Recently, while attending a public teaching by the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Tsoknyi Rinpoche at Wellesley College, I was surprised to hear a term I had only heard within the confines of a long-term cloistered retreat or in the context of esoteric tantric manuals: subtle body. Rinpoche was describing the need for Western students to connect with the body as a way of healing emotionally. “To find balance,” he said, “we need to pay more attention to the body, especially the subtle body.” I found this reference in a very public venue refreshing and practical. There are growing indications that the idea of a subtle body, long embedded in the secret teachings of esoteric traditions, is coming out of hiding.

The subtle body is the subject of a new anthology edited by anthropologists Geoffrey Samuel and Jay Johnston titled Religion and the Subtle Body in Asia and the West. Samuel and Johnston have drawn together fourteen essays, focused on cultures in Asia and Europe, that take as a theme the cultural construction of an alternate subtle substrate of the human body—one that is either superimposed on, or in juxtaposition with, the body of flesh, blood, and bone. They note that while Western understandings of consciousness are predicated on the idea of a Cartesian distinction between mind and body, Eastern systems have long assumed a more integrated model. That said, Samuel and Johnston have solicited scholarship that suggests that the idea of an alternate “subtle” body has not been confined to one region, but rather exists across traditions in Asia and Europe, from Greek religion to Taoism to Buddhism to Sufism. The scholars featured in this anthology also demonstrate the impact of the subtle body model on modern thought, including popular philosophical systems such as Theosophy.

The publication of Religion and the Subtle Body corresponds with a minor surge in academic research into notions of the subtle body, and also into alternative theories of the body more generally, within Indic and Tibetan traditions (David White, Janet Gyatso, Francis Garrett, and Vesna Wallace, for example) and among Buddhist teachers actively exploring the role of the body in meditation (such as Reginald Ray, Peter Levine, Judith Blackstone, and Rose Taylor Goldfield).

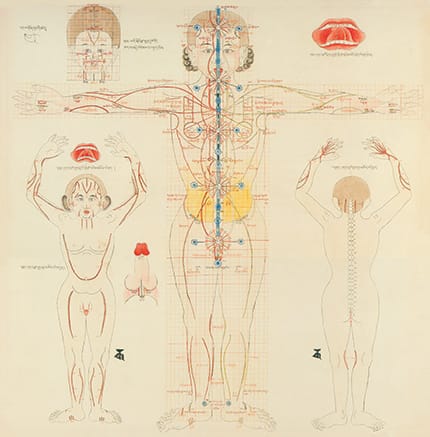

The term “subtle body” is a close translation of a term found in Sanskrit sources, sukshma-sharira, rendered in Tibetan as traway-lu (transliterated phra ba’i lus). According to Samuel, the term’s origins extend back as far as the Indian Taittiriya Upanishad, composed during the fourth to fifth century, which discusses five coexisting bodies: the physical body, the vital breath body, the mental body, the consciousness body, and the bliss body. Samuel tells us that by the eighth century, with the emergence of the Buddhist niruttarayoga tantras, the term had come to refer to a complex subtle physiology that both coexists with, and functions in constant relationship to, the physical body and its cognitive correlate, the mind. This strain of Indian Buddhist tantric literature became very influential in the Himalayan region, where it remains a major part of religious tradition to this day.

Given the close relationship between this subtle physiology and the coarse flesh-and-blood body, it is not surprising that in contemporary Himalayan (or Tibetan) Buddhist practice, the subtle body acts as a kind of bridge between the body and mind. This view can be found dating back to the work of Yangonpa Gyaltsen Pal (1213–1258), a Tibetan yogi and author of one of the earliest Tibetan handbooks describing the subtle body. In his seminal work on this topic, Description of the Hidden Vajra Body, he explains that as an interface between body and mind, the subtle body has elements of the physical, such as form, colors, and structure. But it has elements of the mental as well; like thought and emotions, the subtle body can be reconditioned with focus, training, and intent, and even permanently altered to support a more enlightened state of being.

Echoing a system found in many Buddhist tantras, Yangonpa taught that the activity of bridging body and mind takes place via a tripartite structure of channels (nadi), winds (vayu), and drops (bindu), the key components of the subtle body. These components are interconnected and find expression in their subtle correlates of body, speech, and mind. The channels, as subtle correlates of body, are pathways. The winds, subtle correlates of speech, are energies that move along those pathways. And the drops, which are subtle correlates of mind, are vital essences that are stored in and move throughout various locations of the body.

In tantric theory, specific practices and transmissions involving appropriate attention to these three subtle aspects of being facilitate training and mastery of the movement of energies and vital essences, eventually catalyzing an enlightenment experience that is authentic and irreversible. Hence, this subtle interface between body and mind becomes the key component of liberation: if the subtle body is mastered, the mind can be freed. For that reason, in Buddhist tantric practice, the subtle body takes on a role of supreme importance.

Yangonpa further states that the mechanism for this kind of somatic awakening resides first and foremost in the simplicity of valuing, learning about, and experiencing the subtle body. The subtle body of Buddhist tantric understanding is not subtle merely because it is invisible to the naked eye, but also because it can only be fully known through internal sensory or meditative experience. According to Yangonpa, simply learning a map of the subtle body is not enough. A yogic practitioner must pay attention to the field of the body’s experience, a notion that students of the dharma long accustomed to valorizing the mind may find challenging, though ultimately refreshing. In paying attention to the body’s field of experience, the mind is naturally and immediately involved, but attention is drawn away from thought and becomes immersed in somatic feeling. In this way, the subtle body inhabits an “in between” mode of embodiment, mediating between body and mind.

Our physical body, with its heaviness and self-regulating activity, seems largely out of our control. Similarly, we often experience the mind, with its flightiness and intelligence, as completely unmanageable. The subtle body bridges these two realms—the mental and the physical—by privileging neither body nor mind in isolation, but rather accommodating both as an integrated whole. This whole is the field of somatic experience, as it occurs at the present moment. While the body may not be in our control, the quality of our attention to our experience is, and this is where we begin to enter the world of the subtle body. Here, we find a unique place of entry into a more conscious relationship with both body and mind.

How, then, does one do subtle body practice? This question rests outside the scope of Religion and the Subtle Body, which instead explores the sociocultural and sociohistorical perspectives on the notion of a subtle body. However, we can look to another source—Rose Taylor Goldfield’s Training the Wisdom Body, out this season—for answers. Taylor Goldfield, a student of Khenpo Tsultrim Gyatso, delivers an excellent and accessible handbook for those wishing to directly experience the subtle body. Echoing Yangonpa, she explains that the subtle body is easily experienced when we turn our attention to our lived experience of the body: “We connect with the subtle body when we open to feelings, sensations, and patterns of energy in the physical body.” Taylor Goldfield emphasizes that this connection can also be heightened through yogic practices that increasingly draw our attention to the energetic dimensions of being.

Taylor Goldfield explains that the state of a person’s subtle body is closely connected to his or her emotional health. Her book introduces us to many traditional Buddhist exercises designed to heal and balance the subtle body; even so, she also stresses that exercise in general can also balance the subtle body, pointing to the profound impact that everyday exercise can sometimes have on our emotional well-being. As she puts it: “When we feel anxious or agitated, exercising with vigor is highly beneficial for our subtle body. This is because anxiety often locks itself in the subtle body in a frozen energy pattern. This can occur anywhere in the body but often manifests in the stomach, the heart center, or the throat center. It can be difficult to sit with such a feeling, and moving the body may be more efficacious in easing the stress.” The exercises offered by Taylor Goldfield can help unlock those energy patterns.

This emotional connection can be viewed from another perspective as well. Tsoknyi Rinpoche, in his most recent book, suggests one way to experience the subtle body is simply to notice how emotions play out in our physical body. In any experience of emotion, there is both a thought component and a physical component. An emotion changes our physical experience. If we are angry, we might become flushed and our muscles become tense. To notice this is to enter into relationship with the subtle body. The mechanism by which our body registers the emotion of anger is the movement of energy winds, or vayu. Observing this feeling coursing through our body, we might have a first-time experience of what energy wind really is. Simply bringing attention to this sensation can alter our relationship to the anger as well. While we tend to understand anger in terms of the thoughts that generate and feed it, we could just as well experience anger as a subtle energetic event passing through the subtle body. Anger now becomes more like a passing storm, a natural and simple event.

In Religion and the Subtle Body, we discover that this connection between health and the subtle body is currently being explored in the American scientific community. Alejandro Chaoul, a professor at a medical center in Texas and a practitioner of Tibetan yogas, heads an NIH-funded research study that is examining the effects of Tibetan subtle body practices on the outcomes for breast cancer patients. The hypothesis of the study is that teaching cancer patients the movements, breathing exercises, and subtle body visualizations found in the Tibetan yogic traditions can reduce stress and improve quality of life. By extension, according to Chaoul, these traditional practices can help people become “more sensitive to the subtle aspects of breath, body, and mind,” which helps them to better manage both stress and pain. He states that learning visualizations of subtle tantric physiology, when combined with breathing and exercises, brings the subtle body naturally into balance.

Yangonpa, writing in the thirteenth century, suggests that there are reasons these yogic practices, passed down for hundreds of years, work to bring the subtle body into balance. He suggests that these methods can potentially catalyze a collapse of the divisions we make between body and mind, and through this collapse, we experience freedom. But we must first see the limitations of dividing ourselves into parts. In Yangonpa’s view, the subtle body is mastered by intentionally recognizing the radical integration of the dyads of body and mind, winds and mind, and body, speech, and mind. He says that while we might pay attention to components of the subtle body such as “energy center” (chakra), “energy wind” (vayu), and “channel” (nadi), the key to bringing the subtle body into alignment rests in seeing that all the components of our embodied experience are blended inseparably. When this inseparability moves from being a thought to being an experience, that is enlightenment.

Yangonpa, and his predecessor Naropa, focused on the inseparability of the energy winds and mind. If we can bring mind into a radical union with energy winds, the theory goes, that alone liberates. Even if we are not now recipients of the esoteric methods to do this, Yangonpa’s idea of inseparability is eminently practical. Whether we become enlightened or not, we might naturally discover a direct experience of the subtle body—not a conceptualization of the body, but rather a “felt” body that includes our entire sensory field.

The body seems to be coming of age in Buddhist practice in America, and we may do well to pay close attention to the shifting sands. Many of us relate to this body as a heavy and inconvenient vessel, the reason we are ill, sleepy, distracted, or uncomfortable. But the tantric traditions provide us with a possibility that the body is more than a heavy and inconvenient truth. As the Hevjara Tantra famously states, “Great wisdom abides in the body.” In tantric view, the body is not only the door to wisdom, it is wisdom itself.

Religion and the Subtle Body provides an anthropological and sociohistorical perspective on the subtle body; Training the Wisdom Body invites readers to experience the subtle body for themselves. The traditions and practices introduced by these two new publications offer the possibility that the body itself is spontaneously sacred, expressing the qualities of awakening, every day, whether we know it or not. As human beings, we are challenged by these works to question previous assumptions and constructions we have made about our own bodies. And as practitioners, we are invited to view the body as the key to our own enlightenment.