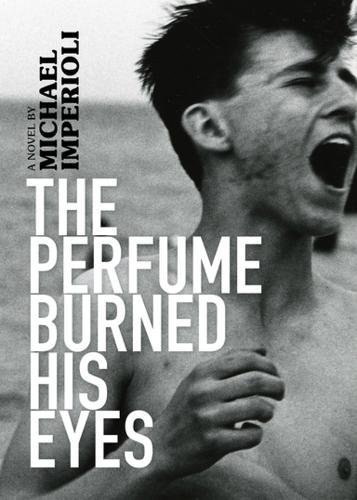

Lou Reed and his girlfriend probably never befriended a sixteen-year-boy struggling with the loss of his father, but in his novel The Perfume Burned His Eyes Michael Imperioli imagines what would have happened if there had been such a friendship. The story that unfolds is dark and touching by turns, and also subtly infused with the dharma.

Imperioli, who’s best known for playing Christopher on The Sopranos, was friends with the late Lou Reed. In his final years, Reed was a student of Mingyur Rinpoche, and Imperioli is likewise a Vajrayana Buddhist. In this interview, I ask Imperioli about his meditation practice, his creative process, and the Lou Reed he knew. –Andrea Miller

Andrea Miller: How did you first meet Lou Reed?

Michael Imperioli: He lived in the Village and so did I when I was in my twenties. Very often I’d see him walking around the street, so a couple of times I spoke to him briefly as a fan.

Around 1993, I got cast in I Shot Andy Warhol as the character Ondine, and at a Knicks game at Madison Square Garden I saw Lou Reed on the escalator. I was like, oh, this is an opportunity for me to talk to Lou. The problem was I knew he hated that they were making this movie because it was about this crazy woman who practically murdered his dear friend Andy Warhol. But I figured what the hell. So I went up to him and said, “Hi, I’m a really big fan and an actor, and I got cast in this movie that I know you’re not happy they’re making.” He went, “I think it’s despicable.” I said, “Yeah, I know, but I’m an actor and I’m playing Ondine.” He just scoffed and turned his back. I felt like shit, but then he came back over and said, “Listen, do your work, have a good time.” And he turned away again. Probably in that little exchange was the seed of the book because I saw that nastiness [he was known for], but also there was compassion at the same time.

What was Lou like?

As an artist, but also as a person, he evolved over time. His work toward the end of his life was very potent. He made such an impact early on and was always tied to that, but that bothered him. He never shied away from his music of the past, but he didn’t like to be tied to his persona of the past.

Rachel was a transgender woman that he lived with at one point in his life. After they broke up, he never spoke publicly about her ever again. In interviews in the early seventies, he talked about being a gay man. Then in the eighties he married for the second time and he married for the third time in the 2000s. So there were different phases of his life, and Lou didn’t like being pinned to any one of them, at least publicly.

For me writing is writing, just like running is running, and meditation is meditation.

Those are some of the things that I admired about him—he was always searching and evolving. There’s nothing worse than someone who has this reputation and then clings to it till they’re eighty years old, even though it’s a reputation that’s more appropriate to someone who’s twenty-five. Lou never became just a nostalgia act playing his hits.

What inspired you to write The Perfume Burned His Eyes?

I had a few bad attempts of writing books, then I started writing this coming of age story in 2013 as a way to relate to my own son who was sixteen at the time and going through what sixteen-year-olds go through. So, I started writing about this kid and I set it in the seventies in New York, which is a little before my coming of age period, but it’s a period of New York that I’ve always found interesting artistically and have a certain nostalgia about. Then about three months into my writing, Lou passed away and it hit me on a couple of levels. There was the fact that I did know him, and he was always very generous and kind to me. And also, his passing marked the end of an era to me, both in the sense of his art and also what he represented about New York. It just hit me to put [Lou and my coming of age story] together and that really became the engine to get me through writing this book.

At one point, your fictionalized version of Rachel, Lou Reed’s girlfriend, talks about karma. Is there any other way in which the dharma informs The Perfume Burned His Eyes?

One of the things that draws me to artists is if they’re able to put a sense of compassion into how they look at their characters. My favorite novelists always bring a sense of compassion for the human condition. I hope that some of that comes into the book.

The book also explores the theme of perception and misperception, even paranoia.

That’s where all the suffering comes from—from not seeing reality, not seeing the truth for what it is. On a macro level, we’re all very much connected. And that connection is much more profound and true than the small perception of separateness and being an island unto ourselves. That’s where all the confusion comes from—the conflict and cruelty and pain. It’s easier said than done to live from a place of seeing the bigger picture.

There are people who say that writing is their meditation. For other people, running or cooking or something else is “their meditation.” What do you think the statement that writing is a form of meditation?

I’m not going to judge anybody’s definition of anything, but for me writing is writing, just like running is running, and meditation is meditation. Sitting on the cushion is a very specific process. I think the goal is to bring what you’ve learned in meditation into your life. You tame your mind so you can deal with the world in a more controlled way, that is, you’re not swayed by negative emotions all the time.

In your book, Matthew, the narrator, says that both Lou and the character Veronica have “acute sensitivity to human fragility.” How do you define this acute sensitivity, and do you have it, too?

In a sense, all artists have that. That’s what [Matthew] is really tuning into, because Veronica is definitely an artist. She writes and she’s already defined herself as an artist. I think the character of Matthew is going to go on to be an artist, but at that point he hasn’t really figured that out yet.

I think that sensitivity is what makes great artists, and it’s that same sensitivity that causes an unbalance in artists and why some of them don’t live too long. Some of them get wrapped up in drugs and alcohol and all kinds of addiction. So, it was really his perception of that quality that these two people shared and realizing that he is drawn to that quality in people, but not understanding why yet.

How do you think that quality can be managed so it doesn’t destroy people?

Sometimes it’s just luck. Lou Reed was always thought of as the rock star that was going to OD, even more than Keith Richards in the early seventies. He was taking so many drugs and was so messed up that people were convinced his death was imminent. Sometimes it’s just a matter of what somebody’s body is able to tolerate.

But sometimes it’s the commitment and drive to create that that gives you the survival, and then sometimes it’s being able to find some other ways of living, like becoming a Buddhist or finding some other kind of spirituality or bigger picture that transcends the material world.

What feeds your creativity?

It’s people really—people who I’m close to, people I’ve never met, and people who I’ve had small exchanges with. Relating to other people and trying to understand them and the way they impact me has always been one of my main driving forces of creativity.