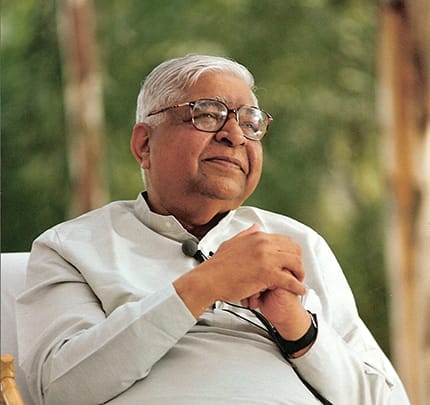

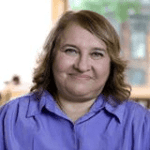

With his famed ten-day vipassana retreats, S.N. Goenka, in the lineage of Ledi Sayadaw, brought the method of insight meditation to modern-day people from all walks of life. Sharon Salzberg, one of his early American students, remembers this remarkable teacher.

I arrived in Bodhgaya, India, in January of 1971, ready to enter an intensive ten-day retreat and learn how to meditate. The retreat was led by S.N. Goenka, who had left his home in Burma to come to India to visit his mother. My introduction to meditation and the living tradition of Buddhism, therefore, came through a layman— a very successful businessman, married with five children. I didn’t know at the time that this was in any way unusual or distinctive in a tradition where monks played such a powerful role in scholarship and transmission, and through the years, Goenka-ji’s work made it seem natural and accepted.

It was amazing to be practicing in Bodhgaya, the place where the Buddha himself had attained enlightenment. Being in that environment brought home the teaching that the Buddha was a real person, awakened through the force of his own efforts. His humanness, as well as his enlightenment, was palpable. This was the landscape he walked through. These were the flora and fauna he encountered. Here was the place he ate milk rice to fortify his body for meditation. And here was where he sat, sheltered by a tree and recognized as worthy by the trembling of the earth.

The closeness and the humanity of the Buddha and the human pursuits and problems of Goenka-ji (he began meditation practice to ease his severe migraines, and he often described his earlier temper) brought the teachings alive for me with a vivid sense of immediacy and connection. It felt as if there was a current of energy running from the Buddha through time to Goenka-ji, and on to all of us. It was a lineage of actual people, with questions and worries and the determination to break free from suffering. It was the lineage of a path, direct and doable, right here and now, not just abstract or theoretical.

Goenka-ji strongly emphasized method, which in the end makes the student quite independent. The method, if diligently applied, will bring balance. If ardently practiced, it will set the stage for transformation. If remembered and returned to, it is a life raft in stormy seas. The method is like a fractal of the entire path; it’s how we can relate to all of the changing conditions of this very moment without being caught by them.

Goenka-ji stayed in Bodhgaya to teach several more retreats in a row, and many of us remained as well. During the third or fourth retreat, Goenka-ji’s beloved teacher in Burma, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, died. It was a strange day. As Goenka-ji brought us together and intoned, “The light has gone out in Burma” (confusing many people, who at first thought it was a problem with the electricity), a stray candle flame leapt up and set fire to a thangka on the wall.

In the days that followed, we entered an alternative reality together. Goenka-ji narrated the cremation point by point, as though we were there: “Now they are putting his body on the funeral pyre. Now…” And I saw something for the first time, something that I’ve seen several times since—what can happen when a teacher’s teacher dies and the newly blown hole in their heart gets filled with the late teacher’s grace, power, and wisdom.

Now, after a lifetime of service to the dharma, Goenka-ji himself has died. He leaves behind a legacy of thousands of students in centers around the world. And he leaves in our hands both an amazing explication of a method and the vital sense, for laypeople, of the possibility of liberation. May his influence, through all of these vehicles, continue and flourish.