Venerable Tenzin Palmo is best known as the British nun who meditated in a Himalayan cave for twelve years, as described in the popular book, Cave in the Snow, by Vicki MacKenzie. Though she left retreat in 1988, she still finds herself describing that solitary life to others, and sometimes defending it. Her one request in granting this interview was: “Please, let’s not talk about the cave.”

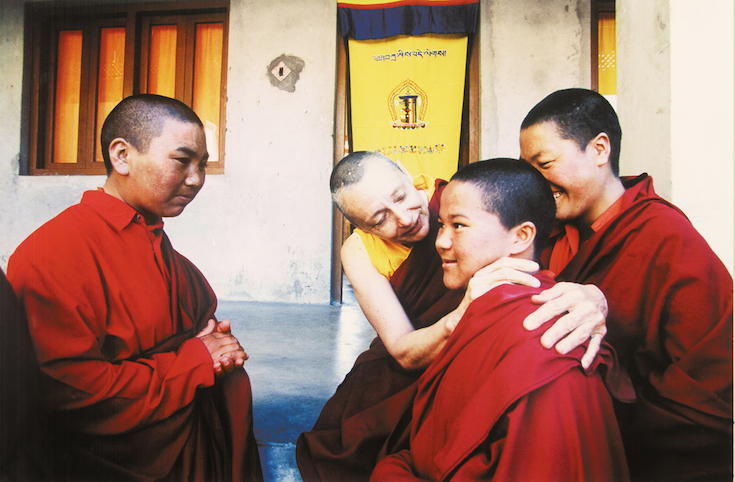

Born in London, Tenzin Palmo was drawn to Buddhism from an early age, and in 1964, at age twenty, she sailed to India. There she met her guru, the eighth Khamtrül Rinpoche, and became one of the first Western women to be ordained in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Before he passed away in 1980, Khamtrül Rinpoche asked Tenzin Palmo to start a nunnery, a request echoed more than a decade later by the lamas of his monastery in Tashi Jong in northern India. In 1993, Tenzin Palmo committed herself to the task of building a nunnery for women from Tibet and the Himalayan border regions. She now lives most of the year in Tashi Jong, where she has set up temporary quarters for the Dongyu Gatsal Ling Nunnery. There she trains and educates nuns who might not otherwise have the opportunity to devote their lives to the dharma. She is also committed to reviving the tradition of female yogis, or togdenma, the training for which is “long, rigorous, and austere.” Several months of the year, Tenzin Palmo travels to raise funds for the nunnery, which is still under construction.

One might imagine someone like Tenzin Palmo—someone who was drawn to such extreme solitary practice—as aloof or somehow disconnected. On the contrary, she is easy to talk to, funny, opinionated, and surprisingly worldly. While her wisdom illuminates difficult concepts like rebirth and merit, what is particularly refreshing is her passionate devotion to her bodhisattva vow—“to genuinely benefit other beings, endlessly, endlessly, endlessly.” As she makes very clear, “It’s not a quickie.”

—Bethany Saltman

How do you understand your rebirth as a female in England?

Well, it wouldn’t have been very much use being reborn in Tibet. I mean, look what happened to Tibet. It made a lot more sense, I think, to be born in the West. Why I got reborn as a female, I don’t know, but I think in my past life I must have had some sympathy for the female. But I certainly wasn’t a female last time, which was why I felt so strange in a female body when it first came.

When “it” first came?

I mean that I didn’t understand why I was in this body. When I heard that our bodies change when we got older, I thought, “Oh good, now I’ll get back to being a boy again.” But it didn’t happen like that. Now I’m glad that I’m female. I think we females have a lot of work to do for other females. So it’s good to have a female body this time.

So what do you know of your past life?

Not much. I’m not really interested. Definitely I was a disciple of my lama, which is why faith arose on just hearing his name. The day of my twenty-first birthday, he came to the Young Lamas’ Home School, where I was teaching English. I was very excited. But when I went in to see him, I was so frightened that I just stared at his feet, at his shoes. I couldn’t even look at him. So I had no idea what he looked like, whether he was old or young, fat or thin. I just knew he was my lama. I must be the only one to ever ask a lama to give them refuge without knowing what the lama looked like.

When I did look at him, I had a very strong feeling of meeting someone whom I had known for a long time. It felt like, “Oh, how lovely to see you again.” The deepest thing inside of me had suddenly taken external form. It was very strong and very simple at the same time. I never doubted, for one second, that this was my lama. Nor did he. So when I said I wanted to take refuge, he just said, “Of course,” even though we had just met. And when I said I wanted to become a nun he said, “Of course, of course! What else would you like to do?” He also said that in past lives he was always able to keep me very close to him, but that in this lifetime, as I had a female body, it would be more difficult.

It was very painful when my lama died, incredibly painful. He was only forty-eight, so we weren’t expecting it.

How did he die?

He had heart problems, and he died in Bhutan. When Tibetan lamas die they stay in a realization of clear light nature of the mind for several days or weeks, and so he was in samadhi for quite some time while they worked out where his body would be taken. During that time the body is sitting up in meditation and it becomes very youthful and beautiful.

Did you see him like that?

I didn’t, because he was in Bhutan, but I have seen other bodies in samadhi; the body often gives off a very beautiful perfume and doesn’t decay at all. It remains perfect. And apparently, though I have never myself felt it, if you feel the heart region, it’s still warm. The brain is dead, but the heart region is still warm and the body stays very beautiful. If you pray and meditate in the presence of a person in samadhi, it’s a great blessing because at that time the lama’s mind is in a state of the clear light nature of death. Tibetans are very skillful at that. They have many teachings on how to die consciously, and how to remain in the clear light. It works—you can see it. They can stay in that state for hours, days, or weeks.

What is it like for you to work with your teacher in his next incarnation, now that he’s a different person, a young boy?

He’s not such a young boy anymore; he’s twenty-four. But he is a different person. He’s very quiet, very grounded, very centered. He doesn’t speak much. There are times when he is just there, as a lama, and then suddenly he looks at me and [snap], my whole body is filled with an electric current and a sense of certainty.

When you met him for the first time, what were your feelings? Did you have trouble relating to him as a child?

I was afraid to go and see him. He was not quite three years old. I was very frightened, partly because I was sure that when he saw me he would think, “Oh, what a funny-looking thing,” and burst into tears, and then I’d feel upset.

Because you’re a woman?

Yes, because I am a Western nun and he had never seen one, and I was concerned how a child would react to something strange. I kept putting it off and then finally I thought, I’ve got to go see him. So I went up and, as I was prostrating, he looked at me and said to his attendant, “It’s my nun! It’s my nun! Look, look.” He was jumping up and down and laughing and so happy. I burst into tears! [Laughs] I was the one who started crying, and then he became worried because I was crying, so tears started running down his cheeks. The two of us were just a riot. We then spent the whole morning playing together and we had a great time running around. His attendant later told me he was a very quiet child, who usually didn’t play with strangers.

He had his own little seat with a table in front, where he would sit cross-legged. When people came he would just sit there, often for hours, and he wasn’t even three yet! He would bless them and give them food. His attendants said they hadn’t taught him this. When people left, he’d ask, “Have they gone?” They’d say, “Yes, Rinpoche,” and then he’d get down and start playing with his toys. When somebody else would come, he’d drop his toys and go and sit back down again. You can’t teach someone that, not at that age. There’s an inherent knowing what to do.

When you see these genuine incarnations when they’re tiny children, and see how much they already know, how much they remember, how much they are lamas, then you really have to believe in this whole tulku system. It’s not just training. If you see young tulkus when they’re with other young monks, it’s like in a Broadway show or something, where the main character is spotlighted and the others kind of fade into the background. You think, “Who is that tulku?” Because that’s all you see, even though they’re all dressed the same and they’re all the same age. It’s like the tulku is illumined. They don’t look like the other ones.

Why are they all boys?

I asked my lama that and he said that his sister, at the time of her birth, had more auspicious signs than he did. You know, Tibetans have a big thing about signs when the mother is pregnant and at the time of birth. He said, “My sister, when she was going to be born, had more signs than I did, and everyone got very excited. Then when it was a girl, they said, ‘Oops, mistake.’” Now if she had been a boy, they would have looked after her, sent her to a good monastery, tried to find out who she was, and so forth. She would have been properly trained and been able to benefit other beings. But because she was a girl—with the way things were in Tibet—she was nothing. She was ignored. She wasn’t educated. Instead, she was married off at the right time. He said this happened again and again. He said, therefore, because of the social culture of Tibet, it just didn’t make sense to come back as a girl. The only way girls could come back and actually have a chance was to be reborn in very high lama families. That way they could get education and training and eventually function as lamas. But ordinary women wouldn’t have that opportunity. Even as nuns they don’t have the opportunity because they’re not educated.

So were people mistaken about your lama’s sister?

No, I think it was a tulku trying to break the mold. But you can’t.

Do you think it will ever be broken?

Certainly in the Tibetan communities in exile, the girls are being educated the same as the boys. And now the nuns are being given the same kind of monastic education as the monks. So if there is someone with potential, hopefully it will flower and they will have the kind of training that will enable them to benefit others. But still, almost all the tulkus being born are men.

At Zen Mountain Monastery we are studying one of Master Dogen’s fascicles, Jinzu (Spiritual Power), and the whole sangha is wrestling with this right now. The question that Daido Roshi keeps putting to us is this: Layman Pang said that my wondrous functioning is chopping wood and carrying water. So the question is, what’s the difference between somebody who is chopping wood and carrying water as activity that needs to happen to keep the fire burning, and someone who does that as a realization of spiritual power?

I think the difference is that when an ordinary person drinks tea, we just drink tea. When an enlightened being drinks tea, that being drinks tea from a state of recognized primordial awareness, and that’s very different. Someone once said to me, “How is that when you and I and drink coffee, we just drink coffee, and when Rinpoche drinks coffee, it’s buddha activity?” It’s true. If you’re in the presence of a genuine master, without even doing anything the master affects you at a profound level. It’s natural, spontaneous activity. Buddha activity doesn’t mean radiating light and elevating yourself up a thousand feet in the air. That’s not the point. The point, as Zen is always saying, and Tibetans understand this very well also, is that every activity becomes perfect buddha activity. And anyone sensitive feels that at a very profound level.

Do you think this kind of awareness is particularly difficult for Western students?

I think the problem with Western students is that they’re very ambitious. One needs to learn the path without the goal—the feeling that wherever you are, that’s where you are and, at that moment, it is a completely perfect place to be. Enjoy the flowers at your feet. Western Tibetan Buddhists are always looking out at the distant snow peaks and they lose sight of the flowers along the path. It’s buddhahood or bust! Actually we’ve got countless lifetimes, so relax.

I would like to ask you about the bodhisattva vow. You said in one of your talks that the only way the bodhisattva ideal can work is if we have the understanding of many lifetimes. But if we say we have many lifetimes, can this lead to practitioners saying, “Well, I guess I don’t really need to work too hard”?

No, we have to work very hard at it, because this precious life is our opportunity. It’s important to realize that the coming together of so many forces at this time is very rare. We’re human beings, and that in itself is a rare opportunity. We are not one of the millions and millions of other beings that are not human. So here you are, you are a human being. You’re educated. You’re in a country where, despite everything, you do have the freedom to practice what you want to practice. You have met with the dharma. All these are very rare events.

If I were to say, “Forget it, I give up,” what might happen in my next lifetime?

Who knows where you would be reborn? If you lose interest in the dharma you might be reborn anywhere in the world, and not in a place where you are likely to meet with the dharma again. And then what? Then you’re completely off the path.

How is the dharma’s understanding of merit different from thinking that if I’m a good girl in this life, then I will go to heaven?

But we don’t want to go to heaven. We want to be reborn so that we can keep going and realize the dharma so as to benefit other beings endlessly. It’s a very different thing. We’re not collecting merit scores for ourselves. We’re making merit so that we can be reborn in a situation where we can really live to benefit others, and ourselves, again and again and again, more and more and more every time. We are in a position to deepen our understanding to be of genuine benefit to other beings.

What is your understanding of merit in terms of being a monastic or a layperson?

I think it’s a meritorious action to become a monk or a nun, provided that your motivation is pure. If you become a monastic because you think it’s an easy life, because you’re going to be fed and sheltered and people will respect you, then that is not a very meritorious motivation. If you become a monk or a nun because this will give you the freedom to study and practice and benefit both yourself and others, then that is a very meritorious action.

Do monastics accrue more merit than someone who decides to stay a layperson because she thinks she will benefit more beings working in a hospital, or a school?

I do think that when someone decides to devote oneself entirely to spiritual life, that that is more meritorious.

And working in the world with children, with people who are ill, you don’t see that as dharma activity?

It is dharma activity, but the problem is our inherent ignorance keeps us in samsara and unable to really, on a deep level, benefit ourselves and others. For example, some students went to Milarepa and said, “We should stop living in caves and meditating and instead go out and help beings as bodhisattvas.” Milarepa replied that as long as space exists, so long will there be beings for you to help. First you have to help yourself. So, for example, say you wanted to be a doctor and you think to yourself, “I’ve got all these beings. They’re sick, they’re dying, and I’ve got to go out and help them.” Then you grab a bag full of scalpels and medicine and rush off. But even though your motivation is very pure, you end up harming beings because you don’t know what you’re doing. If you say, “No, I can’t take time to study, all these beings are dying, I’ve got to go out and help them,” your motivation is good but it lacks wisdom. However, if you take the time to really study how to be a proper doctor, then there are endless beings out there whom you could help.

So from a Buddhist point of view, the first thing is to help yourself, to get your own mind together, and to really understand how to benefit beings, not just on the physical level, but on all levels. Then there are endless beings you can benefit.

In terms of merit, what about the koan where Emperor Wu asked Bodhidharma, “What merit have I attained?” And Bodhidharma said, “No merit whatsoever”?

That’s from the point of view of emptiness, where there is neither merit nor no merit.

And so, what about that?

Yes, from the point of view of emptiness there is neither being nor non-being. But we’re not dealing with the point of view of emptiness; we’re dealing with the point of view of our relative being. Our relative being is what rules our relative world. So from the point of view of the relative world, merit is very important, because merit clears away obstacles. Why do some people, when they want to practice, keep coming up against problems and obstacles—inner and outer obstacles? It’s because of the lack of merit. Merit soothes things; it clears you. It’s like oil that gets things working nicely.

I feel I’ve had many incarnations since I was born thirty-five years ago. That is my understanding of rebirth—that it’s happening constantly.

That’s also true. We’re reborn every second, every moment. It’s on many levels.

And what about the feeling that I am not a completely different person than I was yesterday? Is that my delusion?

That is ego-clinging, yes. But on a relative level, you need to have a sense of identity; otherwise you’d fall apart, wouldn’t you? To be enlightened doesn’t mean you end up stupefied and unable to function.

So what does it mean?

[Sighs] To be completely enlightened means that you’re a buddha. I don’t speak of enlightenment.

Has anybody been completely enlightened since the Buddha?

There are certain people who some think are enlightened. The problem with the word “enlightenment” is what you mean by it. A Zen master gave an example, which Huineng and others would have repudiated, but it explains what we mean by enlightened and enlightenment. It’s about using the mind as a mirror, and having dust. This is a good example because it shows what we’re talking about. If you put a little pin in the middle and you make a little space, a little circle, then the nature of the mirror shines through. Now you know the mind is not dust, that behind that dust there is this mirrorlike nature of the mind. If it’s a big enough hole, you might be so transfixed by the hole that you don’t notice the rest of the dust. So you think you’re enlightened. But as my lama said, when you realize the intrinsic nature of the mind, then you start to meditate. That’s not the end; it’s the beginning. It’s only when all the dust is gone from the mirror, and there is only mirror, that we’re really enlightened. So that’s a lot of work. Some people get very deep experiences and they think they’re enlightened. But that’s not enlightenment; that’s just some realization. Realization is wonderful, but you have to expand it until there’s not a single defilement left in the mind and the mind is completely open and spacious. Even in that condition, you still use the relative mind. The Buddha himself said, “I still use conceptual thinking, but I’m not formed by it.”

How do you think you have affected the world by re-entering after many years in retreat and sharing your knowledge with us?

I don’t think I’ve changed anything, but I hope that by my talks I have encouraged people in their practice. That’s as much as any of us can do. Most of the people I talk to are not going to go off and live in a cave. Why should they? So I talk about how people can stop separating dharma practice—going on retreats, going to dharma centers, hearing talks, reading books—from family and social life, which they consider ordinary, mundane activity. We need to transform those ordinary, daily activities into dharma practice, because otherwise nothing is going to move. It’s very important to realize that with the right attitude, a little awareness, and skillful means, we can transform everything—all our joys and sorrows. The dharma is every breath we take, every thought we think, every word we speak, if we do it with awareness and an open, caring heart.