Introduction by Anne Carolyn Klein

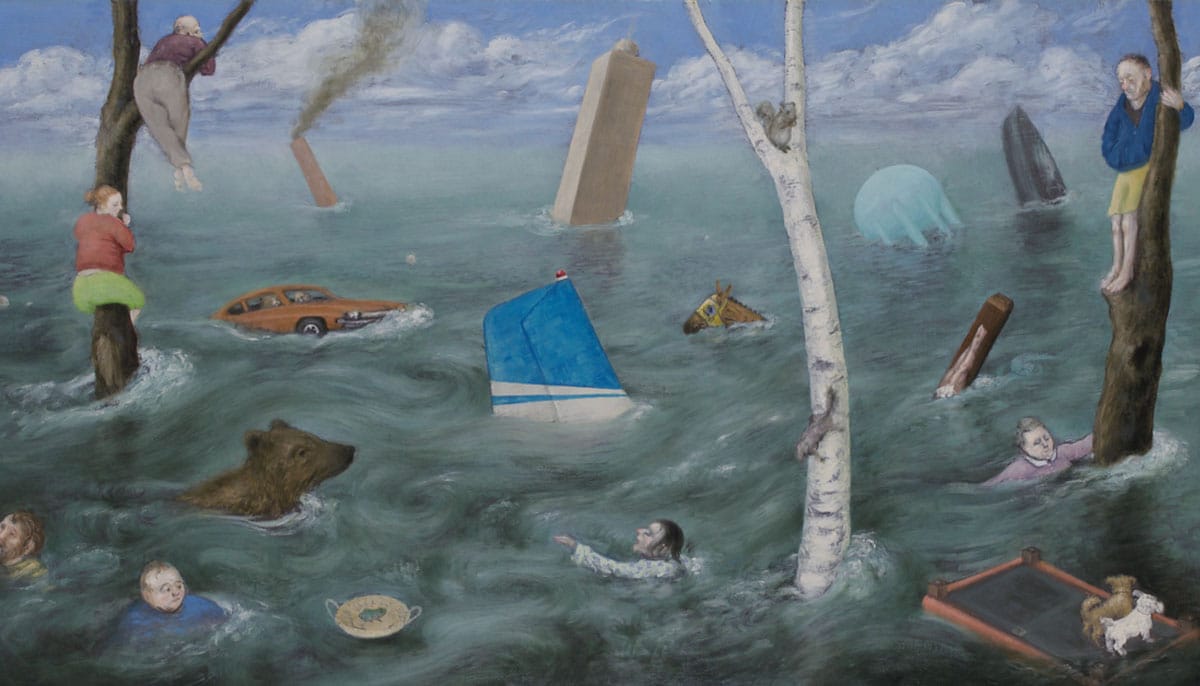

The power and unpredictability of sudden suffering has been dramatically illustrated around the world recently – hurricanes, refugees, mass shootings in the US. It would be a mistake, however, to equate dukkha, a centerpiece of Buddhist teaching, only with such devastating drama. Its scope extends far beyond this to include a much more subtle state of vulnerability that persists even in the absence of manifest pain, even in the midst of apparent contentment.

Buddha’s four ennobling truths present dukkha as the key to the knot in our existence, a knot that unravels only if we look into it closely. Mahayana traditions in Tibet speak of the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths. The four aspects of the first truth, dukkha, evoke the entire horizon of the path: pain, impermanence, emptiness, and selflessness. And indeed, looking closely into the pervasiveness of instability in our lives, we begin to see through the illusion of stable happiness and permanence of any kind; we realize that our personhood is not substantial, that our real selves are not invulnerable to causes and condition

When we recognize it, when dukkha and its core are as apparent to us as a hair on our eyeball, we begin to wake up. We cease to be at odds with, or divided from, our real nature. Not knowing that nature, we feel separate from it. For the eleventh-century Tibetan sage Gampopa, this separation was the hallmark of the “ordinary person” or so sor skyes bu – a term that in fact means someone who is “individuated” or experientially separate from understanding their nature.

Important as it is, dukkha is also not the whole story. In virtually all Buddhist traditions, the narrative of suffering has been balanced to a greater or lesser degree by the narrative of our intrinsic purity, our definite capacity to escape suffering. The limits of dukkha, then, are also crucial to the path. In the Pali canon’s Anguttara nikaya, Buddha explains that while the afflictions that cause suffering may come and go, the mind is always luminous. Mahayana emphasizes that our minds are empty in that we are never utterly stuck in any affliction or untoward habit pattern, no matter how pernicious. Asanga, the Indian master for famous meeting Maitreya in visions and receiving many teachings from him, emphasized that our essence is like stainless space, the dharmadatu, the real nature of buddhas and non-buddhas alike. Longchenpa, the great Nyingma architect of Dzogchen in Tibet, cited Asanga to emphasize the crucial importance of recognizing this relentlessly promising and unassailable aspect of our nature.

This is our other face, what Zen calls your face before your mother was born. If we don’t recognize this face, Asanga says, we won’t appreciate the unsatisfactoriness of ordinary experience – nor will we seek freedom from it. Catching a glimpse of this face early on gives us the strength to look deeply into the well of our own vulnerability. Knowers of reality, said Vasubandhu, have the final, full, undefended recognition of dukkha.

Buddhadharma: Dukkha is the starting point of Buddhist teachings, but not everyone speaks about it in the same way. Speaking from your own tradition, what does dukkha mean?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: In the Pali suttas, the discourses of the Buddha, the word dukkha is used in at least three senses. One, which is probably the original sense of the word dukkha and was used in conventional discourse during the Buddha’s time, is pain, particularly painful bodily feelings. The Buddha also uses the word dukkha for the emotional aspect of human existence. There are a number of synonyms that comprise this aspect of dukkha: soka, which means sorrow; aryadeva, which is lamentation; dolmenasa, which is sadness, grief, or displeasure; and upayasa, which is misery, even despair. The deepest, most comprehensive aspect of dukkha is signified by the term samkara-dukkha, which means the dukkha that is inherent in all conditioned phenomena simply by virtue of the fact that they are conditioned.

Konin Cardenas: In the Zen tradition, dukkha is often translated as “suffering,” although more often it means dissatisfaction or the nagging sense that something is off, or sometimes even existential angst. It seems that dukkha is discussed more explicitly in American Zen than it commonly has been elsewhere in the Zen world. In my experience, Japanese Zen tends to assume that people come to practice seeking enlightenment—I can’t think of a single time I heard the word “dukkha” used during my Japanese training. American Zen, however, acknowledges that whether or not people are seeking some kind of transcendent experience, they often come to practice motivated by the feeling that their life is difficult; I hear “dukkha” often at the places where I’ve trained in the U.S. But regardless of where it’s practiced, Zen identifies the fundamental source of suffering as confusion about the true nature of things.

If we don’t spend time considering what dukkha is, then we won’t seek liberation and awakening. Instead, we’ll use the dharma only to make our samsaric life a little bit better.

-Thubten Chodron

Mark Unno: The suffering of samsara is due to human attachment. In the Jodo Shinshu tradition, we sometimes simply say, “Things don’t go the way I want them to.” It’s a relatable way of talking about attachment as a fundamental cause of suffering. Within that, there is physical suffering such as illness or injury, and there is emotional suffering of various kinds, but those might be categorized as finite sufferings that are addressed within the tradition; the fundamental suffering is the suffering of existence, which is due to attachment to existence, particularly ego attachment.

In Shin Buddhism, the term we use most often to describe the cause of dukkha is “blind passions.” Human beings are driven by their passions. There’s nothing inherently wrong with the basic desires for food, sleep, sex, success. But problems arise when we grow attached to preconceived notions of how to fulfill those desires, to notions of who we think we are or should be, or to who we think others should be or are. It’s really the attachment to notions of reality that causes our feelings and desires to become blinded, hence the term “blind passions.”

Thubten Chodron: I think “suffering” is a very confusing translation for the word dukkha. Suffering often refers to painful feelings and only that, whereas the word dukkha is much more inclusive. We often speak of three types of dukkha. The first is painful sensations, which can be mental or physical. The second is the dukkha of change—even when we have happiness in samsara, it doesn’t last. The activity that we believe is bringing us happiness isn’t truly of the nature of happiness; if we keep doing it, eventually it too becomes painful, like eating too much and eventually feeling sick. The subtlest level of dukkha is the pervasive dukkha of conditioning, taking the five aggregates again and again under the influence of afflictions and polluted karma. Even though we want happiness and peace, because our mind isn’t free from mental afflictions—ignorance, animosity, and attachment—and the karma or actions that we perform under their influence, we are reborn in cyclic existence and experience dukkha again and again.

Buddhadharma: Are there English translations of dukkha that are preferable to “suffering”?

Mark Unno: There can be a lot of confusion around the term, but I like “suffering” as a translation; it’s a relatable term that has deep resonance with the fundamental condition that Buddhism is seeking to address. It’s also the most common translation, and over time, especially in a religious context, words in the vernacular can absorb more subtle layers of meaning. So when “suffering” is used within the Buddhist context now, it’s understood with an increasing degree of sophistication.

Thubten Chodron: My experience is that when people hear “suffering,” they think of the ouch kind of pain, either physical or mental, so when their lives are going well they think, “My life isn’t the nature of dukkha. I have a house, a job, a family—everything is fine. I’m not suffering.” Similarly, when you’re trying to encourage compassion, people can readily have compassion for those who are poor or sick, but they don’t think of extending it to residents of Beverly Hills or the West Side of Manhattan. So I think the word “suffering” actually limits people’s understanding of dukkha. I just use the Sanskrit and Pali term dukkha now and explain it when I talk. Sometimes I translate it as “unsatisfactory circumstances,” but that becomes rather bulky.

Is it the case that all of the misfortune and disappointments that come to us, including physical pain and illness, are necessarily the result of our past karma? In the Buddha’s suttas I have not found a statement to that effect.

-Bhikkhu Bodhi

Konin Cardenas: I agree. Using a phrase like “the unsatisfactory nature of things” or simply using the term dukkha and explaining it is preferable because it encompasses the pervasive way in which dukkha is a part of life—that it’s more intrinsic than a tension between positive or negative or joyful versus not joyful.

Bhikkhu Bodhi: It’s good to have a little debate here. I’m more comfortable with dukkha, though I’m also going to come to the defense of Mark’s preference for “suffering.” I agree that dukkha has a much more extensive meaning than the English word suffering; without explanation, it could easily be misunderstood. However, the Buddha picked up the word dukkha—which during his time meant suffering—and placed it within the architecture of his teaching, from which multiple ramifications of the word arose. Similarly, through explanation one can show that what we call suffering encompasses a much wider range than we commonly understand—we start with the word that indicates pain, dissatisfaction, what is defective or inadequate, and then show that the things that we take to be pleasant, blissful, and enjoyable, when examined more closely and deeply, are in fact unsatisfactory and inherently defective.

There are a number of discourses in which the Buddha explains how when a meditator attains the higher levels of meditative absorption, the advanced stages of samadhi—the four janas, the four divine abodes, the bramaviharas, and the four formless meditations—and then examines those states that we generally consider to be sublime or blissful, they too will be seen as impermanent, as dukkha, as a disease, a boil, an affliction, a tumor, and so forth. So we can extend our understanding of suffering to include even these exalted states.

Buddhadharma: Rather than insist on a single translation, might it be better to talk of dukkha as a spectrum of experience?

Thubten Chodron: Yes. One end of the spectrum is mental and physical suffering. The other end is the basic fact that our minds are not free. Due to afflictions and karma—the second noble truth, the truth of the origin of dukkha—continuous rebirth in samsara occurs. That’s a very subtle kind of dukkha that is difficult for people to realize; we don’t even tend to think of it as anything undesirable. We just take our body and mind for granted. But it is said that aryas, those who perceive reality directly, perceive that kind of dukkha with the same intensity as we would having a hair in our eye; they desire to be free from that unbearable experience. If I don’t continually anchor my practice in awareness of that kind of dukkha, my practice isn’t touching the essence of what the Buddha was trying to get across. It limits practice to overcoming the unhappiness, confusion, and pain in this life, whereas dukkha really embraces the whole experience of uncontrollable rebirth. I think that’s important for us to understand.

Mark Unno: A practical way to think about that spectrum in the Shin tradition is that oftentimes one can take the more superficial level of suffering, with mental or physical pain, as a point of entry that leads the practitioner into a deeper awareness of the fundamental condition. The parallel to that in terms of karma is the relationship between individual and collective karma. As one’s practice deepens, one becomes increasingly aware that collective karma is actually not separate from one’s own individual karma, that all karmic suffering is realized as one’s own suffering.

Konin Cardenas: I agree that presenting dukkha as a spectrum is important. It helps the practitioner understand that even in the midst of a life that’s seemingly comfortable, there is still dukkha that can be addressed by our practice. There is another kind of liberation that isn’t about becoming more comfortable materially or psychologically.

Bhikkhu Bodhi: If we don’t accept that deeper dimension, then when dukkha gets adapted to the Western mentality, we wind up with what I would call a psychologicalization of the Buddha’s teaching. That is, dukkha becomes explained almost entirely as psychological or emotional suffering—distress, dissatisfaction, worry, anxiety, fear, concern, and so on. When it is explained in that way, one sees the aim of practice as overcoming those states of psychological uneasiness in order to live peacefully and happily in this present life. That seems to be the drift of what I would call the secularized mindfulness movement that has grown out from Buddhism. It presents a partial explanation of dukkha according to the Buddha’s teachings; if we take that to be a fully adequate explanation, then we are impoverishing the teaching and turning it into a kind of therapeutic discipline rather than a liberative one.

Buddhadharma: Even when we talk about categories of dukkha that include physical pain, we still tend to talk about dukkha as an experience of the mind, such as a response to that pain. In light of concrete suffering—illness, poverty, the tragedies of war—how do we clarify that dukkha isn’t just in our heads?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: This is something that has come to concern me very much over the last decade or so. The social dimension of dukkha as real, concrete suffering is an aspect that we tend to overlook. In these manifestations of suffering, we can see the relationship between the first and second noble truths expanded into a collective dimension. Take what happened in Houston—we can see how the ravages of climate change pouring down on that city fundamentally stem from the deep defilements of the human mind, from the greed of fossil fuel corporations that have long denied the relationship between carbon emissions and climate change, to the politicians who have been blocking attempts to address climate change, to the media who have largely failed to highlight the connections between torrential floods, wildfires, and climate change. We could apply the same analysis to understanding the wars going on in Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Somalia.

For me, the most challenging form of dukkha is generational dukkha, the suffering that gets passed on from generation to generation: violence, abuse, or unskillful acts. It’s pervasive.

-Konin Cardenas

Mark Unno: Shin Buddhism, and more broadly Mahayana Buddhism, includes attention to both outward material suffering and internal mental suffering. Buddhism in the West needs more discussion about the relationship between these two. We need to address social ills and social and environmental engagement. And I think Mahayana Buddhism has plenty of discourse that makes room for that and encourages that. But no matter what we do to address social and environmental concerns, without sufficient focus on the fundamental suffering of samsara, we will not get at the root cause; in fact, we may end up causing even greater suffering.

Konin Cardenas: Our practice is very much an embodied practice. I can’t think of a single Buddhist tradition in which that’s not true. The arising of the bodhisattva vow comes from the fact that even a cursory examination of your own body and mind and the world around you leads you to see that beings are suffering, that they are dissatisfied with their state. They’re suffering as a result of being in bodies; they’re suffering as a result of being in a world in which compassion doesn’t show up for them in a very real way. I don’t think there’s a question about whether dukkha is mental or physical. Certainly in Zen we understand those two to be completely intertwined. The bodhisattva says, “Yes, of course! Suffering in my own body and mind is a tiny grain of sand in the entire universe of suffering bodies and minds.”

Thubten Chodron: I would agree with Konin that the very real experience of physical suffering is universal to all embodied beings. Physical suffering is in fact the entryway into seeing the dissatisfactory nature of life in samsara. But when we move into the bodhisattva’s way of seeing, we train our mind to see others’ dukkha—any of the three kinds of dukkha—as if it were our own, to the degree that as much as we find our own dukkha unbearable, we find other beings’ dukkha unbearable.

My concern with Buddhism in the West is that there’s some block to really looking deeply at what dukkha means. People want light and love and bliss. Many people come to Buddhism to achieve a better psychological state and feel better about themselves, and that’s fine—we can help them on that level. But that’s not the depth to which the Buddha’s teachings go. If we don’t spend time considering what dukkha is, then we won’t seek liberation and awakening. Instead, we’ll use the dharma only to make our samsaric life a little bit better. That’s one of my fears for Buddhism in the West, that we lose the liberating aspect of the dharma.

Buddhadharma: So how can we work most effectively with dukkha?

Konin Cardenas: In Zen, there’s a strong emphasis on our ability to directly encounter whatever states of body and mind present themselves, to learn how to find our groundedness within what arises, relinquishing both aversion and attraction. So one way of beginning to address dukkha is simply learning the stability of mind, the ability to be present with mind and body. Once practitioners are able to do that, then they begin to explore how it is that the activity within their lives is actually driving the arising and falling away of these very states of body and mind. That’s when we begin to understand the teachings about “your face before your parents were born” or “dropping off body and mind,” teachings that point at something more fundamental than the psychological study of the self; we begin to see the self as interdependent arising. That self is in harmony with the state of things as they are; when the state of conditions is like this, they must be that way.

Mark Unno: Shin Buddhism places a great emphasis on how the awareness of suffering—and therefore also the awareness of great compassion, mahakaruna—arises within the individual mind. Great compassion, which is an expression of the dharmakaya, of the cosmic buddha body or the highest truth of emptiness, embraces and ultimately dissolves suffering. It can arise within the individual but does not come from the individual. For that reason, we call it “other power,” as it does not derive from the ego but rather is unconditioned.

Bhikkhu Bodhi: The general prescription the Buddha offered to the problem of dukkha through the four noble truths is the noble eightfold path, within which we find specific methods for working with different aspects of dukkha. For example, when we experience the dukkha of bodily feeling, the most appropriate way to deal with it is to observe the bodily feelings from the position of nonidentification. Instead of taking the feelings to be mine, thereby intensifying them and then seeking escape from them by indulging in sensual pleasures, one can focus attention on the feelings and just watch them as momentary states that arise, stand for a brief moment, and then pass away. In this way, even though the painful feeling might continue, it will not trigger emotional distress, at least not to the same degree. A similar method can be applied to emotional types of suffering. One could not only observe the states of distress, worry, and fear, again from a position of nonidentification, but also probe more deeply into their origins. Careful observation reveals they are all arising from some kind of grasping, such as grasping the desire to achieve a particular result and then fearing that circumstances will frustrate one’s expectations.

On a deeper level, one sees that all of these states of emotional distress arise from grasping for the inherent existence of a self. Finally, to overcome the deepest dimension of dukkha—what we call “the dukkha that pervades all conditioned phenomena”—one has to develop insight into the three marks of existence: impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and selflessness, to the point where one achieves the world-transcending paths that finally and completely eradicate the defilements that keep one in bondage to the cycle of birth and death.

Thubten Chodron: One technique in our tradition for working with the first layer of dukkha, the painful physical and mental feelings, is to understand that these are a result of our negative actions in a previous life, or even in this life. So rather than react with anger, blame, denial, and frustration, we see unpleasant experiences as a result of our own actions. There’s nothing to blame outside of myself, and if I don’t like experiencing these results, I need to abandon activities that are harmful and take up activities that are more beneficial for self and others. Another technique that we use is generating great compassion in response to dukkha. With respect to our own dukkha, we generate the determination to be free of samsara, which propels us to realize the nature of reality and free our minds from the uncontrolled cycle of rebirth. Then we turn that same feeling of wanting to be free from samsara and its causes to other living beings; we generate great compassion and the thought “I want to become a fully awakened buddha in order to benefit all these beings most effectively.”

Another practice to use with any of the three kinds of dukkha is called the “taking and giving” practice, in which we imagine taking on the dukkha of other living beings with compassion, using it to destroy our own self-centeredness and self-grasping ignorance, then wishing happiness and the causes of happiness on others, imagining giving our body, possessions, our merit, everything to other living beings to alleviate their dukkha and to bring them joy. This is a profound method. I’ve done it sometimes when I’ve personally been experiencing a lot of pain, and it transforms the mind.

As one’s practice deepens, one becomes increasingly aware that collective karma is actually not separate from one’s own individual karma, that all karmic suffering is realized as one’s own suffering.

-Mark Unno

We can also bring mindfulness that is conjoined with wisdom to understand dukkha, observing our impermanent nature and then going beyond that to see that we’re grasping dukkha as inherently existent, that the causes for us experiencing dukkha—the ignorance, anger, and attachment—are underlain by grasping at inherent existence. So we can use the meditation on emptiness, on selflessness, to change how dukkha appears to our mind and also to stop creating the karma that leads to at least the first two kinds of dukkha.

Buddhadharma: The idea that dukkha is the result of our karma is hard to hear. It sounds like blame.

Thubten Chodron: It is hard to hear—it entails accepting responsibility for our actions, and we tend to blame our misery on things outside of ourselves that we often cannot control. But saying that this misery is a result of our own karma is not blaming ourselves. It’s not saying that somebody deserves to suffer. Do not put a Christian overlay of karma suggesting reward and punishment on the Buddhist notion of karma. It’s just that when you plant daisy seeds, you get daisies, and when you plant chili seeds, you get chilies. The point is to look at our actions and understand that they influence our experiences. At the level of societal suffering, it’s very clear that human actions are producing poverty, climate change, and war. We have to accept responsibility for our actions, but that does not mean we blame ourselves. Blame and responsibility are two completely different things.

Mark Unno: Yes, there is a great difference between taking responsibility and self-blame. In my tradition, we place emphasis on applying the teaching of karma to ourselves, not other people. Our founding teacher, Shinran, said, “When I reflect deeply on the teaching of karma and the working of great compassion, I realize it is for myself alone.” It’s not the case that we can’t talk about others’ karma, but when we do, it tends to shift over to blame unless we place ourselves at the center of karmic responsibility. For example, if a mother says to her child, “You need to take responsibility for cleaning your own room,” that guidance won’t carry much weight unless the mother keeps her own room clean. And the mother can convey this guidance to her child with a sense of caring for the sake of the child’s maturation, of coming into her or his own.

The issue is not in the words per se but in how we express ourselves in terms of karmic responsibility. Am I willing to be the focal point for karmic responsibility?

Bhikkhu Bodhi: Is it the case that all of the misfortune and disappointments that come to us, including physical pain and illness, are necessarily the result of our past karma? In the Buddha’s suttas I have not found a statement to that effect. That idea has come into the Buddhist tradition, but it doesn’t seem to stem from the Buddha’s discourses as they’ve been preserved, at least in the Pali tradition. One method the Buddha teaches to deal with this question of karma, and that I use, is to recognize that the principle of karma and its fruit applies to one’s actions in the present. So if one engages in unwholesome actions in the present, then those actions, if they get the opportunity to mature, will eventually bring painful, disagreeable results in the future. But this does not necessarily mean that all of the painful, disagreeable experiences we undergo are the reflections of our past karma. Probably a large proportion of them are, but it’s not necessarily the case that all of them are.

Buddhadharma: From the perspective of your tradition, what is the ultimate goal when working with dukkha? Is it to eradicate it? To make friends with it? What are we aiming for?

Konin Cardenas: In the Zen tradition, the view is that each moment is a resolution of all the causes and conditions that led up to it. All of the conditions and causes are harmonious; they’re done. That includes karma. So the ultimate relationship to dukkha would be to see that the causes and conditions necessary for the suffering or dissatisfaction that’s present are complete, and our response to the moment now is what determines whether they will arise again or whether they will cease. Our ability to step into this larger understanding of self—not as fixed but as the interdependent arising of all things—allows us to actually see the causes of suffering and the causes of the end of suffering, and to be able to arrive at some kind of acceptance, not in the sense that everything is okay but in the sense of acknowledging what is with respect to dukkha in our lives and the things we do to contribute to it.

Mark Unno: In the Mahayana tradition, we say that if we truly deepen our awareness of samsara, we come into the awareness of nirvana. We realize that the very thing we perceive as the realm of suffering or discontent becomes transformed into our awareness of nirvana or emptiness. So we emphasize that we don’t try to get rid of suffering; instead, we deepen our awareness of dukkha, and in that deepening awareness we realize that the true nature of the unfolding of reality is great compassion. Suffering becomes transformed into great compassion, yet it doesn’t get transformed into something that is different from its very nature. The very nature of suffering reveals itself to be great compassion.

Bhikkhu Bodhi: The goal of the Buddha’s teaching in the early discourses, as we can see from the formula for the four noble truths, is in fact the cessation of dukkha. The Buddha says, “What I teach is just dukkha and the cessation of dukkha.” In the early discourses, we distinguish two aspects of the cessation of dukkha with two dimensions of nibbana. One is the dimension of nibbana to be realized in this present life, also called the nibbana with residue remaining. This is the state that’s attained when all of the defilements have been eradicated. It’s explained as the destruction of greed, hatred, and delusion, but still this residue of dukkha remains throughout the body with its sense faculties and mental processes. Even the arhat—who has eradicated all of the defilements right down to their roots, who lives in peace, harmony, tranquility, and happiness, no longer experiencing any dukkha as grief, sorrow, worry, or anxiety—still recognizes that the experience through body and mind is inherently unsatisfactory, that it contains a residue of dukkha. The final goal of the teaching, then, is the cessation of the continued process of rebirth. That occurs when the liberated one passes away; what remains is called the nibbana element without residue remaining. In that state, there is no longer any continuation of the five aggregates, the conglomeration of physical and mental processes that constitute experience. That, according to the Buddha, is the ultimate cessation of dukkha.

Thubten Chodron: Yes, according to our tradition also, the goal is to cease dukkha completely for ourselves through the realization of the emptiness of inherent existence and also to be able to help others do the same. Of course they have to do the work themselves, but if we can become skillful teachers by attaining buddhahood, then we can help them understand the causes of their dukkha and the path to eliminate it.

I don’t really understand what you mean about “making friends with dukkha.” But I would say that accepting our dukkha when we’re in the middle of painful experiences—rather than blaming others and getting angry—lessens the suffering. We can accept the present dukkha and still know that we can be free of dukkha in the future. To do this, we practice abandoning the causes for misery and creating the causes for joy and fulfillment.

Buddhadharma: What has been the most challenging or difficult aspect for you in working with dukkha?

Konin Cardenas: For me, the most challenging form of dukkha is generational dukkha. By that, I mean the suffering that gets passed on from generation to generation: generational violence, abuse, or unskillful acts. Much of my early practice was focused on finding ways the dharma could help me shed the generational dukkha that I have been exposed to, so when I see it in the world, when I see the passing on of violence across generations and in social settings, it’s very painful to watch. And it’s pervasive. I try to address that in my teachings. When I encounter people experiencing that form of dukkha, it’s something I feel needs to be met very directly with compassion, clarity, and insight.

Mark Unno: Early on in my practice, it was a great challenge to deepen my samadhi practice, samadhi in this case denoting the depth of meditation that embodies both wisdom and compassion. In Shin Buddhism, we recognize how limited we are as foolish beings and simultaneously receive the illumination and samadhi of Amida Buddha. As a teacher, the most important quality I bring to students is to serve as the living example of a foolish being, constantly reminded to return to beginner’s mind while also serving as the conduit and embodiment of the inconceivable depth of the samadhi of infinite light, of Amida Buddha, or of buddhanature. Without the spontaneous power of this inconceivable samadhi, it is extremely difficult to walk the Buddha way with others who carry that burden of intergenerational karma, which is pretty much everyone.

Thubten Chodron: One of the challenges I face is slipping into blaming others for my dukkha instead of accepting responsibility. Another problem I have is not really seeing the depths of dukkha, especially the pervasive dukkha of conditioning. It’s easy to try to just tweak my samsara, to adjust my life to make it a little bit more comfortable without really wanting to be free from all of samsara. Also, it’s sad to look at the world and see how we create so much unnecessary suffering for ourselves. Everybody wants happiness and doesn’t want suffering, and yet again and again as individuals, as groups, as countries, we keep creating causes for suffering, creating conditions that torment others and ourselves. That’s painful to see, but it also energizes my practice of compassion.

Bhikkhu Bodhi: For the past forty years, I’ve had a chronic head pain condition that is often disabling and very discouraging. Sometimes, when the pain is very intense, I can barely get out of bed. So it’s been a challenge trying to be productive and functional while enduring this condition, and it’s also been a big obstacle for my meditation. But it’s also been the primary theme of my meditation practice and has helped strengthen it.

I faced a different challenge when I was living in Sri Lanka. I was there at a time when the country had been engulfed by two wars, and even though the central part of Sri Lanka where I was living was safe, I was constantly reading reports about the atrocities taking place on both sides. After I came back to the United States, I had access to the internet for the first time and was able to read about the vast suffering taking place worldwide from natural disasters and from unjust economic, social, and military policies. For me, this awareness has been galvanizing in my relationship to dukkha.

Mark Unno: The topic of dukkha is very timely in this particular moment, which is extremely difficult for so many people. Awareness of suffering is such a cornerstone of Buddhist practice; this awareness is what enables the doors of liberation to open to us. So as profound as the suffering and difficulty we face may be, it is also a moment of great spiritual opportunity.