Belligerent bohemian punk poet. Street-hot rock and roll messiah. Ultimate female rock rebel. The Queen of Piss. That was the Patti Smith of the 1970’s.

Mother of two. Widow. Poet and performer. Student of religious imagery. Author. That is the Patti Smith of 1996.

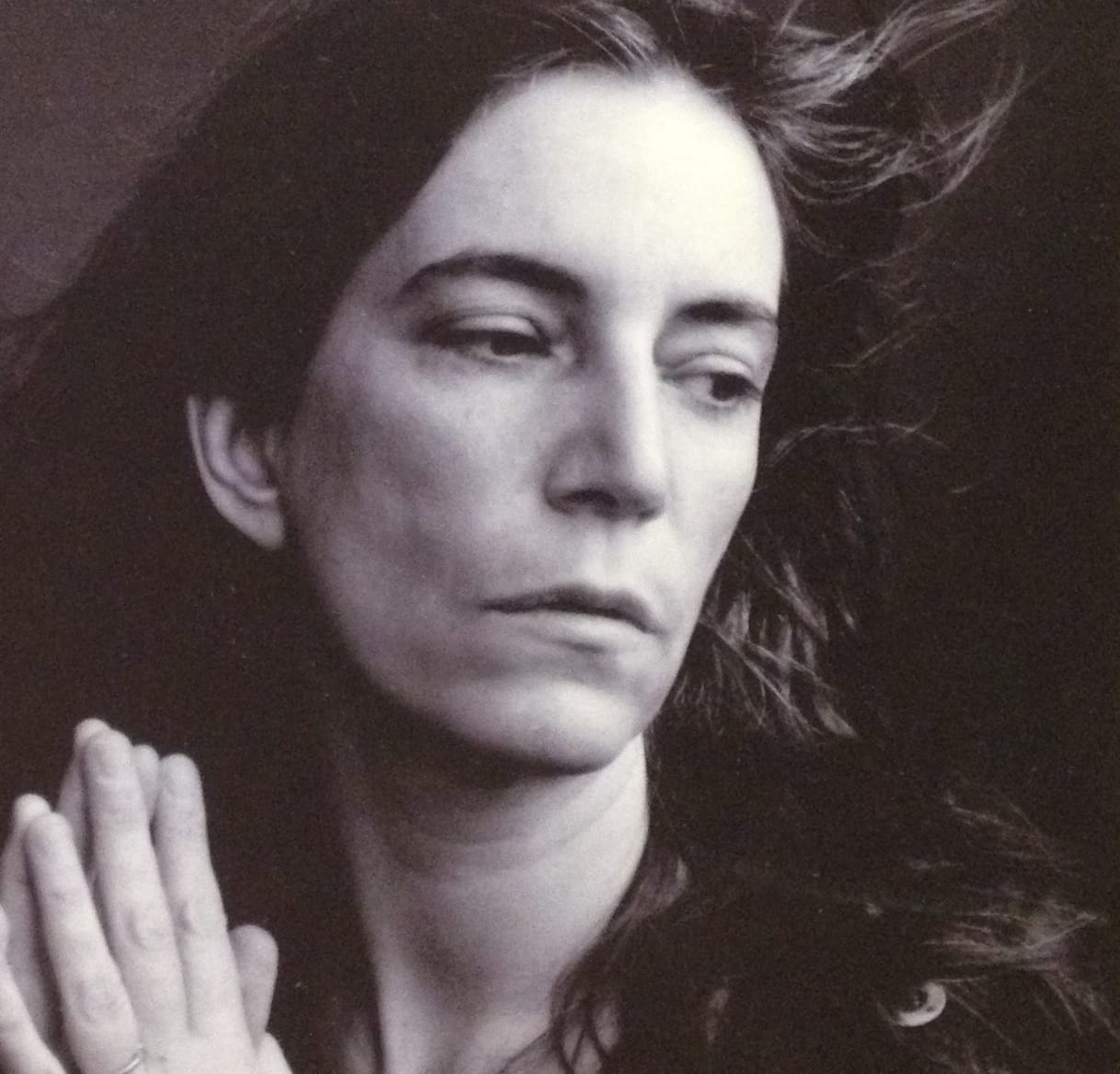

“I feel like a very youthful and a very ancient person,” Smith, 49, says. She still has the rail-thin body of 20 years ago, but her dark hair shows gray.

“To me, I look like I’m 12 years old but with ancient hair. I can still taste what it’s like to be a child. I can still feel the intense pain and embarrassment of being a teenager. I still have a streak of rebelliousness in me that is unwarranted and unnecessary. I still have some youthful hopes. But I possess a certain amount of resignation and weariness.”

Much of that resignation and weariness comes from living with the sorrow of death. Her husband of 18 years, Fred “Sonic” Smith, guitar player for the hard rock band MC5, died of a heart attack in 1994 at the age of 44. A month after her husband’s death, her beloved brother Todd died of a stroke. Robert Mapplethorpe, her best friend, died of AIDS, as did several other close friends. Richard Sohl, the original Patti Smith Group piano player, whom she deeply adored, died of heart failure at age 37.

“I find that sorrow breaks the heart open, makes you more vulnerable,” she says. “In some ways sorrow is a beautiful state. It can heighten one’s sense of humor. You can find strength and clarity in sorrow. Sorrow is a gift. You have to treasure it. The important thing is to honor it.

“Sorrow is like a precious spring. Every once in a while you can drink from it, but you can’t let it consume you. Sorrow, like drugs, or love, or our own gifts, can be both dangerous and beautiful.”

When I spoke to Patti Smith recently, she sat, one foot tucked under her, in the music room of her 100-year-old house. On one side of the room stood her husband’s old upright piano. A bust of Beethoven, his idol, sat on the piano.

Smith stepped out of the rock and roll spotlight in 1979. She moved to this Detroit suburb, raised two children and concentrated on writing. She stepped back on stage in 1995, performing with Bob Dylan and doing solo gigs. Her book Coral Sea, sixteen prose poem meditations on the death of Robert Mapplethorpe, is scheduled for release in late May, and her new album, Gone Again (Arista), is to be released in June.

The new album, for which she wrote all the songs, was planned with her husband before his death. Going ahead with recording the album was difficult, Smith acknowledged, and much of her grieving process permeates the album.

“When I lost my husband, I felt completely desolate,” she said. “From him I learned a more compassionate view of the general populace. He was much more compassionate about those who will inherit the earth than I. But after he died, I did the best work I have done in fifteen years. The quality of my singing has strengthened. That’s my legacy from my husband.”

She shifts in her chair. The narrow, pointed lancet windows, the whitewashed walls, and the dark wood ceiling give the room the mood of a secular monastery. On one wall hangs a scroll of a seated Buddha. A Tibetan sack containing two of her favorite books, What Remains of a Rembrandt by Jean Genet and Painting and Guns by William Burroughs, dangles from a nail. What appear to be rosary beads, but on closer inspection is a rope with knots and beads, stands out starkly against the white wall where it is displayed. Mapplethorpe, a close friend and professional collaborator for more than twenty years, made it for her.

Out of her experience of so many deaths, Smith has discovered the ability to commiserate and communicate with her departed loved ones.

“I feel some of their best strengths,” she said. “I find myself gifted, enhanced, a richer person, because I have magnified aspects of them within me.”

After the shock of losing her brother subsided, she felt that her heart “if it had been a piece of coal, became a beautiful ember. I could feel my heart going from being completely ice to going warm. I felt joy. I knew that my brother was in my heart. I was almost laughing because I recognized that was my brother, who was the embodiment of brotherly love. I find now that I have a lot more patience. I am more apt to take a breath and forgive someone for something, or be more philosophic about the actions of others.”

She began performing again after her brother’s death. “It was his great wish that I perform,” she said. “Right now it’s good for me, a good test. I really wasn’t sure that I was capable of performing again or how the people would respond. I think I won’t be doing it for a long time, perhaps some months. Then I’ll be ready to write again, which is what I really want to do.”

She shed no tears on the morning Robert Mapplethorpe died. Those had been spent during his long illness. Instead, she went into a two-month frenzy writing the prose poems that appear in Coral Sea. “That was my way of weeping for Robert,” she said. “In keeping with our friendship, he would rather have that than tears anyway.”

Although best known as a singer and performer, Patti Smith considers herself first a poet and writer. As a child, she was inspired by Louisa May Alcott. Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Child’s Garden of Verses and the Psalms deeply affected her. William Burroughs, Arthur Rimbaud and Federico Garcia Lorca were other literary influences. She credits the French Surrealist painters, the sculptor Constantin Brancusi and the French actor Jeanne Moreau with shaping her sensibilities. The language of the Old Testament, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, and other spiritual scriptures captivated her.

As a child Smith had the mark of an artist, if being an outsider is a requisite for that calling. She was born in Chicago but grew up in Pitman, New Jersey, a small industrial town not far from Philadelphia. Her father was an intellectual and factory worker, tap dancer and former track star. Her mother was a “talented waitress.” At the age of seven, Smith was forced to wear an eye patch as the result of scarlet fever and tuberculosis. Scrawny, self-conscious, shy, patched, she thought of herself as “creepy looking,” as did the other kids. She was a social outsider who learned to play a wicked game of pool.

She developed a vivid internal fantasy life fed by the Bible, UFO magazines, and the elves and fairies in Yeats’ poems. She recorded her dreams and visions in a small notebook that she carried as automatically as other girls carried a doll. At sixteen, she worked in a factory before entering Glasboro State Teachers College on a scholarship. She found college too much a strict container and fled by bus to Manhattan, where she worked in a book store.

There she lived in the Chelsea Hotel, that infamous den of artists, in 1968 when Burroughs, Joplin, Slick, Hendrix, Reed and many of Warhol’s “Factory” crowd were in residence. She quickly became one of them.

Her first major book of poems, Seventh Heaven, was published in 1971. By 1973 she had become a punk literary cult figure and a year later formed her band, the Patti Smith Group. Their 1976 album Horses was hailed by England’s New Musical Express as “better than the first Beatles’ or Stones’ albums, better than Dylan’s first and as good as The Doors and The Who and the Velvet Underground.”

In the song “Rock-and-Roll Nigger,” the refrain, “Outside of society is where I want to be,” staked out Smith territory.

“I had contempt for society when I was younger,” Smith said, reflecting on those early artistic years. “That’s why I wanted to be outside society, although it is not as true now. If I want to be outside society it’s merely because that’s where I’m the most comfortable and can do the most good. I’m not a social animal. I’ve always felt estranged from people, but that’s not putting myself above them. I was much more serious about it when I was younger. Now I have a lot more sense of humor about it.”

The artistic condition is a mixed blessing for Patti Smith. “It is like a gift and a plague,” she said. “I experience an inner beauty and clarity. Then it gets pulled, like a rug from beneath my feet. It’s like God talks to me and then stops talking. At a certain level, I definitely feel I am a mouthpiece.

“The pursuit of poetry or, for lack of a better term, a worthy piece of work, is like being on a crusade, on a mission. When I feel in my heart that I’ve attained it, it almost feels like I’ve been knighted by God, anointed in some way. This is, of course, followed by complete self-doubt.

“In my creative process I build walls in order to tear them down. In the process of tearing them down, I’m building up another piece of work. The work goes out to the people and the artist is left empty-handed. In that, the work is sometimes secondary. The process can be considered ennobling only after the work is done. During the process it is just hard work.”

Smith described her cycle of creating as a “wrenching, exquisite process. It’s almost like the artist becomes a wriggling caterpillar over and over and over, then evolves into a butterfly over and over again. To feel that moment of emerging, to feel that beautiful moment, the artist has to go back to the wriggling, sort of disgusting state again.

“A true artist goes out and returns. Rimbaud talks of the derangement of the senses and of the return. The idea is that an artist doesn’t explode his or her mind. You spin out as far as you can, but you do return. You must return and articulate where you’ve been, or you’re not an artist. Without that sense of responsibility, you are a person tripping out. An artist is, by nature of the process, going to keep pushing to go further. But at the same time they must stay in control or run the risk of losing contact with the work.”

The 14-minute song “Radio Ethiopia” (1977) is an example of how Smith goes out and returns with the goods to create something new. The song has been described as a total insurrection against structure, but Smith disagrees.

“The piece was improvised but it was structured,” she explained. “It began as a rock song, opened up into chaos, and came back with beauty. We performed that piece with the same concentration and desire to go out and return as Coltrane’s band explored new space and returned. Coltrane was a great guiding force for me. I studied him and had my band study him.”

The song was inspired by Rimbaud’s last letter to his sister written the day before he died. He was in the French port of Marseilles desperate to return to Abyssinia (Ethiopia), where he had lived in the southern town of Harare. He beseeched his sister to find stretcher bearers to get him onto a freighter leaving for the Horn of Africa. Yet he knew he would never see Abyssinia again.

“He wrote in that note, ‘I am unable to do what I must do. The first dog on the street can tell you that’,” quoted Smith. “The song was exploring Rimbaud’s state of mind at that moment when he experienced perhaps the last bit of excitement in his life-the hope of returning to Abyssinia-while realizing that he wasn’t going anywhere except where God was going to take him.”

As part of the continuous reexamination of her art, the ancient artist Smith continually balances herself with the youthful artist Smith. In the introduction to Early Works, a reprint of her work from the 1970’s, she wrote, “In art and dream may you proceed with abandon. In life may you proceed with balance and stealth.” The introduction was meant as a warning sticker, without being an apology, for her romanticizing of sex and drugs in those “early works” of the 1970’s.

“Early Works had its own code but not necessarily a moral code, especially in regard to sex,” Smith said. “The work in the seventies was done in a completely different climate than that of today. We were exploring what we perceived as new terrain without giving thought that those coming behind us might get hurt by following our lead.

“I feel a certain responsibility to put a balance to what we did then. Robert and I talked about that before he died. He said that, in all good conscience, he’d have to think about doing the same kind of work as he did earlier, given the impact of AIDS. One has to be careful how you impart to a new generation the lessons you’ve learned.”

Smith admitted that when she was younger, she was very snobbish about the artist, the monk, the priest. “To me, all beauty and honor was reserved for them. As I’ve gone through life-had children of my own, seen the sacrifices that the so-called ‘common man’ makes every day-I’ve had a very different take on ordinary courage. I no longer feel that I am more blessed or have a more honorable position than, say, a person who spends his or her life in a hospice taking care of the dying.”

Smith is now slowly returning to writing after an 18-month period during which she could neither write nor pray. “I think a lot of that was just weariness,” she explained. “When I was younger, I would have been quite horrified to go a whole year without writing. I would have thought that it was over, that my muse had flown, that God no longer talked to me, that I had suddenly become ordinary. But I’ve learned to accept such gaps. They’re very humbling. I have to sit very quietly and wait. Until I feel fully entered again, I won’t be doing the vast bodies of work that I did in the 1980’s.”

Smith, who was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, learned to pray from her mother. “That opened for me a whole new world. The idea that there was a higher aspect that I could pray to seemed expansive.” She tries not to overwork prayer; when she does pray, she asks for abstract things, like strength to cope, for peace, and, occasionally, for illumination.

“I try not to petition the higher power any more,” she said with a smile. “When I do, I don’t ask for miracles. When Robert was dying, I prayed that he would be able to face death stoically. I didn’t ask that he be spared or even not suffer physically. Just that he would be able to handle what was dealt to him in his last days.”

She once prayed for Tibet to be in the news. She was 12 years old and had been given a school assignment to report on a country throughout the year. She chose Tibet and prayed that the country would become newsworthy. China invaded Tibet.

“I felt tremendously guilty,” she recalled. “I felt that somehow my prayers had interfered with Tibetan history. I worried about the Dalai Lama. It was rumored that his family had been killed by the Chinese. I was quite relieved when he reached India safely. I vowed to always say prayers for his safe-keeping, which I have done.”

Smith met the Dalai Lama in September, 1995, at the World Peace Conference in Berlin. “I learned quite a bit from that man,” she told me. “He had to be constantly putting things in balance, constantly adjusting. He would stand in front of a large body of people and project and magnify his joys and hopes so that all those people would be smiling. He was able to make each person feel radiant. But he had to protect himself and do what he must do.”

Smith’s concept of the Tibetan culture was that the people’s prime mandate was to pray for the planet, for mankind, and for the perpetuation of life.

“The idea that they seemed to pray continuously, that there were prayer flags, prayers written on rocks, along mountain sides, and prayer wheels everywhere-it seemed to me that the Tibetan people’s whole life was directed by prayer. I thought that was really beautiful. It makes me feel quite protected,” she said.

In 1994, she wrote this poem for the Dalai Lama:

a small entreaty

May I be nothing

but the peeling of a lotus

papering the distance

for You underfoot

one lone skin

to lift and fashion

as a cap to cradle

Your bowing head

an ear to hear

the great horn

a slipper to mount

the temple step

one lone skin

baring this wish

May Your hands be full

of nothing

May your toys

scatter the sky

tiny yellow bundles bursting like stars

like smiles

and the laughter

of a bell