Happiness is a challenging word since it carries so many varied meanings and connotations, and its usage within Buddhist writings is consequently varied and subtle. Hedonic happiness, for example, is a feeling based on pleasure seeking. While Buddhism sees nothing wrong with pleasure, per se, the four noble truths clearly state that the expectation that pleasure will bring lasting happiness is illusory. Any conditional form of happiness is impermanent.

Forms of Happiness in Buddhist Teachings

According to many Buddhist teachers, certain forms of what is generally termed happiness—such as contentment with what one has based on renunciation; an overall sense of well-being that is not based on external circumstances; or eudaimonic happiness (a form of happiness considered the opposite of hedonic happiness and based on behaving virtuously)—are considered helpful in the context of meditation practice, promoting a more relaxed care-free frame of mind that is not centered on striving to get something else or be somewhere else. For example, Chogyam Trungpa says that once we have been inspired by the precision of meditation, “we find that there is room, which gives us the possibility of total naivete, in the positive sense. The Tibetan for naivete is pakyang, which means ‘carefree’ or ‘let loose.’”

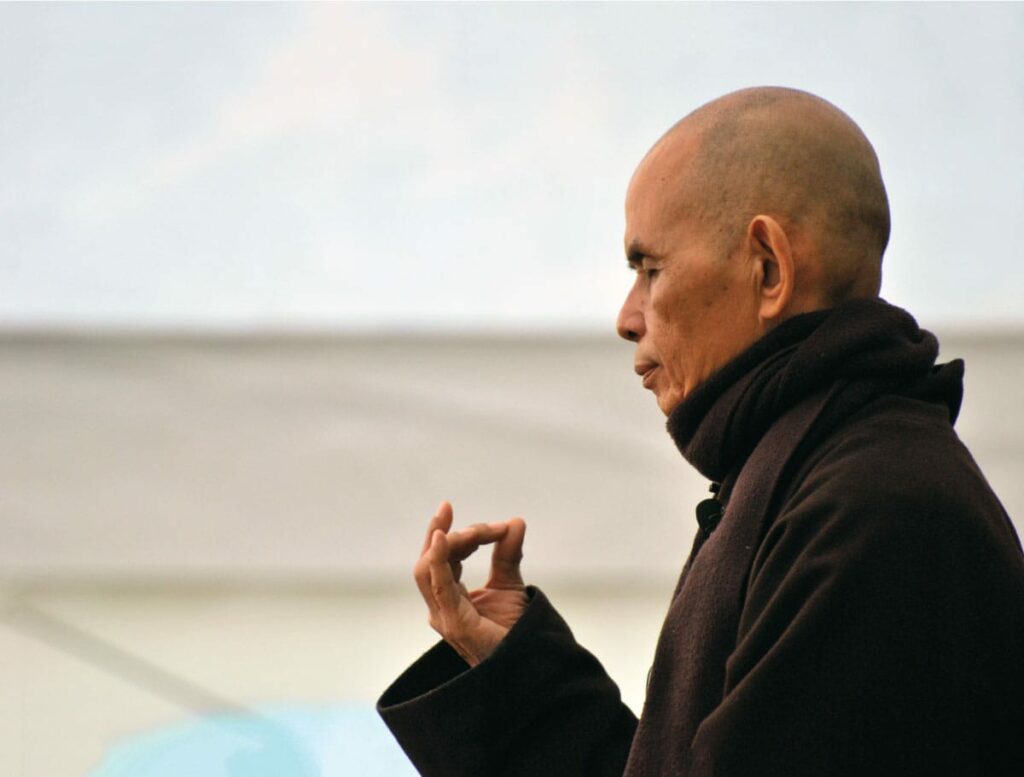

These less superficial forms of “happiness,” however, are only aids to the ultimate aim of Buddhism, which is freedom or liberation from striving to achieve a permanent state of comfort for ego, which is, according to the first noble truth, the very cause of our samsaric suffering (dukkha) in the first place. As the late Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh writes, “One of the most difficult things for us to accept is that there is no realm where there’s only happiness and there’s no suffering. This doesn’t mean that we should despair. Suffering can be transformed.”

Happiness Identified as a Goal Within Buddhism

Some teachers—including His Holiness, the 14th Dalai Lama, in his now classic 1998 bestseller, The Art of Happiness, written as a dialogue with psychiatrist Howard Cutler—express “happiness” as a goal of all people, including Buddhists: “I believe the very purpose of our life is to seek happiness. That is clear. Whether one believes in religion or not…we are all seeking something better in life…the very motion of our life is towards happiness.” He goes on to say that happiness in the Buddhist context is based on mind training, which identifies pathways that lead to suffering and those that lead to happiness, primary among those that lead to happiness is working for the benefit of others. The way to make others happy is to practice compassion. The way to make yourself happy is to practice compassion.

In the pali canon, and therefore within Theravada teachings, various forms of what has been translated as “happiness” are identified. Sukha (covering a range of meanings, including joy and bliss) is a frequent term and is distinguished from preya (sensual happiness). S.N. Goenka, teaching in the tradition of the Burmese teacher U Ba Khin, writing in a paper called “Is the Buddha a Pessimist?” described how the Buddha presented a range of forms of sukha, starting with happiness derived from wholesome worldly pursuits, culminating in ultimate forms of happiness: “Restraint of mind brings happiness…Guarding one’s mind brings happiness…The practice of Dhamma brings happiness.”

Happiness as Problematic

Some teachers believe that emphasizing happiness can counteract the effort needed to work toward genuine liberation—freedom from suffering—which includes regularly and rigorously challenging our self-cherishing ego, including the desire to be happy. In his book, Not for Happiness, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche writes, “So if you are only concerned about feeling good, you are far better off having a full-body massage or listening to some uplifting or life-affirming music than receiving dharma teachings, which were definitely not designed to cheer you up. On the contrary, the dharma was devised specifically to expose your failings and make you feel awful.”

Likewise, Zen teacher Barry Magid, in his book Ending the Pursuit of Happiness: A Zen Guide, asks readers to consider whether their “pursuit of happiness” is the very source of our suffering, including spiritual practice and self-help that tries to root out everything that is wrong with us and create a new, better, happier version of ourselves. “Zen,” he writes, “…is telling us that our search itself may embody the very imbalance we are trying to correct, and only by leaving everything just as it is can we escape a false dichotomy of problems and solutions that perpetuates the very thing it proposes to fix.”

Related Reading

5 Practices for Nurturing Happiness

Thich Nhat Hanh’s life was inspiring, his benefit great, and his teaching, like the dharma itself, profound and practical. Here, he shares five practices to nurture happiness: letting go, inviting positive seeds, mindfulness, concentration, and insight.

10 Ways to Find True Happiness

Introduced by Kaira Jewel Lingo, ten Black dharma teachers dive deep into the paramis, the ten qualities of enlightened beings.

Is happiness really the central goal of Buddhist practice?

Anushka Fernandopulle, Ven. Thubten Chodron, and Kaira Jewel Lingo discuss the real meaning of “happiness” in Buddhism.

Not for Happiness

Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse tells us that if it feels too good, it’s probably not Buddhism. If you want real, honest painful, transformation, then read on.

Buddhism A–Z

Explore essential Buddhist terms, concepts, and traditions.