As Buddhists, we spend so much of our time talking about awakening, about developing a compassionate heart and an enlightened mind, about freedom and liberation. While the centrality of those experiences can’t be disputed, neither should they become an excuse for denying the reality of our situation right now. We give short shrift to the places where we get caught, where we are not inspired or really not living up to our vision of who we aspire to be. From my perspective, spending our time longing for some idealized state of mind is not genuine Buddhist practice but merely spiritual bypassing. If we focus only on awakening, we miss most of the spiritual practice. I’m much more interested in how we practice with not awakening, with not being enlightened, because, frankly, those states of being are more present in my life than not.

Lately, as I strive to promote diversity and anti-racism both inside and outside of dharma communities, I’m finding new depths of disappointment and disillusionment at the limitations of my own capacities, at the imperfections of our communities, and at the harm occurring in our larger culture. We don’t live in an enlightened world—have you noticed? As a dharma teacher, I was trained to teach the insights and kindnesses that I have felt. However, these days I feel propelled to teach from where I am—to be real and authentic in the moment, in the midst of places where I do not have answers, and from the limitations of my own flaws.

Beyond an occasional mention of the five hindrances, which are numerically contained and therefore perhaps conceptually manageable, acknowledgement of the opposite of freedom and awakening is largely absent in many dharma teachings. In more than thirty years of Buddhist practice, I have rarely encountered any discussion about what happens when enlightenment doesn’t happen—really doesn’t happen. Or about what occurs in that potential crisis of faith, that edge of practice, when awakening is no longer a sufficient motivation for practice.

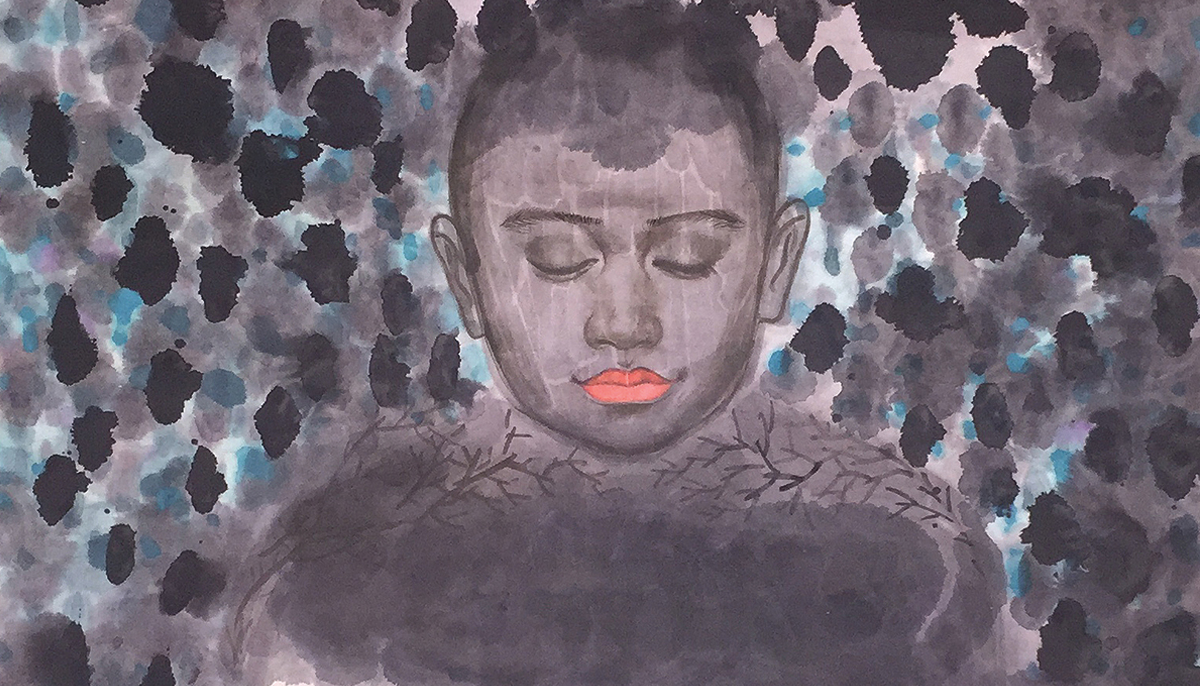

We do not like to turn to the unpleasant reality of not awakening, so we often push it away and hide our imperfections behind a facade of serenity.

Vedana practice (the second foundation of mindfulness) teaches that each moment of our lives is experienced as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral; the unconscious mind tends to lean toward pleasant experiences and push away the unpleasant ones. And this happens even in our practice of awakening. We do not like to turn to the unpleasant reality of not awakening, so we often push it away and hide our imperfections behind a facade of serenity.

Dharma teachers aren’t immune to this. A close friend was the primary caregiver for a family member who was struggling with a debilitating illness. They were as close as two human beings could be, and when that family member finally died, my friend’s grief felt inconsolable and interminable. In response to the depth of that grief, a well-meaning dharma teacher told my friend, “Arhants do not need to grieve.” My friend was shocked at this remark, as was I. How can we ignore, deny, or repress the reality of our lives and still say we are living mindfully?

Is the point of practice to negate and deny our very tender, human experiences? Even if we are encouraged to “go through” them rather than go around them, the value is placed on the getting through, rather than on being in and with. What happens when we’re stuck in the quicksand of life’s circumstances with no foreseeable resolution? What if the limitations in our lives prevent us from seeing a path out of despair—whether existential (in the form of disillusionment), psychological (in the form of loss or depression), or sociocultural (in the form of racism, misogyny, heterosexism, transphobia, ableism, and other outgrowths of oppressive cultural unconsciousness that are certain to last well beyond any single human lifetime)?

When we become aware of our disillusionment or disappointment, our next impulse is often to try and fix whatever it is we think is broken so we don’t have to deal with our feelings of despair. But what if nothing is actually broken and yet the disappointment and hopelessness remain? The world is imperfect and flawed with the reality of the first noble truth. It is what it is, and often there is nothing we can do. No wonder we feel despair.

If we don’t look deeply into these states of non-enlightenment, we deny the authentic reality arising in the moment. That contradiction can create a crisis of faith in the dharma itself. So how do we turn toward that despair, even immerse ourselves in it, as part of our spiritual practice?

We can’t experience awakening without experiencing not awakening.

We must dig deep into our practice in order to navigate the extremes of despair and disillusionment. We must listen to what is underneath it all, to where freedom is calling from, by asking: Can I open to this? Can I turn toward this? Or in the inadequate language with which we must communicate, can I love this too? Can we incline toward the despair and imperfections of this life with the same diligence we give other objects of mindfulness? Can we practice presence when life feels impossible?

It may seem counterintuitive, but when we practice awareness and offer kindness to the uncooked, imperfect aspects of our lives, we actually strengthen our mindfulness. We don’t need to attach to either awakening or non-awakening; neither is anything more than an experience to hold with tender awareness.

Awakening and not awakening are two sides of the same coin. They are the same experience. We can’t experience awakening without experiencing not awakening. We can’t experience insight without becoming intimately familiar with our conditioned patterns.

Thus, in exploring the full range of our life and practice, I wonder what the space between the seven factors of awakening (mindfulness, investigation, effort/energy, joy/rapture, tranquility, concentration, equanimity) and the seven factors of non-awakening (unconsciousness, boredom, lethargy, depression, agitation, distraction, reactivity) might look like. What is the range of experience between unconsciousness and mindfulness? Life is not dual. Mindfulness and unconsciousness are not light switches to be simply turned on or off. What are the subtle levels of gray in between the extremes of these factors? Where does unconsciousness bleed into consciousness? If I can feel that relationship, then I can stay connected to mindfulness even in my lapse of mindfulness. I can stay in alignment with awakening even in my failure to be awake.

Likewise, what is the incremental set of sensations, thoughts, and feelings between boredom and investigation? Where is the transition between lethargy and energy? How does despair connect to joy and rapture? What are the nuances between the extremes of agitation and tranquility? Where is the breadth of landscape bounded by distraction and concentration? And what happens between the states of reactivity and equanimity?

The nuanced spectrum of experience between despair and joy might look something like this:

Despair—Hopelessness—Depression—Grief—Pain—Sadness—Regret—Distress—Dejection—Worry—Heavyheartedness—Gloominess—Apprehension—Confusion—Irritation—Questioning—Dullness—Indifference—Neutrality—Nonchalance—Stillness—Coolness—Calm—Ease—Relaxation—Contentment—Replenishment—Comfort—Gladness—Cheer—Mirth—Wonder—Delight—Excitement—Rapture—Collective Joy

In the Western Vipassana tradition, there is a popular acronym, RAIN, which encourages us to Recognize the moment, in order to have Acceptance of the moment, so that we can Investigate the moment’s true nature, in order to realize our Non-identification with that moment arising—the last of which is a state of insight and awakening. All the factors of RAIN are actions of incremental progress toward awakening. But this acronym belies the messiness of our painful and complicated lives. In a similar parallel, Dr. Elizabeth Kübler-Ross outlined five stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—that the human psyche experiences when coming to terms with loss and trauma. That is, we must pass through denial, anger, bargaining, and depression before acceptance is possible. When these five stages are inserted into RAIN—after the factor of recognition (mindfulness) but before our acceptance of the moment arising—our practice of insight might look more like this:

Recognition—Denial—Recognition—Anger— Recognition—Bargaining — Recognition—Depression— Recognition—Acceptance (… maybe)—Investigation—Non-identification (… maybe)

This sequence feels so much more authentic and realistically human to me. It’s never either/or. Life is so much more complex than that. Our experience isn’t characterized by just the polar opposites of awakening and not awakening but rather by all of the contours lived in the range in-between. If we can monitor and be aware of the totality of the experience of awakening and not awakening, we can stay connected to both without bypassing either. Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote: “We must accept finite disappointment, but we must never lose infinite hope.” We need both—the absolute aspiration of unconditioned hope and the relative path, which is filled with constant disappointment. If we have only the aspiration of the enlightened ideal, how do we ever get there? If we only have the path with no guiding North Star, where are we going and what is the point of it all?

The inspiration for our practice often rests on one single moment: the Buddha’s awakening beneath the bodhi tree. But that is not the totality of his biography. Tradition tells us it took him thousands of lifetimes to awaken. We have stories about the Buddha’s previous lives in the Jataka tales, and in them he was not perfect, not fully awake, even though each illustrates how the perfections (paramis) of dharma practice ripened in those lifetimes of the bodhisattva. They show the paramis ripening, but not yet ripe. All those moments of non-awakening serve an indispensable purpose in the path to awakening. We must fully live the moments of non-awakening in order for freedom to arise. We can’t simply aspire to enlightened states of mind and heart without a realistic, flawed human path.

In the Saccamkira Jataka, a prince in danger of drowning is pulled from the water by a beggar ascetic (the future Buddha). Being an untruthful and ungrateful person, the prince disingenuously tells the future Buddha that he can come anytime to his kingdom for support. When the prince becomes king, the ascetic visits his kingdom. Instead of supporting the ascetic, the king has him beaten in the streets and orders his execution. When the ascetic is asked in the streets what the trouble is between him and the king, he tells the story. The populace and guards become so enraged that they kill the king and drag his body through the streets, dumping it in the moat. The ascetic is then anointed the new ruler.

While perhaps indicating a kind of justice, the outcome of the Jataka is not exactly a restorative, compassionate one. As with many of the parables, the Saccamkira concludes with a version of this phrase: When his (the future Buddha’s) days were come to an end, he passed away according to his deeds. And according to the imperfect deeds of most of his lives, the Buddha did not awaken.

We have all been there, when we have done our best and yet, we may be far from perfect.

That means, at least metaphorically speaking, before the precious moment of awakening, there were thousands of other times the Buddha-to-be did not awaken. If he was practicing mindfulness (and it is said one cannot become a buddha unless there is an initial intention to consciously do so), at some point in each of his unenlightened lives he must have become mindful of the fact that he was not awake. He became aware of his own limitations, his own failures, and his own shortcomings, which, despite his very best efforts, cumulatively were not going to lead to enlightenment in that lifetime. How disillusioning after doing the best he could in service of such goodness.

Did the Buddha experience despair? Did he have self-pity or grief over enlightenment in that particular lifetime? Did the Buddha go through Dr. Kübler-Ross’ five stages of grief? Because he was human, I would guess the answer to these questions would be “yes.” He went through what humans go through when there is significant loss and despair. The future Buddha, in his humanity, would have needed to experience denial, anger, bargaining, and depression before acceptance was possible.

Yet the Buddha returned to practice—whether he was enlightened or not, despairing or not. That, to me, is significant. What would you do? What do you do? We have all been there, when we have done our best and yet, we may be far from perfect. We try for the best solution we can, and there might be some collateral injury, even serious harm, incurred along the way. We are not enlightened. How do we reconcile the aspiration to be of benefit with the inevitable harm we cause? How do we make all of it our spiritual practice?

When I do metta practice, cultivating love and compassion toward all beings in all worlds and in all directions, there is an ancillary blessing that I hold in my mind:

May I be loving, open, and aware in this moment;

If I cannot be loving, open, and aware in this moment, may I be kind;

If I cannot be kind, may I be nonjudgmental;

If I cannot be nonjudgmental, may I not cause harm;

If I cannot not cause harm, may I cause the least harm possible.

Thus, even in my imperfections, even in my failures, I can still incline my heart toward freedom. This is how I see the paths of awakening and non-awakening interweaving. This is freedom in the midst of suffering. This is resilience despite the forces of violence and oppression. We can create beautiful lives right where the world is not yet awake.

Each time we practice awareness and kindness, we transform not only our personal world but the world itself. We begin to be able to hold the unholdable, to connect the broken heart and the raging mind. We look for the precious wisdom embedded within that bitter rage, and as soon as we begin to look, we are no longer consumed by the rage itself. We turn toward the direct experience of despair and weave it into care, love, and, dare we say, freedom. This is the magnitude of our spiritual practice. It asks us to include all the contradictions and paradoxes of awakening and not awakening and everything in between. It is the in-between—the range from extreme to subtle, the spectrum connecting opposing forces—that constitutes the totality of our lives, our practice, and our freedom.