Eihei Dogen (1200–1253) was the founder of the Soto school of Zen. He is referred to by a variety of names, including Dōgen Zenji, Dōgen Kigen, Kōso Jōyō Daishi, or Busshō Dentō Kokushi. He began the first Japanese Zen lineage that survives to this day.

An orphan of aristocratic parents, Dogen received monastic ordination at age 13 at Enryaku-ji on Mount Hiei. This was the primary monastery of the Tendai school, the dominant Buddhist tradition in Japan at that time. While still a teenager, he began Zen training in Kyoto with Ryōnen Myōzen (1184–1225), the dharma heir of the Rinzai teacher Myōan Eisai. When he was 23, he traveled to China with Myōzen. In China, he received dharma transmission from Tiantong Rujìng (1163-1228), a Chan master of the Caodong school.

After Dogen returned to Kyoto in 1227, he wrote the first version of “Fukanzazengi,” or “general advice for the principles of zazen,” as Zen meditation is called. A revised version written in 1233 is chanted in Soto Zen temples to this day. “Fukanzazengi” has been called Dogen’s manifesto challenging the Buddhist establishment of Japan. It was also the first essay or “fascicle” in the primary collection of his work, the Shobogenzo, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye. Today, Shobogenzo is considered one of the greatest philosophical works of the Japanese language.

In 1233, Dogen moved into a temple on the outskirts of Kyoto that belonged to his mother’s family. This temple was renamed Kannondori Koshohorin-ji, or Koshoji for short. This was the first true Zen temple in Japan, remodeled in the manner of Chinese Chan temples. Sometime later, he left Kyoto to establish another temple, Eiheiji, in Echizen province on Japan’s west coast. Eiheiji was dedicated in 1241, and Dogen taught there for the remainder of his life.

Dogen’s Key Teachings

The Tendai school in which Dogen trained as a young monk had adopted a doctrine called hongaku, “original enlightenment.” This teaches, as Mahayana Buddhism generally teaches, that enlightenment is the fundamental nature of all beings. However, the Tendai school had decided that there was no need for disciplined meditation to actualize this inherent enlightenment. Dogen questioned this, and after his time in China, he returned to Japan, certain that zazen, Zen meditation, was essential.

Enlightenment is inherent, Dogen wrote in “Fukanzazengi,” but our delusions and our selfishness get in the way and cause us to suffer. Since the Buddha sat in meditation to realize enlightenment, he asked, why do we not need to do the same? Dogen also emphasized the unity of practice and enlightenment. Zazen is not something you do that will lead to enlightenment, he taught; it is enlightenment itself, unfolding in each moment.

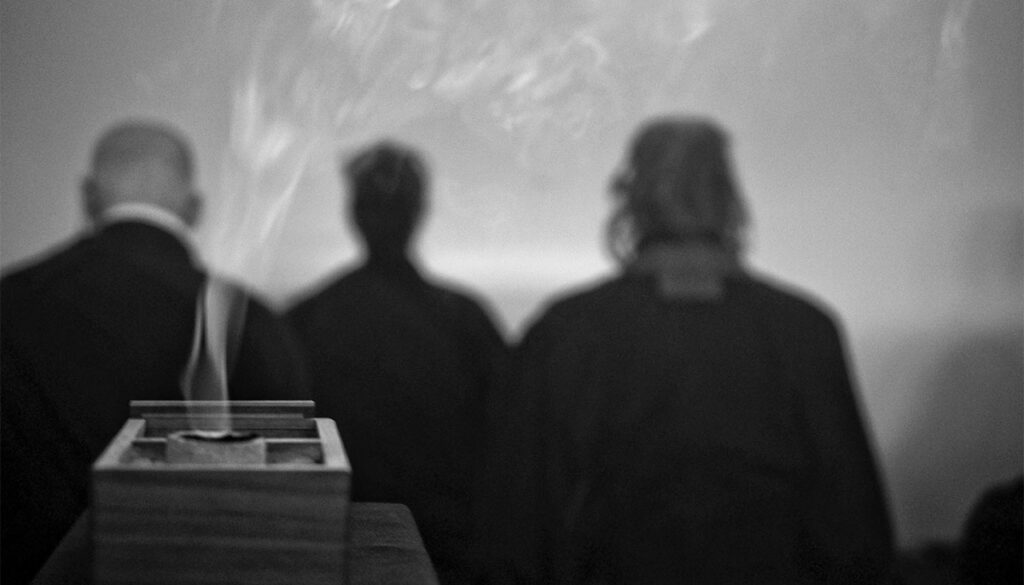

Dogen became a fierce advocate for shikantaza, or “just sitting” meditation. Contemporary Zen teacher Taigen Dan Leighton calls shikantaza “the dynamic activity of being fully present.” In shikantaza, one sits without an object or goal in mind, because seeking a goal reinforces the illusion of a separate self that is missing something.

Dogen’s voluminous writings describe made facets of practice and enlightenment and challenge everything we think we know about ourselves and reality. But the importance of shikantaza is the most essential point.

Related Reading

Dogen’s Instructions to the Gardener

Karen Maezen Miller on cultivating the three minds—joyful mind, kind mind, and great mind.

Dogen, the Man Who Redefined Zen

From just sitting to cooking as practice, Dogen defined how most of us understand Zen today. Steven Heine on the life and global impact of Dogen Zenji.

Dogen’s 4 Key Teachings

From being to the nature of time, Dogen explored the big questions. Four experts unpack some of his most influential concepts.

Notes on Dogen’s “Being–Time”

The title of Uji, translated as “Being–Time,” essentially contains the totality of the text. Unpacking the meaning of this hyphenated word opens a vast interconnecting vista of practice. The two characters u-ji are usually translated as arutoki or “for the time being.” Dogen separates the two characters (u meaning being, and ji meaning time) and…

Dogen’s Instructions for Zazen

Shine the light inward. Body and mind will drop away. A meditation instruction from Eihei Dogen, one of Buddhism’s greatest teachers.

Becoming the Mountains and Rivers

When we know something intimately, taught Dogen, it ceases to exist and so do we. John Daido Loori Roshi examines this teaching.

Buddhism A–Z

Explore essential Buddhist terms, concepts, and traditions.