Question: Buddhism as a whole speaks eloquently on issues such as managing suffering and dealing with violence after it has occurred, with forgiveness, acceptance, and letting go. But, in my experience, it has been largely silent on dealing with issues of violence as they are occurring. So, here is my question: In day-to-day society—be it in a business setting, family setting, or more public setting—we often witness mistreatment such as emotional violence, bullying, and disenfranchisement being perpetrated against ourselves or others. Does the dharma provide any teaching on how to deal with this kind of situation—not after it has happened, but while it is happening? Should we respond and, if so, how should we respond?

I ask this question because it seems that we are often advised to take the “nonviolent” approach, which is often interpreted as taking a passive, nonreactive approach.

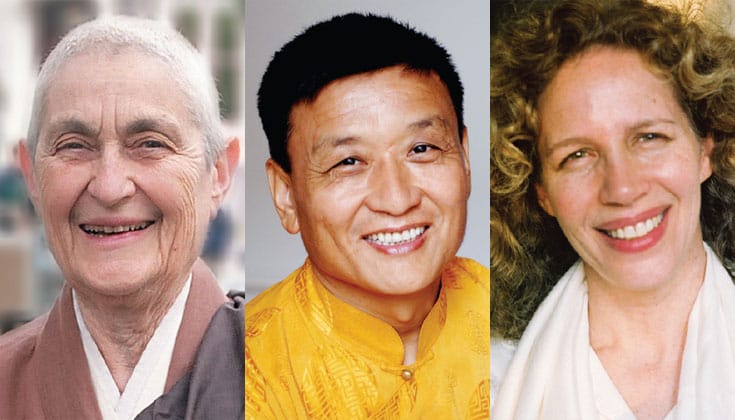

Narayan Helen Liebenson: There are two instances in the Buddha’s life that are instructive regarding your question. The first involved a drunk and angry elephant running toward the Buddha with the intent to kill him. The Buddha responded by sending the elephant metta, whereupon the elephant stopped in his tracks and bowed down instead of trampling the Buddha to death.

In the second instance, the Buddha was subjected to angry insults. First the Buddha just listened to the man, then he basically said he could not accept the anger, that it was a gift he would not receive.

So yes, we need to respond in the moment to any mistreatment of ourselves or others, but the question is how.

The Buddha taught that violence begets violence and that only love can stop the cycle, so it is important to avoid participating in violent actions. But this doesn’t mean lying down and passively accepting abuse. Nor does it mean demonizing the person who is causing the trouble or seeing that person as the “other.”

Nonviolence does not equal passivity or nonresponsiveness. It means bringing forth the qualities of heart we are training ourselves in, namely, loving-kindness, courage, patience, and wisdom, and doing our best to enact them in the heat of the moment. Pausing to be mindful of just one breath can help calm the mind. Calmness offers the possibility of responding out of wisdom and compassion, rather than out of anger.

Standing up to injustice and preventing those who are causing harm from continuing to do so can be an expression of love and compassion. It protects not only oneself and others but the perpetrators as well by preventing them from being harmed by their own unskillful actions.

Our conditioning tells us to fight or flee but the dharma tells us to stand our ground and be aware of the emotions being stirred up, and then to take the wisest and most compassionate action possible in a given situation. Of course, the wisest action may be to fight (without anger) or to flee (without fear). What would it mean to fight or flee without self-centered aggression and because it’s the sensible thing to do?

In unjust situations, this can be extremely difficult to do. Sometimes the only thing we can do is be patient and try not to make a situation worse until a beneficial and creative action becomes clear.

Because this is such a difficult arena, it’s extremely beneficial to learn skills for meeting violence with nonviolence. The Buddha’s guidelines for wise speech can provide invaluable skills. These include practicing speech that is truthful, kind, unifying, and useful, and letting go of speech that is untruthful, unkind, divisive, and indulgent. Also, Marshal B. Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication (NVC) approach provides language and communication tools that are in line with the Buddha’s teachings.

It’s important to recognize the power of our individual actions, no matter how small they may seem. In the face of suffering, it is easy to feel overwhelmed and helpless. It is possible to slide into passivity and even indifference. Dharma practice encourages receptivity not passivity, and equanimity not indifference. Of course, we can never know how we will act in a given situation until we are actually in it and we act out of whatever wisdom and compassion is available to us in the moment.

Zenkei Blanche Hartman: A monk asked Yun Men, “What is the teaching of the Buddha’s whole lifetime?” Yun Men replied, “An appropriate response.” I have also heard this translated as “Teaching facing oneness” and I have been told that the characters literally read “one meets one,” or “each meets each.” In a situation such as you described, I think it means to be totally present in order to discern if there is a way to intervene without escalating the violence.

As for the Buddha’s teaching on stopping violence, you might read “Angulimala Sutta: About Angulimala” online at accesstoinsight.org. Although the Buddha called on some supernatural powers to get Angulimala’s attention and to prevent Angulimala from harming him, he clearly said to Angulimala, “You must stop your murderous ways.”

In the ninth precept of the Order of Interbeing, founded by Thich Nhat Hanh, is the teaching, “Have the courage to speak out about situations of injustice even when doing so may threaten your own safety.” And the twelfth precept is, “Do not kill. Do not let others kill. Find whatever means possible to protect life and prevent war.”

When you ask “Should we respond?” and “How should we respond?” you are bringing up the teaching of the Buddha’s whole lifetime of practice and his response to “just this” or “things-as-it-is,” as Suzuki Roshi used to say. Our whole life of practicing the buddhadharma is to study how best to respond to whatever we meet with wisdom and compassion. My teacher often says, “Respond, don’t react.”

We cultivate the four immeasurables (loving-kindness, compassion, empathetic joy, and equanimity) and the six paramitas or “perfections”—the virtues perfected by an awakening being in the course of their development: dana paramita (generosity), sila paramita (discipline or precepts), kshanti paramita (patience or forbearance), virya paramita (energy or exertion), dhyana paramita (meditation), prajna paramita (wisdom)—all to be able to respond to whatever we may meet in the most beneficial way. Moreover, the first pure precept is to refrain from all harmful actions.

So my answer to you is: Yes, we should respond to everything we encounter with an open and loving heart, without anger or judgment, trying to connect with the Buddha in the person we are responding to. Falling into old habits of anger and judgment just puts us in a hell realm along with those who may be perpetrating the violence. I appreciate a prayer of the great teacher Shantideva, “May those whose hell it is to hurt and hate be turned into lovers bringing flowers.” And I try to heed the warning of Mark Twain, “Anger is an acid that can do more harm to the vessel in which it is stored than to anything on which it is poured.”

So you have raised a big question. How shall we respond? How shall we respond to life in each moment? Learning nonreactivity and calmness is the teaching of a whole lifetime, so we need not be discouraged if we are not sure what to do, or how to intervene to resolve an angry or violent situation. Asking oneself these questions means that compassion and kindness are already established. At times, one’s calmness alone will make an impression; at other times, one might need to call the police or Child Protective Services. In order to make the most skillful response we need to stay awake and stay present and connected as much as we can in each moment. Above all, bring compassion to violence, even when it is directed at you.

Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche: According to dharma teachings it is more a question of how to act rather than whether to act. There is no encouragement to be either passive or active, but there is guidance on action. We can speak of actions of body, actions of speech, or actions of mind. One’s actions of body should occur from a deep, grounded stillness. One’s actions of speech should be connected to deep inner silence. One’s ideas or solutions should come from an open, spacious mind. Even in response to violence, these actions are not driven by fear or anger; rather, they are actions that arise spontaneously with confidence and awareness. When awareness is present, you know what to do. Your actions are healing, not harming.

When your sense of stillness, silence, and spaciousness is obscured by internal distress, it is not the time to act. Let me give an example in the realm of action through speech. Perhaps someone has criticized you and you feel you have been disrespected and misunderstood. You write an email to clarify the situation, but you notice your words are sharp and cutting. You feel almost powerful as you write angry words, and there is a sense of relief as you express yourself. Fortunately you do not press the send button, but save your response as a draft. The next day you reread the email and edit it a bit, deleting some of the sharper points of your attack. Again you save it. A few days pass, and by the end of the week you no longer feel the need to send the email. Instead of pressing the send button you delete the email. To qualify as a true healing this has to be more than an example of giving up or letting go because you think that is what you are supposed to do. That only subtly reinforces a worldview where you are a victim and the other person is the aggressor.

What would the internal scenario look like if this were truly a healing transformation? As a practitioner of meditation, as you spend time connecting with openness and the awareness of that openness, you become aware of the hurt and anger that motivated your initial response. As you feel your feelings directly, you host them in the space of being present. You host your feelings because they are there, and hosting means you feel without judging or analyzing further. Interestingly, without elaboration, the drive behind the feelings begins to dissolve into the spaciousness of being present. As you become fully present, the harsh words of the other’s criticism do not fit or define you. It is possible that you may experience them coming from an unbalanced or vulnerable place in the other person.

If you do decide that some action needs to be taken, you have connected more fully with a sense of unbounded space within you. This experience of being fully present is powerful. Awareness of this inner space gives rise to compassion and other positive qualities. It is important to realize that you do not arrive at this experience of yourself by rejecting, altering, or moving away from your feelings, or by imposing some prescription of how to behave, or by justifying your feelings by thinking or elaborating upon them. As you continue to be fully present, the feelings release into the openness. If you are truly honest, they no longer define your experience of yourself. Can you trust that this is your true power?

The space of openness is indestructible. It cannot be destroyed; it can only be obscured. Having connected with yourself in this way, whatever you write or communicate will be influenced by that respect and the warmth that marks being fully present. Because you have treated your own reactivity by simply being present, you have come to a trustworthy place in yourself.

In this example, the process took you a week, but as you become more familiar with the power of openness, it can happen in an instant. Even strong negative emotions can be a doorway to direct and naked awareness—a doorway to the direct connection to the space of being. If you meet the moment fully and openly, awareness will define what you do. Awakened or enlightened action will spontaneously arise; it does not come from a plan.

Even physical or verbal actions that may appear forceful arise from the confidence of openness itself and the power of compassion that is always available and always benefits all.