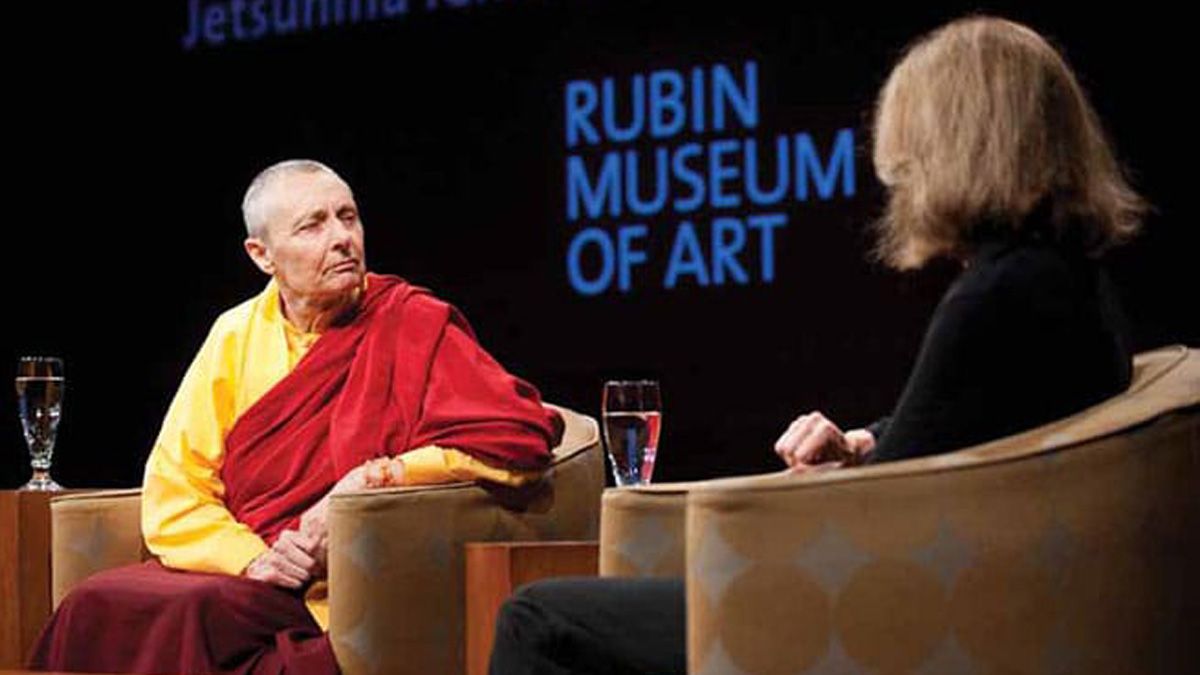

Gloria Steinem: In reading about your life, I’ve been astounded by the degree to which we share certain parallels. We both had mothers who were very supportive of us and also very interested in spirituality. My mother was a theosophist. And so were both of my grandmothers. We both went to India, though in very different ways. I went to India for a couple of years after I graduated from college, mainly because I was trying not to get married.

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo: I am also very grateful to my mother. She was an extraordinary woman. More and more, as I age, I look back and remember her responses to very difficult situations and how skillful she was. We were spiritualists—with séances every week in our house—and I’m very grateful for that because death and what comes afterward was an everyday topic of conversation.

Steinem: You were interested in Asia at a young age, drawn to individual people who came from Asia and drawn aesthetically to it.

Palmo: Yes. I grew up in London and sometimes my mother would take me to Chinatown just so I could see some Asian people. Later I went to work at the School of Oriental and African Studies at London University, and there were so many people from so many different countries, all interested in really interesting things.

Steinem: I think the theosophy in my life drew me to earlier, pre-patriarchal traditions—Native American traditions, the Dalits in India, and later on the Khwe and the San in South Africa. Looking back, because theosophy was so woman-led and so egalitarian, I think I was unconsciously drawn in that direction. Now we’re both engaged in the same thing: we’re trying to include the female half of the globe. But you were incredibly intrepid in going into a male tradition.

Palmo: Quite honestly, I didn’t realize what I was getting myself into. My father died when I was two years old, so I was brought up by my mother and an elder brother. My mother was always a very strong lady, so I never missed having a father. The dynamics of fathers and mothers didn’t play in my life. In India, when I became a nun, I was in a society where monks were the establishment. Since I wasn’t a monk or a layperson, I didn’t really belong anywhere.

At first, I thought that was the problem. Then, in the seventies, I remember coming over the mountain pass to a place called Manali. Somebody had this big book of articles on feminism. I had never heard the word before. I remember just sitting there reading article after article, with everybody laughing at me. But for me it was like suddenly drinking after having been in a desert.

Steinem: That was my sensation, too. Suddenly I thought: I’m not crazy, the system is crazy.

Palmo: Exactly. For me that was a huge revelation. I wasn’t alone. It wasn’t just my situation.

Steinem: That’s such a universal revelation for females of all groups and races and ethnicities who have been in a situation of invisibility.

Palmo: It’s like waking up. That’s how it really is.

Steinem: The ultimate goal of coming together is always the same, I think. Some of us tried to establish a female-honoring tradition as a preparation for coming together, and some of us tried to transform and integrate from within. You stuck with it all by yourself— that is so extraordinary to me.

Palmo: One has no choice.

Steinem: But you did have a choice.

Palmo: Well, it didn’t seem like a choice at the time.

Steinem: You didn’t have a choice between going home and twelve years of meditating in a cave— three of them in strict retreat?

Palmo: Oh, but that was the best part. You know, the lonely times in my life were when I was the only nun surrounded by monks and laypeople. I didn’t belong anywhere. Plus, I was a foreigner. That was very, very lonely. I remember often going home at night and crying. I had to eat by myself, and I lived by myself. But I was working for my lama, so that was the one thing that kept me there.

I desperately wanted to understand Buddhism and practice, and the monks didn’t know how to teach me. And since I was female, they didn’t think it was important to teach me. I’m not trying to whine, honestly. But I remember that this American scholar came and wanted to study for his Ph.D. He wasn’t a Buddhist, and yet they gave him hours and hours every day. They taught him so much, which later he put into his thesis, which became a book. So in one year he learned far more than I ever learned in all the forty years I’ve been with that community. And he wasn’t even going to do the practice. He just wanted to get his doctorate. I remember feeling, why? Here I had given up everything for the dharma, yet they didn’t take me seriously, in the way they took him seriously.

Steinem: And now you are so clearly creating for other women, especially young women, what you didn’t have.

Palmo: When I started the nunnery, one of the lamas said, “You’re very lucky because we have to reestablish in India and Nepal more or less what we had in Tibet. We’re very much bound by traditions. Everybody wants to repeat how it was before. But you are starting something new, so you can do anything you want. Just think it out very carefully because once you start, it’s difficult to change.” So I sat down and thought about exactly what you’re saying: If I were starting out as a new nun now, how would I like to be trained? What would I like to be given? And that’s how I worked out the program, so I could give them what I never had.

Steinem: There are things that seem to be common to patriarchal traditions. One, they’re body denying, and two, a priesthood interprets rather than there being a direct experience. And those two things, maybe because of theosophy and because of those other pre-patriarchal religions or spiritualities, I find really hard. Palmo: In Buddhism, you mean?

Steinem: Yes.

Palmo: Oh, I don’t think it’s body denying. When we ask these girls, teenage girls, why they want to become nuns, they often say, “I look at my mother, my aunt, my older sisters—I don’t want that life. I want to do something really meaningful with my life; I want to benefit myself and benefit others by study and by practice.”

You might think being a nun is very difficult and restrictive, but for them, ironically, it’s actually freedom from the alternative, which would be to get married, have a child every other year, work in the fields, work in the home, take care of their aged families, often while married to someone who drinks and comes back and beats them. Especially nowadays, when they can be educated and do long-term retreat, this is an incredible opportunity for them to discover who they really are and do what they really want to do.

Steinem: That makes total sense to me, just as it does when a young woman becomes a Catholic nun, because her alternatives are exactly as you describe. But what if there were the alternative of a spirituality that was directly connected to nature, without a priesthood? For instance, in some Native American and ancient languages, there are no gender-specific pronouns. The tradition could be one of a very direct connection to nature and a balance between males and females.

Palmo: Buddhism itself is not especially patriarchal. The problem is that the societies in which it developed are patriarchal. Our innate potential to become liberated is the same, male or female. When we’re sitting and practicing, or when we’re not acting out our gender roles, where is male? Where is female? The problem is that the males in any society were the ones who were most educated, so they wrote the books and had the voice. And they wrote the books from their own perspective, naturally, so women were reading something that had already been written from the male perspective.

Steinem: I agree, except that for most of human history there wasn’t any patriarchy. James Henry Breasted, an Egyptologist, says that monotheism is but imperialism in religion. There was a withdrawal of god from nature and from women, which one can see physically on a Nile trip. Have you ever gone on that Nile trip?

Palmo: Yes, I have.

Steinem: You can see, in the representations of butterflies and men and women and so on in papyrus, that with each thousand years, there is more and more withdrawal—the goddess has a son and no daughter and the god gets bigger. You can sort of see the patriarchy evolving. But that’s relatively recent in human history.

Palmo: Yes, that’s true, and in the established religions, the ones that are here today, that’s been apparent, hasn’t it?

Steinem: Yes.

Palmo: What I want to ask you, Gloria, really truly, is why this happened? Women are extremely intelligent, and in Buddhism they are the nature of wisdom, actually. Men are compassion, women are wisdom. Women are extremely intelligent; they are extremely capable. A very obvious example is at our building sites in India, where the women are carrying the bricks and so forth and the men are doing their stonework. At the end of the day, the women go home, and do the cooking and the cleaning and take care of the kids. The men just hang around the fire, smoking their bidis and drinking. If the women weren’t doing this work, where would the men be?

Women are very strong, obviously. They have all the qualities they need. So how is it that in recent history, throughout most of the known world, women have been in this position of being subjected? Why? Is it because we don’t stand together? We don’t respect each other? We don’t respect ourselves? What’s the fundamental reason, do you think?

Steinem: Oppressive systems don’t work unless they’re internalized, and clearly ideas of inferiority are internalized in us. The movement is about talking to each other and discovering that’s not true. But as to the cause, it really was about controlling reproduction, and women’s bodies are the means of reproduction. To determine ownership of children, you have to restrict the freedom of women, which is the origin of various systems of marriage. You restrict the women of the socalled better group and exploit the bodies of the women of the other group. This happened very systematically with the advent of patriarchy.

Gradually, the necessity of controlling reproduction and therefore controlling women’s bodies forced women to have children they didn’t want. When I talked to San women in the Kalahari Desert, it was apparent that they always understood contraception, how to space pregnancies and control their own fertility. In Europe, healers and witches were killed because they taught contraception, which gave women the power to control their own bodies. Eventually Europe became overpopulated, and that led to colonialism and imperialism and racism. And now I think we’re all trying to reverse it; that’s why reproductive freedom as a basic right is so important to women. It’s the single greatest determinant of whether we’re healthy or not, how long we live, whether we’re educated or not. Reproductive freedom is the way of undoing, starting the progression, going back the other way.

Palmo: So then being nuns is excellent.

Steinem: Being nuns is excellent. We need women to be able to choose whether to have one child or four children. And the amazing thing is that when you allow women to do that, the population rate comes out just a little above replacement level, which is where it’s supposed to be. Among the principles of the pre-patriarchal cultures was that there always had to be more adults than children, because otherwise children can’t be properly brought up, loved, cared for. If you think about this country and the world, the places that are the most violent and erratic and destructive are the places where there are many more children than grown-ups. So, yes, we ought to be able to choose to be nuns, and men ought to be able to choose to be priests. And women ought to be able to choose to have four children or six children.

Do you see what you are doing as transforming, because you are daring to teach female human beings that they are human beings? And will that change Buddhism?

Palmo: As I said, in Buddhism, as in most religions, since the books were written by males predominantly, and since most of the authority figures are males, undoubtedly there’s a male voice. So what we are trying to do now is allow the feminine voice to also emerge, as you’re doing. And that comes through education and through practice and through the nuns’ sense of their own self-worth, which is the hardest thing. The education and the practice they can get very easily; the sense of their own self-worth is the harder one for them. But it’s happening, and in a very short time. The monks themselves are very keen for the nuns to become educated; they are the teachers, and they encourage the nuns a lot. I don’t want to give the impression we’re doing this in the face of tremendous resistance from the male side, because that’s not true.

But there is resistance toward higher ordination for nuns in the Tibetan tradition. At the moment, they can only take novice ordination. We’ve received surprising resistance from the monks over allowing nuns to receive the full higher ordination, even though this was granted to them by the Buddha himself. There is also resistance to giving the nuns—who have studied maybe twelve, fifteen, twenty years—any official acknowledgment or title. It’s like going to college and, at the end of it, not even getting an M.A. or a Ph.D. You just say, well, I studied. So we have a ways to go, but we’re going.

Steinem: Here, too. Every time I’m at a graduation, I think: What if the guys got a spinster of arts degree instead of a bachelor of arts degree? And a mistress of science? And worked really hard to get a sistership? I love language, so it’s fun to try to change consciousness with language. I think one of the ways we know that we’re on the right track is that laughter is okay. What are some of the signs you look for?

Palmo: I think it’s very important for people to recognize that just as we ourselves wish for a sense of well-being and happiness and don’t want to be made miserable, so does everybody we meet. We’re actually very connected, including animals, in our wish for inner well-being and not to be hurt. What if people just thought about that, you know, just sitting in a theatre or on a subway? What if we were conscious that all the people around us, whatever they might look like, in their heart of hearts, really want to feel okay? What if your first thought for everybody you meet is not judgment but “May you be well and happy”? If we could manage that much, it would change the world, wouldn’t it?

Steinem: Yes, empathy is the most revolutionary emotion, absolutely. I don’t know whether traditions other than Christianity have a golden rule statement like “Do unto others as you would have others do unto you”—probably everybody has that—but I often think that for women, we need to reverse it. We need to treat ourselves as well as we treat other people.

Palmo: Absolutely.

Steinem: Because, as you say, the young women you teach have been so invaded by the idea that they’re not as worthy as male human beings.

Palmo: When the Buddha taught loving-kindness meditation, which is a very important meditation in Buddhism, he said you start by sending lovingkindness to yourself. You wish for yourself to be well and happy, peaceful, and at your ease. When you really feel a warmth and kindness toward yourself, then you send it out to those you love, to those you feel indifferent toward, and to those you have problems with. But you always have to start from where you are, because until we have it inside ourselves, how can we give it out?

Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo, originally from London, was one of the first Westerners to be ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun. She is the subject of the biography Cave in the Snow, which describes her twelve-year retreat in the Himalayas, and is the founder of Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery in Tashi Jong, India, where she currently resides.

Gloria Steinem is a writer and longtime feminist activist. She cofounded Ms. magazine in 1972 and helped found the Women’s Action Alliance and the National Women’s Political Caucus. She is the author of Revolution from Within and is currently working on a new book, Road to the Heart: America As if Everyone Mattered, about her more than thirty years as a feminist organizer.