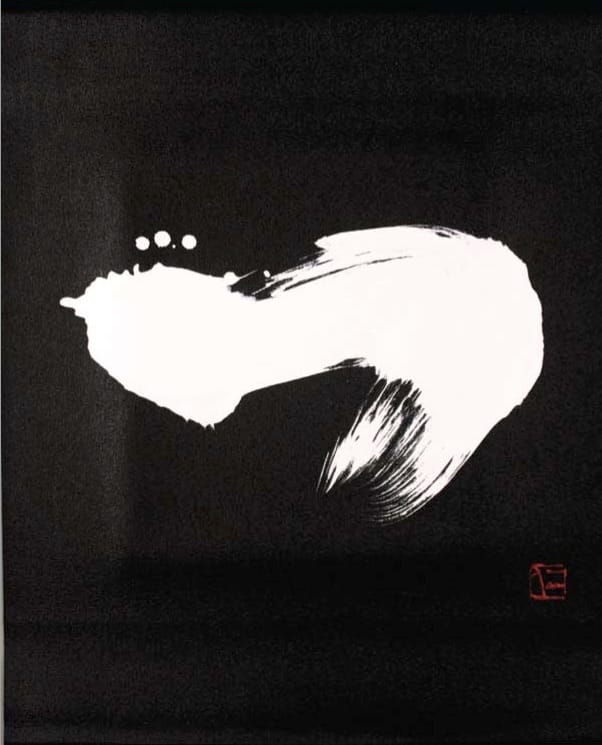

Meditation (zazen) can be restful and enjoyable, according to Dogen. Its state (samadhi) can be like an ocean that is serene and yet dynamic. Its field can be as vast as springtime, which encompasses all of its flowers, birds, and mountain colors. Being in spring, we hear the sound of a valley stream or become a plum blossom swirling in the wind.

Dogen’s poetic descriptions may seem contrary to our usual meditation experience. Often we are troubled with physical pain and sleepiness; our mind may be scattered, and our daily concerns continue to preoccupy us. We may feel that we have had a bad meditation. Dogen, however, seems to show no interest in these specific issues. He simply speaks of the magnificence of meditation and asserts that we can experience luminosity as soon as we start to meditate.

What we think we experience in meditation may be different from what we actually experience. What, then, do we experience? How do we recognize our deep experience and apply it to our daily lives? These are some of the questions Dogen addresses.

If we were to summarize Dogen’s teaching in one word, it might be “nonseparation.” In meditation, the body experiences itself as not separate from the mind. The subject becomes not apart from the object.

While our thinking is often limited to the notion of “I,” which is occupied by “my” body, “my” mind, and “my” situation, Dogen teaches that we can become selfless in meditation. Then, we are no longer confined by our self-centered worldview and a dominating sense of possessions. Only when we become transparent and let all things speak for themselves can their voices be heard and their true forms appear.

As we calm down and move away from the usual mode of physical and mental activities, we often have a good idea or even, at times, an extraordinary insight during meditation. However, this is only a beginning stage. If we go further, we may experience a dissolving of the notion of the self. Dogen describes such an experience of his own at the climactic moment of his study as “dropping away body and mind.”

Beyond Space and Time

The distance from here to there is no longer concrete. A meditator walks on the top of a high mountain and swims deep in the ocean, not only becoming an awakened one but also identifying with a fighting spirit. A person who bows becomes one with the person who is bowed to.

Sizes become free of sizes. The depth of a dewdrop is the height of the moon. The entire world is found in a minute particle. Extremely large becomes extremely small, and vice versa. Here is another view of reality distinct from our usual way of seeing.

It is not that duality stops existing or functioning; the small is still small and the large is still large. The body remains the body and the mind remains the mind. Without discerning the differences between things, we could not conduct even the simplest task of our daily lives. And yet, in meditation the distinctions seem to dissolve and lose their usual significance. Dogen calls this kind of nondualistic experience nirvana, which exists at each moment of meditation.

Dogen is perhaps the only Zen master in the ancient world who elucidated in detail the paradox of time. For him, time is not separate from existence; time is being.

Certainly, there is the passage of time marked by the movement of the sun or the clock that always manifests in one direction, from the past, to the present, to the future. On the other hand, in some cases we feel that time flies, and in other cases it moves slowly or almost stands still.

In meditation, according to Dogen, time is multidirectional: Yesterday flows into today, and today flows into yesterday; today flows into tomorrow, and tomorrow flows into today. Today also flows into today. Time flies, yet it does not fly away. This moment, which is inclusive of all times, is timeless.

Further, time is not apart from the one who experiences it: time is the self. Time flows in “I,” and “I” makes the time flow. It is selfless “I” that makes time full and complete.

Beyond Life and Death

Time is also life. In the same manner, time is death. Like other Zen teachers, Dogen repeatedly poses an urgent existential question: realizing the brevity of our life, we need to clarify the essential meaning of life and death.

Life and death are often called “birth and death” in Buddhism, based on the understanding that we are born and die innumerable times moment by moment. Meditation is a way to become familiar with life and death. If we realize that we keep on being born and dying all the time, we become intimate with death as well as life. Thus, we may be better prepared for the moment of our departure from this world than we would be otherwise; and this, in turn, reduces our fear of dying.

For Dogen, each moment of our life can be a complete and all-inclusive experience of life. The life of “I” is not separable from the life of the whole—the life of all beings. In the same way, death is a complete and all-inclusive experience.

When we fully live life and fully die death, life is not exclusive of death; death is not exclusive of life. Then life and death are no longer plural but singular as life-and-death or birth-and-death.

It is a dilemma of life: we all die, and yet, avoiding death is no solution. When we thoroughly face death, death becomes “beyond death.” Dogen tells us that this is the meaning of “life-and-death” for an awakened person.

Enlightenment and Beyond

The Zen way of going beyond the barrier of dualism is to meditate in full concentration. This is called “just sitting.”

Dogen’s invaluable contribution to clarifying the deep meaning of meditation is his introduction of the concept called the “circle of the way.” It means that each moment of our meditation encompasses all four elements of meditation: aspiration, practice, enlightenment, and nirvana.

“Aspiration” is determination in pursuit of enlightenment. “Practice” is the effort required for actualizing enlightenment. “Enlightenment” is the awakening of truth, the dharma. “Nirvana,” in his case, is the state of profound serenity, in which dualistic thoughts and desires are at rest.

Dogen says that even a moment of meditation by a beginning meditator fully actualizes the unsurpassable realization, whether that is noticed or not. In this way, enlightenment, often regarded as the goal, is itself the path. The path is no other than the goal.

The word “enlightenment,” a translation of the Sanskrit word bodhi (literally, “awakening”) has layers of meaning. Firstly, according to Mahayana sutras, Shakyamuni Buddha said, “I have attained the way simultaneously with all sentient beings on the great Earth.” That is to say that all sentient and insentient beings are illuminated by the Buddha’s original enlightenment and thus carry buddhanature—the potential for or the characteristics of enlightenment. In other words, in the Buddha’s eye, all are equally enlightened and none are separate from the Buddha. However, this does not mean, from the ordinary, dualistic perspective, that all beings become wise and free of delusion.

Secondly, in Dogen’s explanation of the “circle of the way,” all those who practice meditation are fully enlightened. Enlightenment is not separate from practice; enlightenment at each moment is no other than the unsurpassable enlightenment. This aspect may be called the unity of practice–enlightenment or practice–realization. Dogen emphasizes practice that is inseparable from enlightenment as the essential practice of the way of awakened ones—the buddha way. The awareness of enlightenment, however, may not necessarily be recognized by everyone all the time, as it is an experience deeper than one grasped by intellect alone.

Finally, when we practice meditation, we often don’t notice that we are already enlightened, and thus we look for enlightenment somewhere other than in practice. Dogen calls this tendency of separation “great delusion.” This pursuit, however, provides us with the potential for “great enlightenment,” which is a merging of the unconscious practice–enlightenment and conscious understanding.

This enlightenment can happen unexpectedly and dramatically as a body-and-mind experience of the nonseparation of all things, rather than as a theoretical understanding. Such spiritual breakthroughs, sometimes called “seeing through human nature” (kensho in Japanese), may bring forth exuberance. Dogen quotes many such stories of “sudden realization” by ancient Chinese Zen practitioners as cases of study (koans).

However, Dogen discourages his students from striving for breakthroughs, cautioning that this pursuit is based on the notion of a separation between practice and enlightenment. This kind of realization or “attaining the way” takes time and usually follows a series of failed attempts. In regard to this, Dogen says, “… even if you are closely engaged in rigorous practices, you may not hit one mark out of one hundred activities. But by following a teacher or a sutra, you may finally hit a mark. This hitting a mark is due to the missing of one hundred marks in the past; it is the maturing of missing one hundred marks in the past.”

An awakened person, a buddha, is someone who actualizes enlightenment. If enlightenment is nothing separate from practice, it is clear that all those who practice meditation as recommended in Buddhism are buddhas. And those who have experienced and reached deep understanding of the nonseparation of all things are regarded as ones who have attained the way.

However, for Dogen, attaining the way is not the final goal. He encourages practitioners of the buddha way to go beyond buddhas and leave no trace of enlightenment. That is to say, we are not supposed to remain in the realm of nonduality.

Going beyond the boundary of all things is important. It is wisdom, which is the basis of compassion. Only when we identify ourselves with others can we genuinely act with love toward others. At the same time, however, for practical and ethical reasons in our daily activities, we need to maintain the boundaries of self and other. An enlightened person is someone who embodies the deep understanding of nonduality while acting in accordance with ordinary boundaries, not being bound to either realm but acting freely and harmoniously.