I don’t know what I am expecting. As we exit the van we are welcomed only by a chilly winter wind blowing down Bear Ear Mountain. The lonely mountain, just a few hundred feet high, conveys a sad sense that something important has been forgotten here. Naked land stretches for miles in all directions.

We’re about an hour’s drive west of Luoyang, China’s most ancient capital, and a few miles off the new Luoyang—Xian expressway. We left the highway at an exit called Kwan Yin Hall, although no hall — and no Kwan Yin — were to be seen. A short drive south brought Bear Ear Mountain and the site of Kong Xiang (“Empty Form”) Temple, Bodhidharma’s final resting place, into view.

My traveling companion is Red Pine, the well-known writer and translator of Chinese texts. We’re looking for Bodhidharma’s grave, but we have little idea of its exact location. I’ve gleaned only a few clues — from the Zen Lamp Records and a statement in Keizan’s Transmission of Light — that it was at a place called Bear Ear Mountain. We are also keen to find out more about the second Chinese Zen ancestor, Huike. But we are even more in the dark about him. All we know is that he lived and taught in the city of Yedu, near the site of modern Handan City in Hebei province.

A short walk from the road reveals a weathered stupa, the same color as the brown earth that surrounds it. Our guide tells us that it is a six-hundred-year-old marker of the place where Bodhidharma’s original stupa once stood. It appears empty and neglected, too frail to withstand the wind and dust of North China’s plain much longer. Red Pine and I circumambulate and bow to the small structure. The wind blows stronger, as if to argue that what we are honoring is long gone.

Not long before our visit, a group of Japanese Zen Buddhists had sought and found this important place. A photo shows them consecrating the ground around the old stupa, and now a new temple is slowly growing here, its boundaries marked by a whitewashed stone wall that snakes around the area in a wide arc.

Empty Form Temple was built long before Bodhidharma’s arrival here. For a long time it was called Ding Lin (“Meditation Forest”). The Tang emperor Xuan Zong personally renamed it Kong Xiang (“Empty Form”) to commemorate Bodhidharma and his teachings, proof of their renown more than two hundred years after his death in 535.

I take in the mountain view from Bodhidharma’s stupa and remember reading that the place once teemed with vegetation and wildlife. Ancient visitors delighted in a long-gone nature park that now exists only in my mind. Not long ago, workers here uncovered a stone stele record from the temple grounds that was inscribed about the year 672. This record says the temple once covered a vast expanse with many square miles of land. Looking around me, I consider how the true-nature beauty of the landscape might be recreated someday to delight future pilgrims.

Near Bodhidharma’s stupa, four round-topped stone monuments rise from the dusty slope. The guide explains that they are tenth-century reproductions of originals praising Bodhidharma. It is said that Emperor Wu Di, whose famous meeting with Bodhidharma is recorded in the Blue Cliff Record, wrote the inscription for one of the original monuments. Emperor Wu reportedly commissioned one monument here and another at Huike’s grave, direct evidence not only that Bodhidharma existed but also that he was honored in his own age.

While scholars debate the actual history of the period, tradition honors Bodhidharma as the first in the line of teachers of Chinese Zen. In Chinese, the term “Zen master” also means “Dhyana master,” and there was no shortage of these in China before Bodhidharma arrived from India. Many Buddhist priests held that title, among them an Indian Buddhist monk who presided as the first abbot of Shao Lin Temple after construction was finished in 496. A few years later, Bodhidharma arrived at Shao Lin Temple, where he undertook his famous nine-year cave meditation.

With many masters predating him, why is Bodhidharma called the First Ancestor? And why does his life hold great fascination for many in China, Japan, and now here in the West?

Chinese Zen before Bodhidharma consisted of prescribed meditation practices. The change that Bodhidharma symbolizes emerged in fifth-century China with new Buddhist scriptures that had made their way from India. These sutras, part of the Fa-Xiang (“Consciousness Only”) school of Buddhism (also called Yogacara) established by the famed Indian Buddhists Asangha and his stepbrother Vasubandhu, reached the height of their influence at about that time. In light of the new scriptures, Zen practice was transformed, becoming a sort of stepchild of the Consciousness Only school. Bodhidharma apparently emphasized a particular scripture of this school called the Lankavatara Sutra.

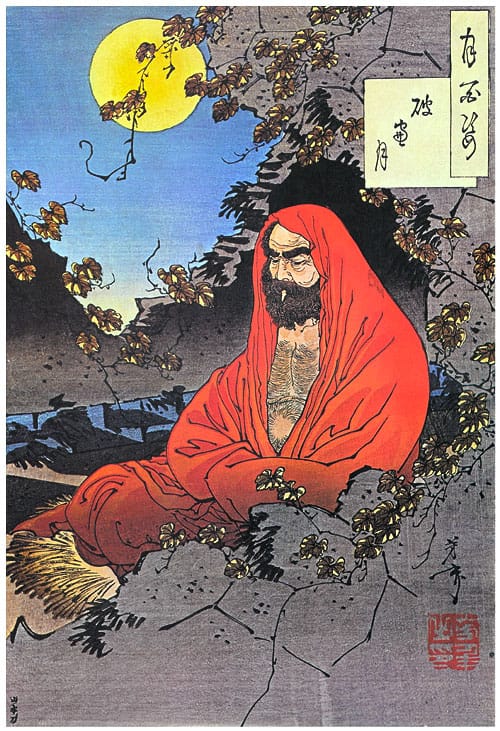

Bodhidharma’s renown comes from his teaching, “Point directly at the human mind, see its nature, and become Buddha,” a dictum long regarded as the taproot of Zen. Zen teachers from early times until now have credited this phrase to Bodhidharma. We find it on hundreds of paintings of him by the famous seventeenth-century Japanese teacher, Hakuin. While what is left of his work does not contain this exact phrase, the writing attributed to Bodhidharma is full of teachings on the importance of observing the nature of mind.

Only two teaching generations after Bodhidharma, his message is said to have been carried to Vietnam by an Indian monk named Vinitaruci, a student of the third Chinese Zen ancestor, Sengcan. Zen teachings thereafter spread throughout China and were established in Korea by the ninth century. Although we usually associate Zen with Japan, it did not take solid root in that country until seven hundred years after Bodhidharma lived in China.

How certain are we that teachings and writings attributed to Bodhidharma actually came from him? Before the establishment of Shao Lin Temple, its location was called Shao Shi, or “Few Dwellings.” One work usually credited to Bodhidharma is Record of Few Dwellings, which outlines six gates to liberation, including his well-known “Outline of Practice.” The reference to the place name predating Shao Lin Temple tells us that the text was written while the old name was still in use, perhaps while Bodhidharma was staying there. For this reason and others, some scholars think that of all the texts attributed to Bodhidharma, this one is the most likely to have been written by him.

Some of the texts attributed to Bodhidharma and other early Zen teachers that emphasize teachings about the nature of mind have yet to be translated into English or are not widely known. Whether or not such texts were in fact written by Bodhidharma, they seem to reflect a widespread perception of his teachings. In content and style, they differ from the later Zen Lamp Records, where the most famous Zen stories are found. They differ even more from the Blue Cliff Record and Wumenguan (Mumonkan) texts, well known in the West, which came from a

One of the oldest records about the Second Ancestor, Huike, is a stone memorial inscribed about the year 634 by a Buddhist priest named Falin. It praises him with the following verse:

Great teacher!

Though form was your vessel,

Mind was your virtue!

Always loyal to Buddha,

Because you reached this [teaching],

you reached everywhere,

For dharma you gave your arm,

Not retreating, you remained steadfast

with the truth

That all mind is Buddha mind, all affairs

are Buddha’s affairs,

In the belabored world this always shines,

Resplendent through the ages.

To start our search for Huike, Red Pine and I meet at Cypress Grove Monastery, the ancient dharma seat of Zen master Zhaozhou (“Joshu” in Japanese) near the city of Shijiazhuang, not far from where Huike lived in Hebei province. We both frequent this famous monastery where many famous events occurred, including the meeting that gave rise to Zhaozhou’s Mu (Chinese: Wu) koan. It is run by our good friend Abbot Minghai (“Bright Sea”). Shortly after our arrival, fortune smiles when a resident monk tells us about a nearby lay practitioner-scholar who has thoroughly researched the life of the Second Ancestor. This is welcome news. The few Western accounts of the Second Ancestor that I’ve read doubt Huike’s existence or claim that his fate was unknown. I immediately invite the scholar, Mr. Gao Shita, to come to our hotel that evening.

Mr. Gao is most responsive and helpful and provides us with a map showing the way to Huike’s ancient dharma seat, as well as his burial place. It surprises me to learn that, despite the obscurity of Huike’s life, both his dharma seat and his burial pagoda are located at temples in the county of Cheng An, not far from Handan City, near a fair-sized town called Second Ancestor’s Village.

The next day, after catching a train to Handan City, we hire a taxi for the trip into the countryside. The growing season is just beginning. Peasant farmers on both sides of the road work their ancient fields beneath a bright, cold sun. Before long, a sign above the highway directs us to an unpaved road leading to the outskirts of Second Ancestor’s Village.

The narrow streets of the town wind their way around decaying adobe homes and shops. Except for some toddlers dressed in brightly colored jackets, the inhabitants match the bland and dispirited display of their surroundings. The taxi driver asks directions from a man on a shaky-looking bicycle, but following his instructions leads us deep into a crowded maze of lanes that ends in a dusty street market. After a few more attempts to get through the village, we double back to take a northern route around the town. Finally, we arrive at the temple.

Yuanfu Temple was once grand; a local legend says that two large iron cuckoos perched in the rafters of its great buddha hall. And even though it was located near a dusty riverbed, the area around the temple was said to be miraculously clear, while nearby areas were tormented by constantly blowing dust. During the Cultural Revolution the temple was closed and three new occupants were installed: a sawmill, a cement factory, and a museum dedicated to revolutionary martyrs. Now everything but a portion of the museum has closed, and residents of the remaining buildings watch our explorations with bemused curiosity.

All that remains from the original temple are some small stone monuments. A new buddha hall is nearing completion, but there are no other temple buildings. Inside the buddha hall, some new buddha statues await unveiling, facing out the open front to the most striking feature of the area, a large mound of earth buttressed with a stone wall. According to history, both Bodhidharma and Huike expounded the newly arrived Zen dharma from this flat-topped knoll, known since ancient times as Dharma Expounding Terrace.

Not far from Yuanfu Temple, at the north edge of the village, we encounter the remains of Kuangjiao Temple, Huike’s final resting place. Entering a high gate, we discover a broad patch of dusty earth and brush covering several acres, the front surrounded by masonry walls. At first glance there are no buildings; the whole expanse seems defined by desolation, with collapsed pillars and old statuary jutting from the earth haphazardly. Near the front of the site, a craterlike hole marks the spot where Huike’s burial pagoda once stood. Its bricks long ago hauled away to construct farmers’ huts and privies, only litter and broken incense urns and other half-relics remain.

A hundred yards or so to the rear, at the back of the site, nobly sit big, white, alabaster buddha statues of incongruously recent creation, appearing to wait patiently for a new hall to protect them from the elements. Now we notice the only real building on the site, a contemporary brick structure that looks good for storage. On closer inspection, we find it half-occupied by a resident caretaker monk who greets us cheerfully. His name, appropriately, is Guole (“Nation’s Happiness”).

Guole explains that this is indeed the place where the Second Ancestor’s remains were interred after his execution. According to the records, his teaching of Bodhidharma’s Zen angered the entrenched Buddhist establishment. They denounced his heresy to the king, and Huike was indicted. Convicted and condemned to death, he thus became not only the Second Ancestor but also the first martyr of Chinese Zen.

As if in passing, Guole asks if we’d like to see the Second Ancestor’s burial urn. We follow him to a storeroom where the broken burial vessel of Huike’s sacred relics rests among empty grain bags, bottles, and other litter. Guole explains that the relics are now held safely in a smaller urn kept by the local historical society. Next to the urn we find a small cracked stone stele, which I photograph. When I translate it later, I find it to be an eleventh-century memorial acknowledging the generosity of patrons who contributed to the cost of repairs to the temple after it was damaged during a period of warfare.

In the Zen Lamp Records, we find the story of Bodhidharma’s transmission of his dharma on mind to the Second Ancestor, which took place by a mountain cave near Shao Lin Temple. Huike is said to have waited in the snow for Bodhidharma to emerge from the cave. Some versions of the story claim that he cut off his left arm to demonstrate his earnestness. Here is the critical exchange that transpired when Bodhidharma finally emerged to meet him:

Huike: “Please teach me the dharma seal of all the buddhas.”

Bodhidharma: “The dharma seal of all the buddhas cannot be obtained from someone else.”

Huike: “My mind is distressed. Please pacify it [with your teaching].”

Bodhidharma: “Present me your mind and I will pacify it.”

Huike: “I’ve searched for my mind, but I can’t find it.”

Bodhidharma: “There. I’ve pacified it.”

This story, which was not meant to be cute, reveals an important aspect of the nature of mind. Zen emphasizes that our mind, indeed our ungraspable “self,” is not to be found in our body or brain. This is the “big mind” that Zen and Tibetan Buddhist teachers love to talk about. It is also sometimes called the “mind of all beings,” “true monk’s eye,” and, most of all, “the treasury of the true dharma eye.” The latter name was used throughout China’s Zen history, although it is most often associated with the work of the Japanese teacher Eihei Dogen, many centuries later. The nature of this “big mind” is described throughout the Zen Lamp Records. It is what the old Zen master Huangbo said “is always manifested,” and comprises, in Dogen’s words, the “myriad things that come forth” to be our true self.

Many students, and even some teachers, consider the point of Zen practice to understand the nature of reality, but that is not so. Such a practice is unrealistic and can lead to confusion and difficulty for students. In his instruction, “Point directly at the human mind, see its nature, and become Buddha,” Bodhidharma makes the key point that rather than look for ultimate reality, we should instead observe our ultimate nature, the nature of mind. This is simply what is happening, or, to use the traditional term, “thusness.” Bodhidharma does not set forth a doctrine of belief or even, ultimately, a defined method of practice. He just points directly at the human mind and asks us to see what’s happening. Our meditation is the act of observing mind.

In China, there are a variety of places where Bodhidharma is said to have lived and taught. At least two temples in Guangzhou (Canton) are historically connected with him, including Hualin Temple, said to be located near the place where, according to legend, he came ashore after arriving from India. There you can see the remains of an ancient well, located where Bodhidharma once pointed at the ground in a shellfish bed and said, “There is gold there!” Some greedy locals dug a hole to find the gold, but instead they found a sweet spring flowing with miraculously fresh water in an otherwise brackish area. Other places related to Bodhidharma include a temple he is said to have established in Anwei province, plus the place where he is said to have crossed the Yangtse River. A legend that claims he crossed the waters on a “single reed” may have been derived from the name of the place where he is said to have crossed, “Reed.”

Upon his death, Bodhidharma’s remains were interred in a burial chamber at the Empty Form Temple. A legend says that soon thereafter a Chinese man named Song Yun, who was returning from India, passed Bodhidharma on the road, walking in the other direction. He noted that Bodhidharma was wearing only one sandal. Upon hearing this report, the emperor ordered Bodhidharma’s crypt to be opened. His remains were not there. There was nothing to be found but a single sandal. That explains the last line of a verse discovered on a stone stele dated 538, unearthed at the temple, which is also engraved with a likeness of Bodhidharma:

Sailing the sea,

He came from the West with intention,

In Jinling his words not comprehended,

He practiced viewing a wall at Shao Lin,

And left one sandal at Bear Ear Mountain.

When the Emperor Xuan Zong declared in 758 that the temple would thereafter be known as Empty Form (Kong Xiang), he knew that the words had a double meaning. The Chinese words kong xiang sound like the words that mean “empty chamber.” Bodhidharma’s teaching on emptiness by no means ended with his death.

Since our visit, the Empty Form Temple on Bear Ear Mountain has continued to develop. During a one-day visit there in 2004, I witnessed a large truckload of local believers arrive to participate in late-afternoon services in the Buddha Hall. Red Pine more recently revisited the temple, conducting interviews to be included in a forthcoming book. He reports that more new buildings have appeared, and the old stupa has been repaired and steadied.