Q: I have zero interest in enlightenment. To me, Buddhism is about ethics—it’s a path to reduce harm and hopefully provide benefit to others. Is that enough, or am I missing the point?

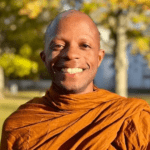

Bhante Sumano: For you at this moment, Buddhism as ethics will have to be enough. Practicing morality, virtue, ethics—being of benefit to oneself and others—these are activities the Buddha always applauded. It just so happens he also said there was something greater: the possibility of enlightenment.

Buddhist traditions offer various perspectives on bodhi—enlightenment or awakening. Here, I offer one of the simplest descriptions from the Pali texts: enlightenment is the end of greed, hatred, and delusion. No more grasping, no more hating, no more ignorance. Freedom.

You can’t fake interest, nor should you. No need to feel guilty, either.

You’ll find a litany of synonyms and metaphors for enlightenment. Some call it a refuge, a sanctuary, the far shore, or the sublime. Essentially, enlightenment is the attainment of true peace, one born of seeing reality clearly.

Enlightenment, then, doesn’t preclude ethics, or sila. It couldn’t. True peace can never be based on harming oneself or others. Awakening must involve ethics. In fact, if you’re practicing ethics, you’re practicing for enlightenment. What is enlightenment if not the pinnacle of ethical conduct?

But this pinnacle can only be reached by developing the mind. After all, it is the mind from which all action—virtuous or not—springs, and its workings are profoundly subtle.

Transforming such a mind requires more than ethical conduct. It requires concentration and wisdom, completing the trifecta of sila, samadhi, and pañña, wisdom. All these qualities build on and support each other. So when you’re practicing ethics, you’re also developing your powers of awareness and insight—qualities that lead to awakening.

The Buddha was not interested in coercing anyone to practice in a particular way, though. Instead, he invited people to see the benefits of whatever path of action they chose. Of course, as a teacher he gave guidance based on his deep wisdom and experience, but it was up to the individual to do as they saw fit.

You can’t fake interest, nor should you. No need to feel guilty, either. You don’t need to “believe in” or care about enlightenment to develop the heart. Besides, if you change your mind, the potential for awakening will still be there.

So yes, Buddhism is about ethics and reducing harm. But it’s also about so much more: it is about the vast potential of the mind to be released from distress, about unlocking immense generosity, kindness, and understanding. Such a mind would surely benefit the world.

Still, don’t take my word for it. Practice deeply and sincerely, and see for yourself how shedding greed, hatred, and delusion feels. The relief of a joyful, mindful walk or a serene sitting session is but a taste of the peace of a mind released. And when we have even a little bit of peace, it can only spread to others as well.

Jisho Sara Siebert: Your question is wonderful, because many of us practice Buddhism out of a wish to relieve our own suffering, and you have already expanded your viewpoint beyond your small self. True expansion or dissolution of view is what we mean by enlightenment––it is not some altered state. From the viewpoint of enlightenment, unethical action doesn’t make any sense; there is a natural flow of ethical action from an awakened viewpoint. But can ethical action exist without awakening?

I was born to an atheist mother, who is one of the most ethical and caring people I know. I have seen her up close, as she watched her mother die slowly and now, as she watches my father’s struggles with Alzheimer’s. Ethics without any cultivation of, or desire for, a spiritual path seems to be working for her.

For me, ethics without the mind of enlightenment did not work. All around, I see the pitfalls of seeking to do compassionate things without grounding in awakened mind. I have spent about twenty-five years as a bit of a reluctant nomad, seeking to prevent and respond to sexual and domestic violence in such places as Liberia, Uganda, Haiti, Papua New Guinea, and Iowa, and at times, the suffering has been intense and all-consuming. In each community, there have been many compassionate beings, listening and acting out of a beautiful and awakened mind. But there have also been peacekeepers who sexually abuse little girls, decadent parties by expats working in refugee camps, and racism, egotism, and callousness in the face of need. In these cases, people were led to their positions by a sense of ethics, yet their work brought suffering.

How can we best live in a way that benefits others? The koan is yours.

One day in Haiti, I walked along a dusty street lined with little turquoise, pink, and grey houses, feeling weak and off-center and on the way to a day of “ethical” service. It smelled like a mix of flowers, the sewer, and burning trash. People along the path, drawing on centuries of legitimate grievances, shouted slurs at me as I passed while others stared, stone-faced. This was not so different from most mornings in that particular community, but that day I felt unable to continue.

I stopped and closed my eyes for a moment, wishing for a patch of sun in which to lie down. I thought only briefly of Buddha. Suddenly, I sensed an energy in the top of my head open; I felt light flow in through the top of my head and out my feet. I looked around again at the same scene, smiled widely at those shouting at me, said hello, and kept walking. Stone faces cracked open, radiating warm smiles.

How can we best live in a way that benefits others? The koan is yours, so I bow and hand it back to you. Please sit with it with your whole heart.

Gaylon Ferguson: This is one of those questions that has several important insights built right into it. Yes, the path of buddhadharma is about ethics or right conduct (sila)—and it’s also about right mindfulness and meditative engagement (samadhi), as well as knowing the true nature of reality (prajna). These traditional “three wheels of training” are elaborated in the earliest teachings of the Buddha on the noble eightfold path, where we are encouraged to study the view, practice meditation, and manifest our understanding in right speech, right action, and right livelihood.

This question beautifully leaves open the possibility that there is more to the path of awakening than ethics, more than we have already understood about the Buddhist path altogether. This is an admirable sign of humility, an absence of the arrogance that is certain that “this is all there is to know, and that’s that.” This and many other genuine questions arise in what Suzuki Roshi praised as our “beginner’s mind.”

Enlightenment and ethics are not the same thing, nor are they different.

When we engage meditation, study, and action, we allow our experiences in practice and everyday life to change us. This path of experiential transformation may gradually shift our interest in enlightenment. This isn’t a matter of forcing ourselves to agree with previous dogma, to believe something just because it’s ancient. Instead, we find ourselves opening and letting go of fixations, feeling wider empathy and deeper compassion, connecting with others in community and solidarity amidst the turbulent changes and challenges of our world. This means that we may—nothing is certain or guaranteed here—come to a different understanding of who we are (and are not), who those around us are (and are not), and how we might move away from causing harm and toward being of greater benefit. Attaining what is called “unexcelled, complete perfect enlightenment” is said to be a wise, skillful, and powerful way of caring for all beings—the ultimate ethical realization. Enlightenment and ethics are not the same thing, nor are they different.

The path also invites us into the deeper meanings of “enlightened being.” Those who have realized their true nature are called “buddhas,” meaning “awakened, enlightened ones.” Originally, a singular historical person was “the enlightened one”; however, later practitioners came to understand “buddha” as the true nature of everything. We might call this larger dimension of wakefulness “Cosmic Buddha.” The historical person known as Shakyamuni was, of course, part of this primordial wisdom display, but so are we and everyone and everything around us. This is the vastness that is the inner meaning of the small word “buddha.” So your question about not being interested in enlightenment opens up a new question: What is enlightenment?