The ethics of Chan Buddhism begin with the ultimate truth that we are already free. However, this intrinsic freedom is shrouded by relative social conditioning, including views about what is harmful or beneficial. Our task as practitioners is to bridge the ultimate and relative through the practice of ending all harm, cultivating all virtues, and helping all beings. These three pure precepts (Sanskrit: trividhani silani) are inspiring, but what do they entail in the practice of avoiding harm?

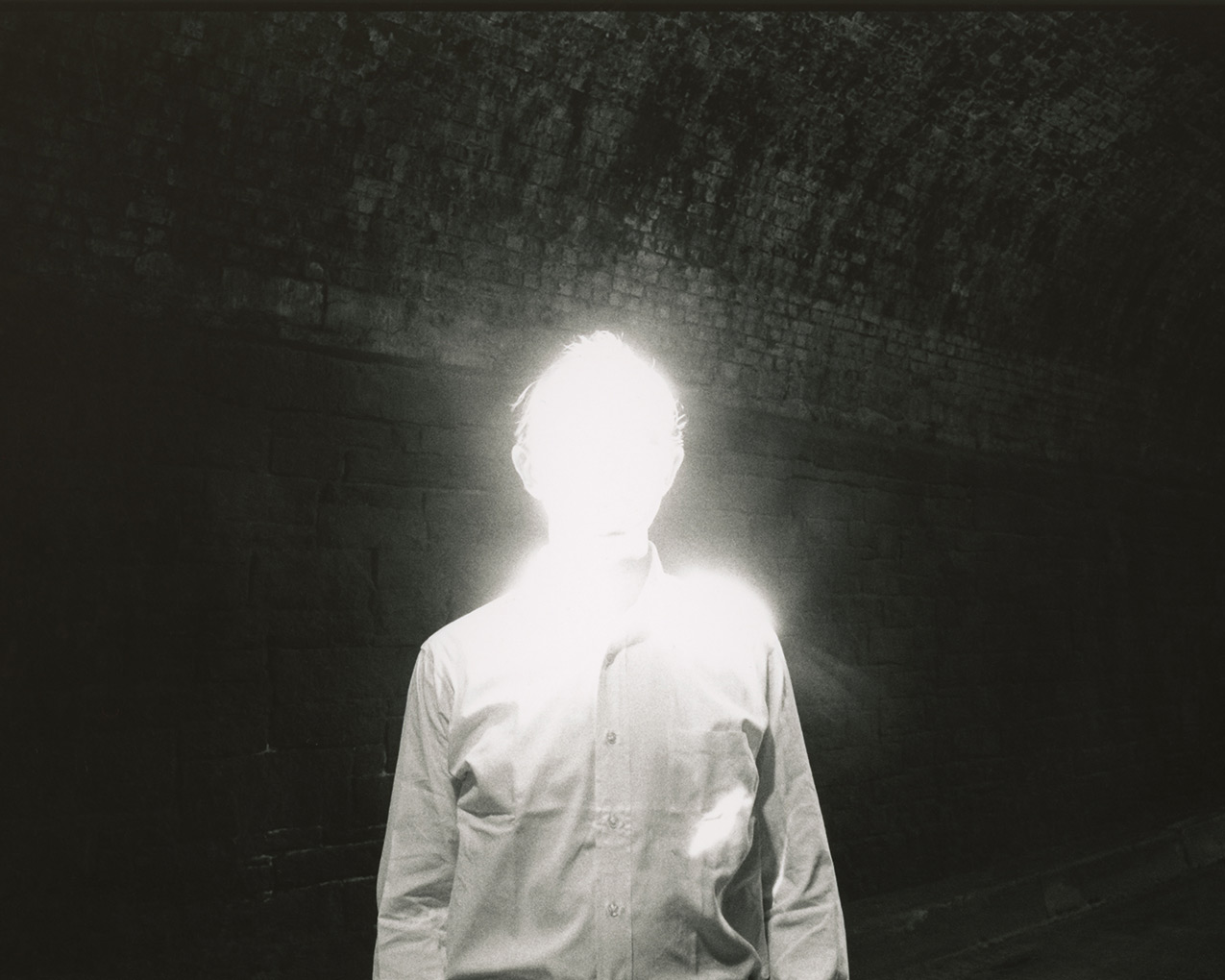

There are three Chan principles on which we can rely to end harm, cultivate virtue, and help all beings. The first is to recognize that all beings, including us, have buddhanature. That is, freedom is our true nature. Buddhanature, or freedom, is just another expression for awakening, selfless wisdom, emptiness, or the truth of no birth and no death. “No birth” means that vexations and harm (Sanskrit: klesa) do not arise; “no death” means that virtues (kusala) do not cease. This is our true nature. While people’s actions may be viewed as harmful or helpful from different changing perspectives and standards, people should not be limited by such containers. Freedom already exists in everyone, and everyone has the potential to recognize it.

The significance behind the first principle is to see the goodness and potential in ourselves and others. This is empowering and healing. We engage in harm because we are lost in self-referential motives; we have lost sight of our true nature. Giving ourselves the space to see our innate freedom from vexations is wisdom. Recognizing the true nature of freedom in others is compassion. This is the way to help all beings.

Why should we let vexations and harm (like greed, hatred, arrogance, envy, and self-centeredness) define us? We don’t need to give in to them. Instead, we practice facing vexations directly: What is their root? There may be reasons and conditions why they arise, but do they really arise? From where do they arise? The mind, the heart, or the body? If we look deep enough, at the core of all vexations is freedom (early suttas such as the Mulaka Sutta and many Mahayana sutras teach this). This is no birth. In freedom there are possibilities. Possibilities for what? For virtues to come through, like generosity, forgiveness, patience, humility, and gratitude. This is no death.

This leads to the second principle: there is a difference between harmful and helpful actions on a conventional level, but that difference is mediated by self. Teachings on harm and benefit are meant to free us. They should not be used to judge others. As the Vimalakirti Sutra says, when our mind is pure, free from self, the world is pure. When we have a pure mind, we see the world the way the Buddha sees the world. To our discriminating minds, harm and benefit seem drastically different; in awakening, they are the miraculous workings of buddhadharma to save all beings. The difference between these two perspectives is the presence or absence of our own self-attachment.

“Giving ourselves the space to see our innate freedom from vexations is wisdom. Recognizing the true nature of freedom in others is compassion. This is the way to help all beings.”

Harm and benefit are context-driven and always changing, determined by causes and conditions and their effects. Most people reify these distinctions based on self-reference—what is harmful to me, what is helpful to me. This “me” may be extended to “us,” but it’s the same selfing that’s happening. From selfing comes the sense of gaining or losing, having or lacking, and good and bad. For example, maybe you feel it’s harmful if your tax rates go up, but perhaps that money is being spent on school meal programs for children from low-income families. Those kids may find it helpful. Seeing the workings of causes and conditions, we ask ourselves: what’s my motive for feeling this way? Whose benefit does it serve? We need to expose that what we deem “harmful” rests on our own sense of me, I, and mine.

Buddhism has lists of what is “helpful” and “beneficial” or skillful and unskillful—these function as guardrails, so we know what to cultivate and what to avoid. However, we cannot be rigid about them, believing them to be absolutes. In Yogacara Buddhism, one of the five erroneous views is rigid attachment to the precepts. (The other four are fixed views about the existence of self; extreme views of eternalism or nihilism; views that deny cause and effect; and holding strong opinions about things.) Rigidity is selfing, which hijacks anything and turns even buddhadharma into harm. Thus, we must use wisdom, beyond our own preferences, to recognize the utility of concepts like harm and benefit.

Consider, for example, the story of Nanda, the Buddha’s half-brother (Mahaprajapati’s own son). Nanda wanted to quit being a monk and go back to lay life where he could indulge in sensual pleasure with an attractive woman. The Buddha, as a skillful means (Sanskrit: upaya), brought him to a heavenly realm to see divine nymphs and promised him five-hundred nymphs if he would remain a monk. Nanda became diligent in practice. The other monks then taunted Nanda for practicing only for the sake of getting nymphs, which gave rise to repentance in him. In his diligence and humility, Nanda ended up becoming an arhat and no longer lusted after any women or nymphs.

The Buddha knew the conditions that would bring him to awakening. The right conditions and context brought about Nanda’s liberation. What appears to be absurd and unhelpful—the Buddha promising Nanda five-hundred nymphs—turns out to be helpful. This story questions our notions of ethics and what might be considered “harm.” Was it harmful for the Buddha to take Nanda to the deva realm to see the nymphs? Was it harmful to encourage and leverage Nanda’s lust? Was it harmful for the other monks to mock him? On one hand, we might think that these actions are harmful. But on the other hand, the action led to Nanda’s awakening and freedom from sensual desire. How should we label such an action?

This story should not be used to support teachers who have claimed to use “skillful means” to take advantage of and harm students. Far from it. The Vimalakirti Sutra clearly states that skillful means are something that only an eighth-bhumi (i.e., highly accomplished) bodhisattva can exercise. The point of the story is to let go of the conceit to judge actions and people. Even what appears to be vexations can lead to awakening. Rather than indulge the impulse to impose rigid ideas of harm and benefit, have the humility to recognize that we don’t know. This leads to the next principle.

The third principle is that we must cultivate humility. It’s easy not to do the most obviously harmful acts. But in most situations, the harm we might do is subtle and unintentional—for example, undermining someone’s confidence or simply failing to be fully present to someone when they’re in pain. A concrete Chan practice of cultivating humility is repentance prostrations. This is an embodied act of giving form to the formless truth of freedom. Cultivating it keeps selfing to the minimum and fosters understanding and kindness toward others. It has nothing to do with guilt. We repent because we acknowledge our harmful actions and impulse for rigid views. In acknowledging them, we free ourselves and others from fixations. Humility allows us to diminish arrogance, recognize the buddhanature in everyone, including ourselves, and realize that every moment is a new beginning. This is how to help all beings.