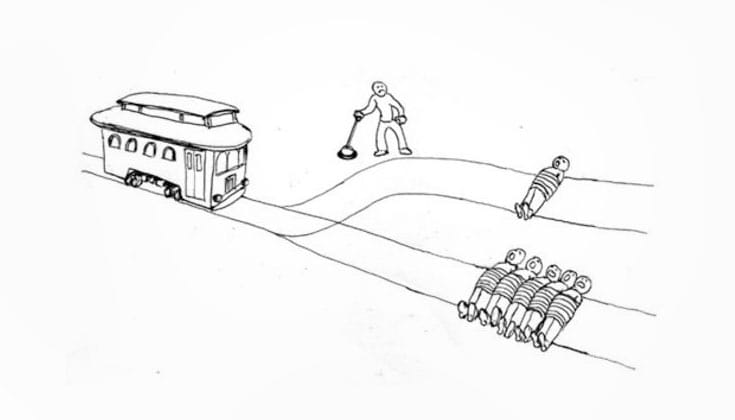

A trolley is coming down the tracks, and it’s going to hit five people. You have the option to flip a switch to divert the trolley to a different set of tracks, where it will hit one person. Do you hit the switch, dooming one person while saving five?

Let’s try a different scenario.

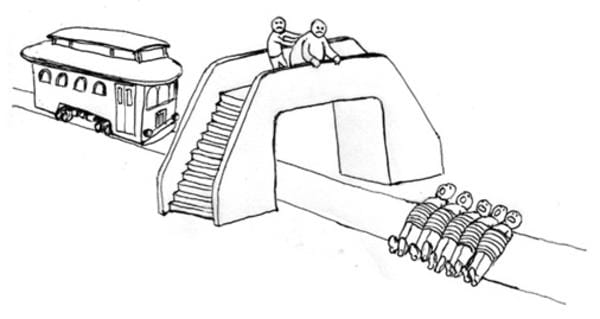

A trolley is coming down the tracks. It’s going to hit five people. You’re standing on a bridge over the tracks next to a large person, whose heft could stop the trolley. Do you push the large person off the bridge to save the five people on the tracks?

Those questions are versions of a classic and infamous moral dilemma called the “trolley problem,” which is the center of Harvard professor Joshua Greene’s research. In a presentation at the Aspen Ideas Festival last week, Greene reported on his research findings, as reported by The Atlantic‘s Alexis Madrigal.

Greene has found that a large proportion of people would flip the switch in the first scenario, while most people would not push a person off the bridge in the second scenario — even though the outcomes are the same. The implications of having to push someone are just too sticky. Two groups, however, are perfectly comfortable pushing the bystander in front of the trolley: those are economists and psychopaths. For them, the trolley problem is purely a question of numbers: logically, it makes sense to sacrifice one life and save five.

Greene had a thesis student, Xin Xiang, who posed the question to Buddhist monks in Northern India. How did they respond? The majority of monks said they would push the person off the bridge.

“Their results were similar to psychopaths—clinically defined— and people with damage to a specific part of the brain called the ventral medial prefrontal cortex,” wrote Madrigal in his report.

That conclusion might seem shocking if you have an image of Buddhism as a spirituality of pacifism. In fact, in the Anguttara Nikaya, the Buddha reportedly said that it is impossible for an enlightened being to take a life.

However, Greene notes an interesting difference between the logic of the monks and the economist-psychopaths. In contrast to the latter’s purely utilitarian view, the monks saw the trolley problem as a matter of compassion:

“I think the Buddhist monks were doing something very different,” Greene said, as reported in The Atlantic. “When they gave that response, they said, ‘Of course, killing somebody is a terrible thing to do, but if your intention is pure and you are really doing it for the greater good, and you’re not doing it for yourself or your family, then that could be justified.’”

In Buddhism, “ethics” or “morals” generally refer to three components of the Buddha’s eightfold path: “right speech,” “right action” (in which taking life is discouraged), and “right livelihood.”

In the Spring 2017 issue of Buddhadharma, four Buddhist teachers discussed the topic of ethics and morality. In that conversation, Pema Khandro Rinpoche spoke to the issue of action versus inaction:

“Traditionally, karma would be at the center of a conversation about ethics. We should consider this idea of karma in terms of a sense of vigilance about our actions. Our actions have consequences; so too does our nonaction. Our nonaction is also difficult to undo.

“Compassion is actually a profound responsiveness rather than passive empathy, as we see embodied in the image of Green Tara, with her foot extended forward to step into action. This is an important conversation for us to have. What is compassion, really?”

Of course, Pema Khandro Rinpoche wasn’t talking specifically about pushing someone off of a bridge into the path of an oncoming train; but her words seem applicable nonetheless.

The implications of this question are vast. We can think of lots of examples where, as Buddhists, we might face a challenging dilemma. And, from a Buddhist perspective, there really is no absolute right or wrong. Reading the teachings, it would seem that that is the point.

As Zen priest and Buddhadharma deputy editor Koun Franz writes, “When it comes to ethics, Buddhism doesn’t offer a lot of absolutes; if anything, it raises questions… as in all aspects of the path, in the practice of ethics we are called upon to see through the ambiguities and the what-ifs, to find some clarity, and from there to act, to take some actual step forward.”

It seems that a Buddha is the perfect embodiment of ethical living — effortlessly helping others without doing any harm. But, on the path to buddhahood, it is all we can do to grapple with our ethical questions.

So, what do you think? Would you flip the switch? Would you push a person off of a bridge? Let us know your thoughts on Facebook and Twitter.