“Are you studying the religion of wokeism or the religion of Buddhism?”

“Perverting the dharma with identity politics.”

“Keep playing the victim.”

“Sheer nonsense.”

This is some of the blowback I’ve got from my work challenging racism and promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in Buddhism. While much of the response to my research has been positive, it has also been the target of defensiveness and derision from some white Buddhists, and resentment and rage from others.

I have been attacked personally and accused of being a “pseudo-scholar” and of “attempting to pervert the dharma by means of identity politics.” Self-identified alt-right Buddhists (yes, there is such a thing) have gone as far as creating a podcast ridiculing me and two other Buddhist Studies scholars for our work on racial justice in American Buddhism.

The white backlash against my scholarship on racial justice echoes many of the responses that Buddhists of color encounter when they attempt to make their communities more inclusive. Buddhists of color who are pioneering racial justice initiatives report that some white Buddhists denied that racism existed in American Buddhism, and told them they were imagining racial harm and exclusion. Others declared that Buddhists of color were not real Buddhists and accused them of being “too angry” and trying to “divide the sangha.”

In other words, as feminist Sara Ahmed explains, racism and white privilege aren’t the problem. It’s the people who name racism and white privilege who are the problem. For me, the experience of being at the receiving end of white resentment and rage has only strengthened my connection with Buddhists of color and empathy for what they experience, and deepened my commitment to anti-racist work as an essential part of both my scholarship and Buddhist practice.

To understand the backlash against racial justice initiatives in American Buddhism, we only need to look at larger social and cultural patterns. In her award-winning book White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, African American historian Carol Anderson shows that African American advances toward inclusion and equity have been met with white reactivity and resistance ever since the passing of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865. From the replacement of slavery laws with Jim Crow segregation laws to the replacement of Barack Obama by Donald Trump, white Americans have sought to preserve and reproduce their cultural dominance and power.

So, it would be a surprise if Buddhism in the United States were completely free of this backlash against racial equity and inclusion. Yet many non-natal Buddhists come to the tradition with romantic and naive ideas. They imagine that Buddhism is a peaceful spirituality free from conflict, and that meditation practice will be a solution to all of their problems. Such practitioners often find it hard to accept, let alone confront, the reality that racism, sexism, and other forms of abuse exist in their communities.

The late John Welwood, a Tibetan Buddhist and psychologist, coined the term “spiritual bypass” to identify how many practitioners use Buddhist practice to avoid psychological developmental issues and emotional conflicts. Insight Meditation teachers Sebene Selassie and Brian Lesage extend Welwood’s concept to identify “cultural spiritual bypass”—the use of Buddhist practice to avoid the social realities of racism, white supremacy, sexism, and gendered violence.

The Buddhist resistance to racial justice work shows us the three poisons in action. The backlash—aversion—to Buddhist racial justice initiatives makes visible both white Buddhists refusal to see things as they are—ignorance—and their refusal to give up how they benefit from systems of whiteness—greed. But while Buddhism is not immune to racism, it does offer us the potential to respond differently.

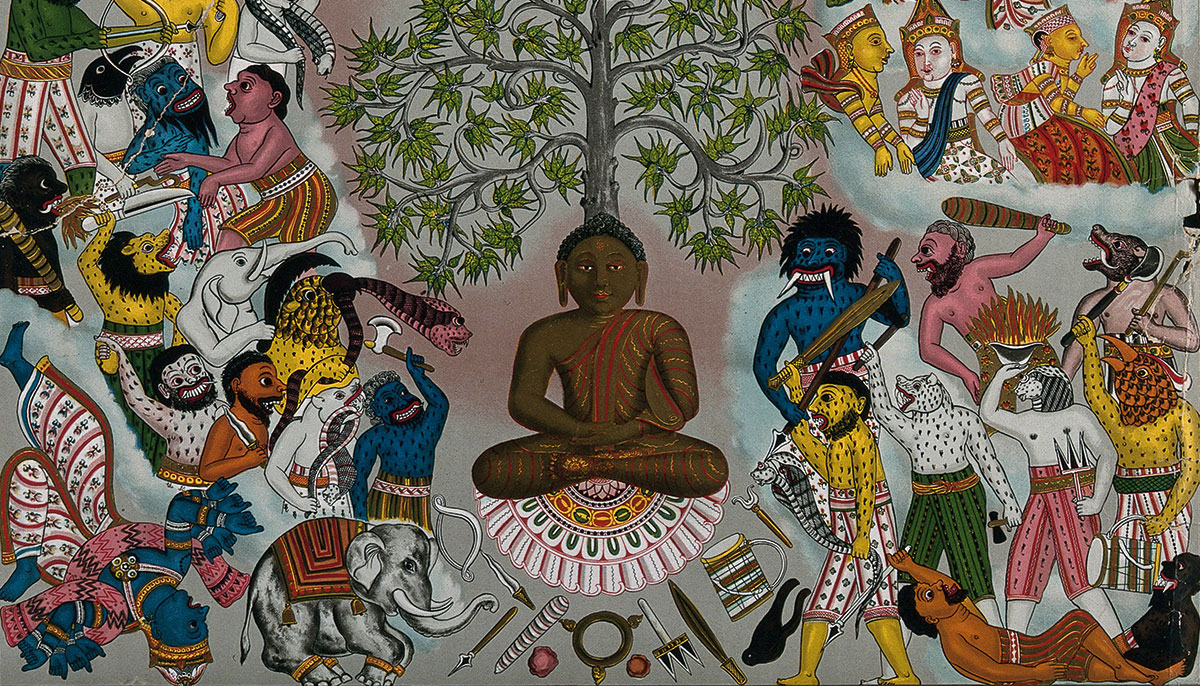

Joy Brennan, a fellow Buddhist scholar–practitioner, and I recently gave a collaborative workshop on “Collective Liberation: Theory and Practice,” at Zen Mountain Monastery, which explored racial justice work from a Buddhist perspective. We identified whiteness as a manifestation of the demon Mara, the personification of the three poisons.

We talked about the importance of naming Mara in its multiple, evolving forms, and how the Buddhist philosophy of Yogacara provides helpful tools for recognizing and being liberated from the harmful conditioning of whiteness.

The white backlash to racial justice progress inside and outside of Buddhist communities has reminded me as a

Buddhist scholar and practitioner that Mara doesn’t give up without a fight. Like Siddhartha sitting under the Bodhi Tree resisting the threats and temptations of Mara, we must remain firm in our resolve and name Mara’s armies for what they are—reactionary forces rooted in ignorance, aversion, and greed that aim to maintain the status quo and keep us ensnared in cycles of suffering.