As a young white girl growing up in Mexico, as a single parent in a Buddhist sangha, and as a gay woman teacher of Zen, Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara has always felt like an outsider. Her spiritual journey has been a search for connection.

“In Zen, there’s this quality of the vast integration of everything. We can’t miss that just because we’re separate, or think we’re separate,” says O’Hara, who is abbot of the Village Zendo in New York City and a founding teacher of the Zen Peacemaker Family. “Our practice reminds us that we have a responsibility to the rest of the beings around us at all times.”

O’Hara grew up in the border town of Tijuana and attended Catholic school in the United States in the 1940s. “I have always felt like an outsider, since I was a child,” she says. “First, everyone at my school was Mexican but me, and while I spoke Spanish, I was still the ‘gringa.’ And because my stepfather was a dark-skinned Mexican and I saw how he was treated in certain situations, I’ve always also been very sensitive to issues of prejudice and bias and privilege.”

O’Hara discovered the Beats when she was in high school. “I read my first Gary Snyder poem and thought, ‘Oh, this is a whole different way,’” she remembers. “I’ve always been questioning and rubbed up against accepted beliefs, and I think Zen does that. It says, ‘Wait a minute, don’t just accept the accepted reality. Look deeper.’ That has always appealed to me.”

At UC Berkeley, O’Hara studied English literature and did doctoral work at New York University in media ecology. She worked as a professor in New York, traveled to many countries, and became a single mother. She read Buddhist texts throughout but couldn’t find a good situation where she could practice in earnest.

“As a single parent I found it extremely difficult to enter into any Buddhist community with a young child,” she says. “It was a difficult time because I knew that I had a passion for the dharma, but I couldn’t find a home that seemed conducive to my idea of mothering.”

Then, while in Europe in her mid-thirties, O’Hara went to register for a tai chi workshop in a Buddhist monastery and ended up studying Zen instead. “I finally really sat down and got good instruction on posture and breathing,” O’Hara recounts. “It was like coming home. It was the most amazing thing.”

It was always Zen for me. I have sat in other Buddhist communities, because I love them and I appreciate all traditions. But my heart’s always been with Zen.

O’Hara went to different Buddhist centers to try to find one that suited her, but many made her uncomfortable. They were too hierarchical, too sober, too restricted. “I think you could say I’m a little rebellious and suspicious of authority. I matured in the sixties, so I was involved in the free speech movement, the anti–Vietnam War movement, all of that. And in various Buddhist communities you had the people in power and the people not in power.”

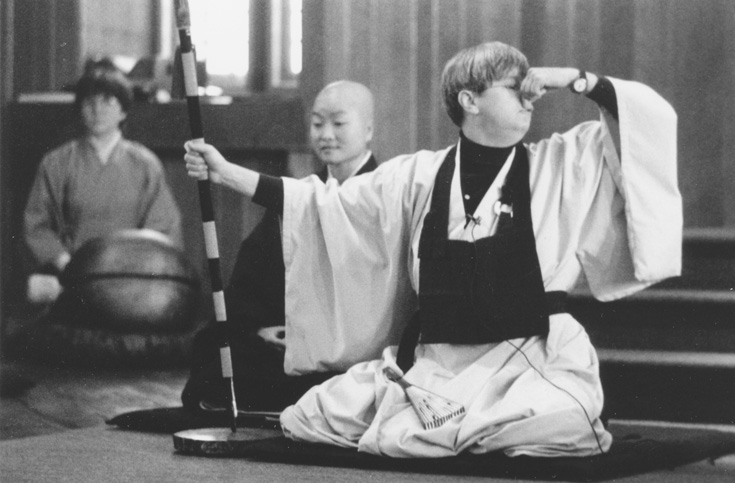

When her son was old enough in the early 1980s, O’Hara began to practice at Zen Mountain Monastery in Upstate New York with the American Zen teacher John Daido Loori, Roshi. But the challenge of heirarchy remained.

“No matter where you practice, in Zen there is a quality of authority,” she notes. “It’s not like the aesthetic in the commercial world of ‘That’s so Zen’ and you get yourself a Zen lamp and a Zen this and a Zen that. There is the capability of Zen to be really harsh, or to sound harsh. So, my struggle was always, ‘How can I allow myself to be humble and open and still honor my own feeling that that level of authoritarianism is unhealthy?’”

One factor that helped was Daido Loori’s view of women. “As an American teacher, he didn’t have any issue of men versus women, and whenever the gender was vague in a koan, he encouraged us to switch it to female.” O’Hara says that although she is sensitive to the challenges Buddhist women have faced, and continue to, she has been lucky in her own journey with Buddhism. “Right off, Loori began talking about my starting to teach. My attitude was, ‘No, I’m just here to face the wall and meditate, thank you.’ But he was very encouraging.”

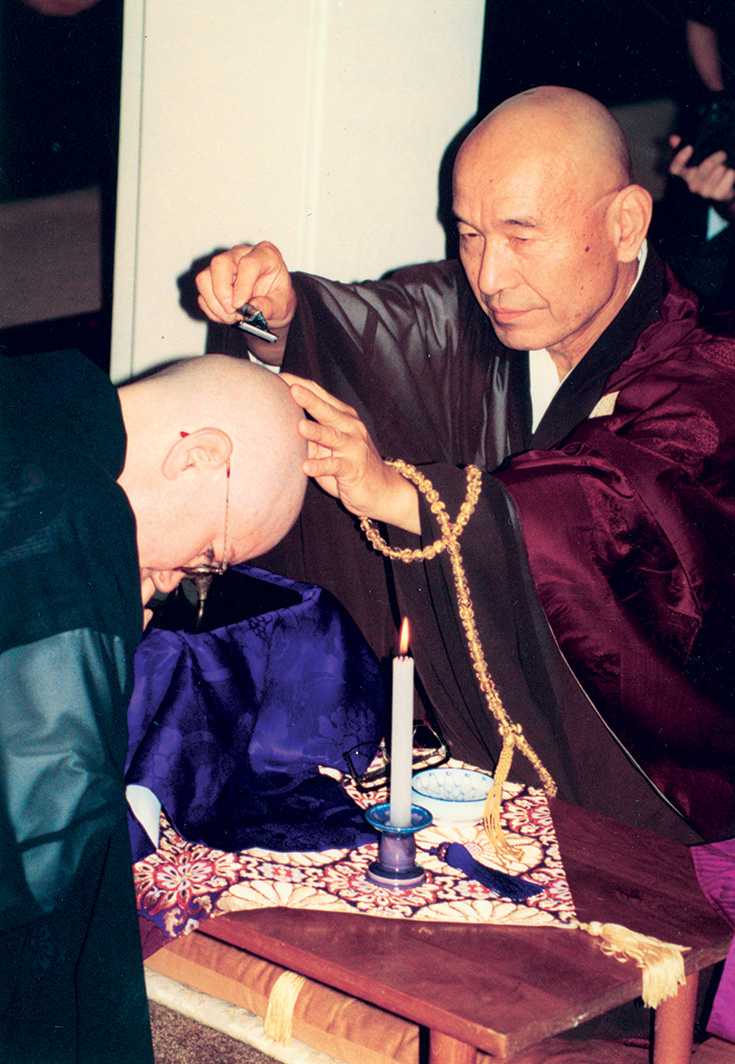

When she next began to study with Taizan Maezumi Roshi, who brought together the Soto and Rinzai traditions, O’Hara says she knew she had found her true teacher. “The whole feminist movement was going on at the same time Buddhism was coming to the West. Maezumi Roshi came to this country as a young man and fell in love with the freedom and thirst for the dharma here. He was very open to the new traditions, and he empowered a lot of women. Studying with him was like studying with a woman. It was very peculiar. He was this wonderful feminine energy and we would sit in this darkened dokusan room and cry together [laughs].”

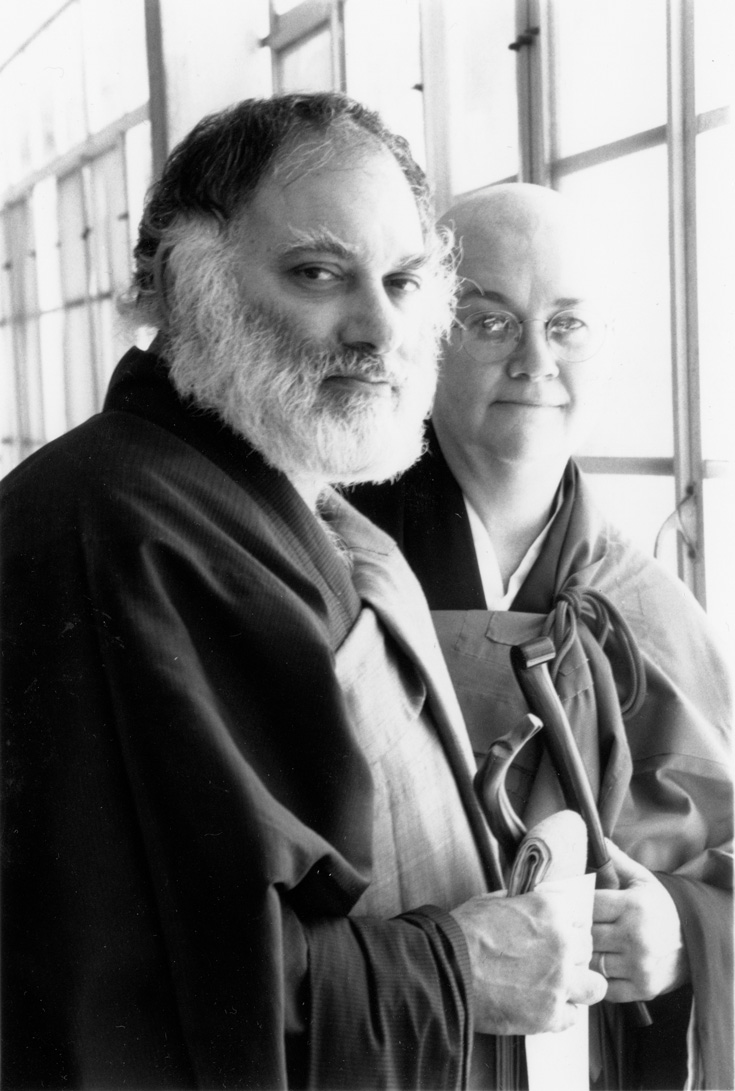

When Maezumi Roshi died, O’Hara received dharma transmission from Roshi Bernie Glassman, one of Maezumi’s leading students, who died earlier this month. Glassman’s focus on social engagement and peacemaking came to underlie much of her vision of Zen practice.

“It was always Zen for me. I have sat in other Buddhist communities, because I love them and I appreciate all traditions. But my heart’s always been with Zen.”

As O’Hara was pursuing her spiritual path, she taught media studies for twenty years at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. Her approach to information technology and the way we consume media mirrored the paradigm-shifting character of Zen.

“When we practice something like Zen, our minds change in the way we apprehend material, and the way we apprehend information changes with the forms that we use,” says O’Hara. “Someone who meditates lying down listening to music has a different experience than someone who is sitting up straight staring at the world. And so it is with media.”

In the early 1970s, O’Hara cofounded a program at NYU called “Interactive Media.” At the time, the program was revolutionary, starting with using split-screen televisions as a way for people to talk to each other. “The communication wasn’t one-way,” O’Hara says, “and that was the key to a more horizontal power structure, to elevating a population and putting it on an equal status with the people in power.”

One of the first projects O’Hara was involved in was a large National Science Foundation project to see if it was possible to deliver social services to seniors through media technology. “It was in a little town in Pennsylvania. We connected all the senior citizen centers to the mayor’s office,” she says. “Then once a week the seniors would interview the mayor and it would go out on the cable system for the whole county.”

Later, O’Hara worked with other marginalized populations, including kids in a drug treatment center to whom she taught videography. When she saw they needed ways to focus their attention, she taught them meditation. She also worked with developmentally disabled people and their parents. “As the technology grew, I became more and more interested in how media affects the culture as a whole,” she says, “the ways it connects us and the ways it separates us.”

As O’Hara worked to connect people through technology, she realized what she needed in her own life was connection through a Buddhist community.

“One day, when I had dressed and gone out the door and had not sat in meditation yet again, I realized I had never created a discipline of sitting. I needed other people to join me to sit.” O’Hara created a sitting group in her home. She had no intention of being a teacher; she was just offering a space where people could meditate. “I bought some cushions. I threw out my sofa and made it a little Zen dome in my apartment, big enough to accommodate twenty, twenty-five people sitting.”

Sometimes when I’m out on the street it seems to me that people’s faces are like flowers.

In the 1980s, her little community was sought out by people struggling with the AIDS crisis. “I’m living in the Village, I’m a lesbian, and AIDS hits,” she says. “So lots of people came to sit. A lot of men, and people who were sick. I was asked to lead a group at Gay Men’s Health Crisis for people with HIV.”

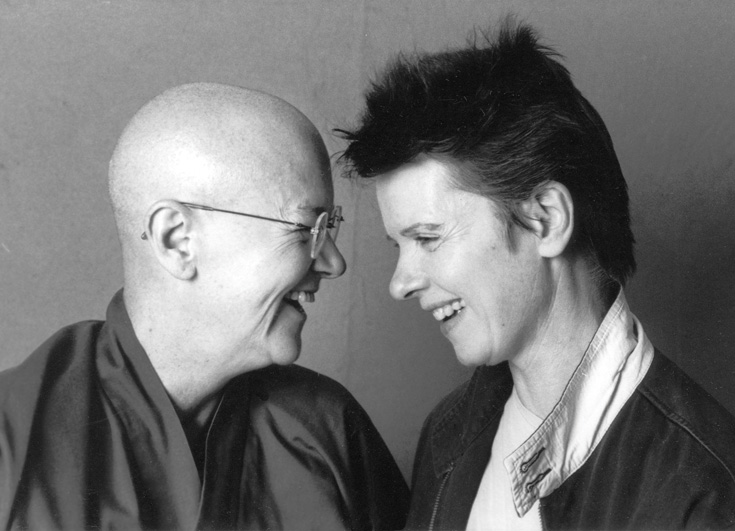

Soon O’Hara’s sitting group outgrew her apartment. In 1986, O’Hara cofounded the Village Zendo with her partner, Barbara Joshin O’Hara. It is described on its website as “a community of people who come together to practice in the Soto Zen tradition. We offer zazen (sitting meditation), one-on-one instruction with a teacher, dharma talks, chanting services, retreats, workshops, and study groups. Our programming emphasizes the myriad ways Zen relates to our daily lives in writing, social action, health and well-being, and the arts, as well as traditional Zen studies.”

The Village Zendo moved into a new space in 2000, but when 9/11 hit, they watched from the windows as injured and terrified people ran up the street away from the World Trade Center. O’Hara says that terrible experience tainted the space in their minds and hearts, and they eventually moved into a new location in Soho, where Village Zendo has been for more than a decade.

“Here we sit quietly, majestically, and then you walk out on the street in New York and, quite frankly, we see a lot of hungry ghosts, people with kind of a desperation,” O’Hara says. “But there’s also a kind of sweetness. Sometimes when I’m out on the street it seems to me that people’s faces are like flowers.”

O’Hara tells of a time she was trying to teach a dharma class over the sounds of a political demonstration on the street below. “Then I said, ‘Let’s just listen to them for a few minutes.’ I think it’s incredibly humanizing to practice here in New York.”

O’Hara says Zen practice is not as in demand as it has been in the past. “Zen nowadays is not the coolest tradition on the block,” she says. “But we feel there should be one place in town where you go to just sit and take a really concerted and disciplined approach to Zen practice. I would say those who practice here tend to be ready to do some serious study.”

The Village Zendo welcomes people of all faiths and has introduced identity groups for practice, such as a people of color group and a people with disabilities group. Sangha members also accompany people to immigration court to offer comfort and support, run a prison dharma group, write weekly letters to people in solitary confinement, and organize street retreats—a practice of living like the homeless that was developed by Roshi Bernie Glassman.

“We live on the streets for five days, sleeping on cardboard or in the subway system,” O’Hara explains. “It’s safe. We’ve never had any problems. We stay together at night, but we’re on our own during the day. We beg for food or money, then go meet people in shelters. We donate all of the money we’re given.”

O’Hara did one street retreat while she was a professor. “I planted myself a couple of blocks from NYU on the sidewalk, begging for money,” she says. “Colleagues and students would walk right past me and not see me—because we don’t want to see tragedy, we don’t want to see failure, or whatever our understanding of homelessness is.

“That was huge for me, because I thought, how much of the world do I choose not to see? How can I open my eyes to the suffering so I can be used? My personal experience is people on the street are just great. They have good stories, and you can sit in a park and talk to somebody and not be afraid. There’s this idea that homeless people are crazy, on drugs, or angry, but actually, most of them just had bad luck.”

The Village Zendo website states that O’Hara’s focus as a Buddhist teacher “is on the expression of Zen through caring, service, and creative response. Her five expressions of Zen form the matrix of study at the Village Zendo: meditation, study, communication, action, and caring.”

“I’m compelled to offer encouragement to people to really express the dharma either in art forms or in social justice work,” O’Hara explains. “It’s not about getting to some holy place in your heart at all; it’s the bodhisattva expression. We’re constantly faced with the suffering that’s in the world. My hope is that people can find a way to express service, compassion, and gratitude all the time.”

O’Hara says her teaching style incorporates her experience as a woman Buddhist teacher, as she is sensitive to power differentials and the damage they can cause. “I think it changes the way communities function when there’s female leadership,” she says. “Male teachers are often the seat of all the knowledge, all the power, all the talk. You don’t see that so much with women teachers.”

York City. Social justice is an important focus of the community. Photo by A. Jesse Jiryu Davis.

O’Hara uses her privilege as someone who was trained by male teachers who considered her an equal to help empower other Buddhist women and correct some of the wrongs of Buddhist history.

“Women are not often written or spoken about in Buddhism,” says O’Hara. “In our community, we started chanting the names of women throughout Buddhist history, and I saw the faces of the women in the room bathed in tears. Seeing their faces is what woke me up to how important this is to many women.

“Now I and other dharma sisters in the Zen tradition have a different attitude toward the texts, the legends, and the stories—a little bit more quizzical, a little bit more ironic. You know, how could they all be men? Come on now. This is a constructed quality of all these texts, and we have to know that. It changes the way we talk about things and it changes our attitudes toward forms and services and hierarchy, the whole power relationship. Everything begins to shift a little bit, I think.”

O’Hara sees why certain types of people are drawn to woman teachers.

“In particular, the kind of man who is drawn to a woman teacher is probably a little different than the kind of man who is drawn to a male teacher,” she says. “I asked some men students why my teaching appeals to them, and most of them said they wanted something that was open to the masculine, yet without the martial quality of traditional Zen. They liked the softer approach I offer, particularly in terms of body work—meditating in a position of ease as opposed to a position of tension, that kind of thing.

If you are having all of your experiences passively, you’re not activating yourself.

“I remember giving a talk about not being heard and not being seen as a woman. After the talk, a man came up to me and said, ‘You know, you’re also talking about me and my life.’ That really helped me to see that in dealing with issues of sexism, racism, homophobia, that kind of thing, we’re talking about everybody’s experience.”

O’Hara says she has seen Western Buddhism become more individualized in the time she’s been practicing. “When I began, there were large groups of practitioners that belonged to different, distinct traditions,” she says. “But because of the popularization of meditation and mindfulness, I think that the ordinary person’s understanding of the various traditions is much less now. I love things to be spread out and popularized, but with that comes a dilution and a superficial understanding. It also brings out people who want to take advantage and use the language just to make money. Is it a good thing or a bad thing? Some of each. The good part is more people are hearing about it. At the same time, we’re losing some of the depth of study that I personally hold sacred.”

O’Hara’s media training also plays into her view of Western dharma. “There is a shift in the way that we take in information,” she says. “So if you’re sitting at home, listening on your computer about meditation, and you’re not actually doing it or practicing it, then it becomes just another cloud of information floating by. There’s this disembodied aspect to digital media that troubles me. I think that has an effect, because if you are having all of your experiences passively, you’re not activating yourself.”

O’Hara feels that one modern contribution to Buddhism has been “more direct social justice work, and the ability to speak about social justice, which many of us have gotten from Jewish, Muslim, and Christian traditions. Turning the other way, the Buddhist view of interdependence, that we’re not these separate beings, has seeped into many Western discussions. This has helped elevate the value of compassion.”

O’Hara says she had an experience on an airplane that put things into perspective for her. “I was flying over the Midwest,” she says, “and I looked out and saw this little house and all this land around it. Then I saw this other little house and all this land around it. And I thought, ‘I can understand why they think they’re independent. They don’t see that all that land is one. They don’t see that we’re all interconnected, that we’re sharing the air and we’re sharing this earth. They just see it in these little pieces.’

“That was an insight. I try to have compassion for those who don’t agree with my view. That’s our job.”