Gotama Buddha’s familiar story follows the archetypal hero’s journey: he left behind wife and child and renounced the ordinary world to seek the holy life. Dipa Ma followed a similar path, but with an unexpected turn. Ultimately she took her practice home again, living out her enlightenment in a simple city apartment with her daughter. Her responsibilities as a parent were clarified by her spiritual practice; she made decisions based not on guilt and obligation but on the wisdom and compassion that arose from meditation. Instead of withdrawing to a cave or a forest hermitage, Dipa Ma stayed home and taught from her bedroom—appropriately enough, a room with no door.

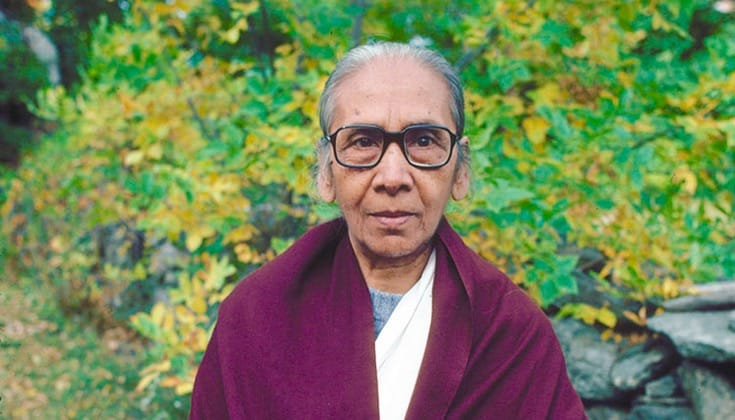

Nani Bala Barua, later known as Dipa Ma, was born in 1911 in a village on the plains of Chittagong in what is now Bangladesh. The indigenous Buddhist culture there traces its lineage in an unbroken line back to the Buddha. By the time Dipa Ma was born, meditation practice had almost disappeared among her clan, but they continued to observe Buddhist rituals and customs.

Though intensely interested in Buddhism from a young age, like most Asian women of her era Dipa Ma had little opportunity to undertake serious spiritual training. However, by midlife she came to devote herself fully to meditation, attaining profound levels of insight in only a short time. She found a way to incorporate her family into her spiritual journey and went on to teach specific techniques for practicing mindfulness in the midst of everyday activities.

Dipa Ma’s influence has been widely felt in the West, in part due to her relationship with the three founders of the Insight Meditation Society. She was a primary teacher of Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzberg, as well as one of Jack Kornfield’s teachers. Kornfield recalls that Dipa Ma’s first questions were always, “How are you feeling? How is your health? Are you eating well?” No matter who showed up or what state they were in, Dipa Ma reached out to them with love. Both Salzberg and Goldstein call her “the most loving person I have ever met.”

IMS teacher Michele McDonald-Smith considers meeting Dipa Ma a turning point in her life. “At the time I met her,” McDonald-Smith says, “there were mostly male role models—male teachers, male buddhas. To meet a woman householder who lived with her daughter and grandson—and who was that enlightened—it was more profound than I can put into words. She embodied what I deeply wanted to be like. For me as a woman householder, I immediately felt, ‘If she can do this, I can do this, too.’”

For lay people who are committed to dharma practice but unlikely to leave home, work and family to live in a temple or monastery, Dipa Ma is a vivid example of what is possible. Even the name she went by suggests her identity as an enlightened householder. After giving birth in middle age to a much-longed-for child, a daughter named Dipa, Nani Bala Barua got the nickname “Dipa Ma,” meaning “mother of Dipa.” The word dipa means “light or lamp of the dharma,” thus the name “mother of light” united the two salient features of her life—dharma and motherhood.

Dipa Ma’s early life followed the expected path of a village girl in East Bengal. At age twelve, she married Rajani Ranjan Barua, an engineer twice her age, who left one week after their wedding to take a job in Burma. After two lonely years in her in-laws’ home, she was sent to Rangoon to join her husband. To the couple’s great disappointment, the young Dipa Ma was unable to become pregnant and to add to this difficulty, her mother died while she was still adjusting to her new life. Although she was eventually able to bear children, she lost two as infants and then fell seriously ill herself. Through it all, Rajani was patient, loving, and wise. The couple adopted her much younger brother, Bijoy, and Rajani suggested to his grieving wife that she treat every person she met as her own child.

“Human beings will never solve all their problems. The only way is to bring mindfulness to whatever you are suffering.”

-Dipa Ma

Dipa Ma raised her younger brother, gave birth to Dipa, and looked after her husband. However, in her mid-forties, after Bijoy had grown up and left home, Rajani died suddenly, leaving Dipa Ma devastated. For several years she was confined to her bed with heart disease and hypertension, scarcely able to care for herself and her young daughter, and she believed she would soon die if she did not find a way to free herself from her burden of grief. She resolved to learn meditation, convinced it was the only way she could save herself. Soon after, she dreamed of the Buddha softly chanting these verses from the Dhammapada:

Piyato jayati soko,

piyato jayati bhayam

piyato vippamuttassa,

natthi soko kuto bhayam.Clinging to what is dear brings sorrow.

Clinging to what is dear brings fear.

To one who is entirely free from endearment

There is no sorrow or fear.

Awakening from the dream, Dipa Ma felt a calm determination to devote herself fully to meditation practice. She turned over everything she had been left by her husband to a neighbor, whom she asked to care for her daughter, and arranged to go to the Kamayut Meditation Center in Rangoon, intending to spend the rest of her life there.

Early in the morning during her first day at the center, Dipa Ma was given a room and basic instructions and told to report to the meditation hall late that afternoon. As she sat in meditation through the day, her concentration rapidly deepened. Later, on her way to the meditation hall, she suddenly found herself unable to move. For several minutes, she couldn’t even lift a foot, which puzzled her. Finally she realized that a dog had clamped its teeth around her leg and wouldn’t let go. Amazingly, her concentration had become so deep even in those first few hours of practice that she had felt no pain. Eventually, the dog was pulled away by some monks. Dipa Ma went to a hospital for rabies injections and then returned home to recuperate.

Once home, her distraught daughter would not allow her to leave again. With her characteristic practicality and resourcefulness, Dipa Ma recognized that her spiritual journey would have to take a different form. Using the instructions given at her short retreat, she patiently meditated at home, committing herself to the diligent practice of awareness, moment by moment.

After several years, Munindra, a family friend who lived nearby, encouraged Dipa Ma, then fifty-three years old, to come to the meditation center where he was studying under the renowned teacher Mahasi Sayadaw. By her third day there, Dipa Ma entered into much deeper concentration. Her need for sleep vanished, along with her desire to eat. In the following days, she passed through the classic phases of the “progress of insight,” which precede enlightenment. On reaching the first stage, her blood pressure returned to normal, her heart palpitations decreased dramatically, and the weakness that had made her unable to climb stairs was replaced with a healthy vigor. Finally, as the Buddha had predicted in her dream, the grief she had carried for so long vanished.

For the rest of the year, Dipa Ma went back and forth between home and the meditation center, where she rapidly progressed through further stages of enlightenment. (As described in the Visuddhimagga, the Theravada tradition recognizes four such stages, each producing distinct, recognizable changes in the mind.) People who knew her were fascinated by her change from a sickly, grief-stricken woman to a calm, strong, healthy, radiant being.

Inspired by this transformation, Dipa Ma’s friends and family including her daughter, joined her at the meditation center. One of the first to arrive was Dipa Ma’s sister, Hema. Although Hema had eight children, with five still living at home, she managed to make time to practice with her sister for almost a year. During school breaks, the two middle-aged mothers would have as many as six children between them. They lived together as a family, but followed strict retreat discipline, practicing silence, no eye contact, and no eating after noon.

In 1967, the Burmese government ordered all foreign nationals to leave the country. The monks assured Dipa Ma that she could get special permission to stay, an unprecedented honor for a woman and single mother, someone with essentially no standing in society. However, though she wanted to stay in Rangoon, Dipa Ma decided to go to Calcutta, where her daughter would have better social and educational opportunities.

“If you are busy, then busyness is the meditation. And when you do calculations, know that you are doing calculations. Meditation is always possible, at any time. If you are rushing to the office, then you should be mindful of rushing.”

-Dipa Ma

Their new living conditions were modest, even by Calcutta standards. They lived in a small room above a metal-grinding shop in the center of the city. They had no running water, their stove was a charcoal burner on the floor, and they shared a toilet with another family. Dipa Ma slept on a thin straw mat.

Soon word spread in Calcutta that an accomplished meditation teacher had come from Burma. Women trying to fit spiritual training in between the endless demands of managing their households appeared at Dipa Ma’s apartment during the day, seeking instruction. She obliged by offering individualized teaching tailored to full lives—but with no concessions to busyness.

Dipa Ma’s long career of guiding householders had already begun in Burma. One of her first students, Malati, was a widow and a single mother who was caring for six young children. Dipa Ma devised practices Malati could do without leaving her children, such as bringing complete presence of mind to the sensation of her infant nursing at her breast. Just as Dipa Ma had hoped, by practicing mindfulness when she nursed her baby Malati attained the first stage of enlightenment.

In Calcutta, Dipa Ma addressed similar situations again and again. Sudipti was struggling to run a business while caring for a mentally ill son and an invalid mother. Dipa Ma instructed her in vipassana practice, but Sudipti insisted that she couldn’t find time for meditation because she had so many family and business responsibilities. Dipa Ma told Sudipti that when she found herself thinking about family or business, she could simply think about them mindfully. “Human beings will never solve all their problems,” she taught. “The only way is to bring mindfulness to whatever you are suffering. And if you can manage only five minutes of meditation a day, you should do that.”

At their first meeting, Dipa Ma asked Sudipti if she could meditate right then and there for five minutes. “So I sat with her for five minutes,” Sudipti recalls. “Then she gave me instructions in meditation anyway, even though I said I had no time. Somehow I found five minutes a day, and I followed her instructions. And from this five minutes, I became so inspired. I was able to find longer and longer times to meditate, and soon I was meditating many hours a day, into the night, sometimes all night, after my work was done. I found energy and time I didn’t know I had.”

Another Indian student, Dipak, remembers Dipa Ma teasing him: “Oh, you are coming from the office; your mind must be very busy.” But then she would fiercely command him to change his mind. “I told her that working in a bank there was a lot of calculating, and that my mind was always restless,” said Dipak. “It was impossible to practice; I was too busy.” Dipa Ma was firm, however, insisting that, “If you are busy, then busyness is the meditation. And when you do calculations, know that you are doing calculations. Meditation is always possible, at any time. If you are rushing to the office, then you should be mindful of rushing.”

Householder practice under Dipa Ma could be as demanding as monastic life. Loving but tough, Dipa Ma asked that students follow the five precepts and sleep only four hours a night, as she did. Students meditated several hours a day, reported to her several times a week, and at her instigation undertook self-guided retreats. Joseph Goldstein recalls how the last time he saw Dipa Ma, she told him he should sit for two days—meaning not a two-day retreat but one sitting for two days straight. “I started to laugh, because it seemed so beyond my capacity. But she looked at me with deep compassion, and she just said, ‘Don’t be lazy!’”

Dipa Ma’s path wasn’t attached to a particular place, teacher, lifestyle, or the monastic model. The world was her monastery; mothering and teaching were her practice. She embraced family and meditation as one, in a heart that steadfastly refused to make divisions in life. “She told me, ‘Being a wife, being a mother—these were my first teachers,’” recalls Sharon Kreider, a mother who studied with Dipa Ma. “She taught me that whatever we do, whether one is a teacher, a wife, a mother—they are all noble. They are all equal.”

Dipa Ma became not only the “patron saint of householders,” as one student called her, but also the embodiment of being the practice rather than doing the practice. For Dipa Ma there was simply the practice of being present, being fully awake, all the time, in every situation; she was a living demonstration that the real nature of mind is presence. Joseph Goldstein said that with Dipa Ma there was no sense of someone trying to be mindful; there was just mindfulness doing itself.

“Her mind didn’t make distinctions,” says meditation teacher Jacqueline Mandell. “Meditation, mothering, and practice all flowed into each other in an effortless way. They were all the same. They were one whole. There were no special places to practice, no special circumstances, no special anything. Everything was dhamma.” She urged her students to make every moment count and emphasized bringing mindfulness to cooking, ironing, talking, or any other daily activity. She often said that the whole path of mindfulness is simply awareness of whatever you are doing. “Always know what you are doing,” she would say. “You cannot separate meditation from life.”

While some teachers make the greatest impact through their words, with Dipa Ma it was, Mandell says, “her natural agile attention: shifting from teaching meditation to parenting to grandparenting to serving tea. A simple presence: all seemed quite ordinary within her completely natural way.” Though Dipa Ma was generous with her instruction, she was often silent or spoke only a few simple words; her students found refuge in her silence and in the unshakeable peace that surrounded her.

By the time she died in 1989, Dipa Ma had several hundred Calcuttan students and a large group of Western followers. A continual stream of visitors came to her apartment from early morning until late at night. She never refused anyone. When her daughter urged her to take more time for herself, Dipa Ma would reply, “They are hungry for the dhamma, so let them come.”

Dipa Ma is remembered not only for her seamless mindfulness and her direct instruction, but also for transmitting dharma through blessings. From the moment she arose each morning she blessed everything she came in contact with, including animals and even inanimate objects. She blessed every person she met from head to toe, blowing on them and chanting and stroking their hair. Her students remember being bathed in love, a feeling so strong and deep they didn’t ever want it to end. To this day, one of Dipa Ma’s students, Sandip Mutsuddi, carries her picture in his shirt pocket over his heart. Several times a day, he pulls the picture out to help him remember her lessons and to offer his respect. He has been doing this every day since her death.

Lay practitioners often feel torn between spiritual practice and the requirements of family, work, and social life. We know that our recurrent dilemmas cannot be resolved by separating parts of our lives and weighing one against the other, yet we become easily lost in that moment of dilemma. Perhaps the image of Dipa Ma can reside in our hearts as a reminder that we do not have to choose. Each dilemma can be accepted as a gift, challenging us to find, again and again and yet again, the middle way in which nothing is outside of our compassion. And perhaps the very process of opening to such challenges will produce a form of family practice that reflects how the dharma can be lived in our particular time and place.