When we drop fear, we can draw nearer to people, we can draw nearer to the earth, we can draw nearer to all the heavenly creatures that surround us.

—bell hooks

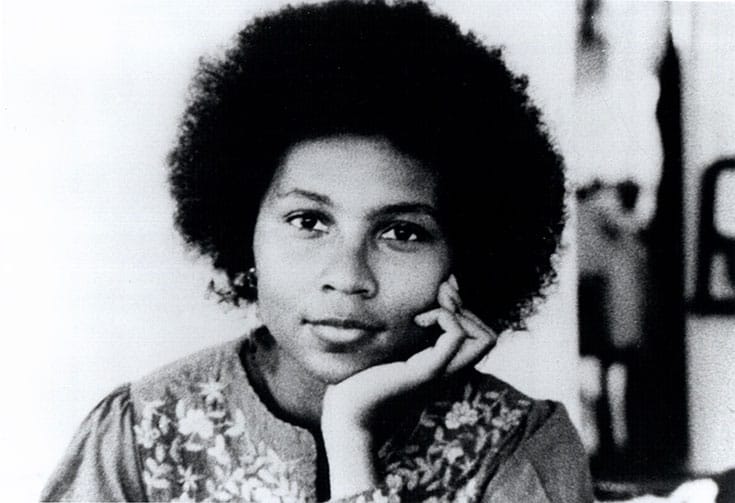

Writer, feminist theorist, and cultural critic bell hooks has played a vital role in twenty-first-century activism. Her expansive life’s work of writing and lecturing has explored the historical function of race and gender in America.

hooks’ writing is deeply personal and educational, drawing on her own painful experiences of racism and sexism in an effort to educate us on how to combat them. hooks also plays a part in the Buddhist community, drawing inspiration from Buddhist practice in her life and her work. Her conversations with a number of important Buddhist leaders have been published on Lion’s Roar, along with her reflections on spirituality, race, feminism, and life.

Read on to learn more about bell hooks’ life and work, and to read some favorite pieces by and conversations with her.

The life of bell hooks

Early Life and Education

bell hooks was born Gloria Jean Watkins in the fall of 1952 in Hopkinsville, Kentucky to a family of seven children. As a child, she enjoyed writing poetry, and developed a reverence for nature in the Kentucky hills, a landscape she has called a place of “magic and possibility.” Growing up in the south during the 1950s, hooks began her education in racially segregated schools. When schools in the south became desegregated in the 1960s, hooks faced painful challenges among a predominantly white staff and student population. These would inspire and shape her life’s work fighting sexism and racism to come.

After graduating high school, hooks studied at Stanford University, receiving a B.A. in English in 1973. It was at Stanford, in her Women’s Studies classes, that hooks began to notice a significant absence of black women from feminist literature. She began the writing of her book Ain’t I A Woman during her English studies, and also worked as a telephone operator. In 1976, she earned her M.A. in English from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and later received her doctorate in literature from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1983.

Writing and Career

In 1976, hooks began teaching as an English professor and lecturer in Ethnic Studies at the University of Southern California. During this time, she published a book of poems, And There We Wept, under the pen name “bell hooks” — her great-grandmother’s name, and a woman who, hooks has said, was known for speaking her mind. hooks chose not to capitalize any letters in her first and last name to emphasize focus on her message, and not herself or her identity.

hooks went on to teach at several post-secondary institutions, and in 1981, published Ain’t I A Woman, which examined the history of black women’s involvement in feminism, focusing on the nature of black womanhood, the civil rights movement, and the historical impact of sexism towards Black women during slavery. Ain’t I A Woman went on to gain worldwide recognition as an important contribution to the feminist movement, and is still a popular work studied in many academic courses.

To date, hooks has published more than thirty books, including four children’s books, exploring topics of gender, race, class, spirituality, and their various intersections. In 2014, she founded the bell hooks Institute, in Berea, Kentucky, which celebrates and documents her life and work, and aims to “bring together academics with local community members to study, learn, and engage in critical dialogue.” Visitors to the Institute are able to explore artifacts, images, and manuscripts written and talked about in her work.

Today, hooks continues to write and lecture to an ever-growing audience. In recent years, she has undertaken three scholar-in-residences at The New School in New York City, where she has engaged in pubic dialogues with other influential figures such as Gloria Steinem and Laurie Anderson. Last year, hooks sat down with actress Emma Watson for an inspiring conversation on feminism for Paper Magazine.

bell hooks and Buddhism

bell hooks was exposed to Buddhism due to her love and exploration of Beat poetry — most notably Beat poets Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder. At the age of 18, she met Snyder, a Zen practitioner, who invited her to the Ring of Bone Zendo in Nevada City, California, for a May Day celebration. She has engaged in various forms of what she calls a “Buddhist Christian practice” ever since.

hooks speaks and writes of her spirituality often, and has met in conversation with many influential Buddhist teachers, including Thich Nhat Hanh, Pema Chödrön, and Sharon Salzberg. In a 2015 interview with The New York Times, philosopher George Yancy asked hooks “How are your Buddhist practices and your feminist practices mutually reinforcing?” She responded:

Well, I would have to say my Buddhist Christian practice challenges me, as does feminism. Buddhism continues to inspire me because there is such an emphasis on practice. What are you doing? Right livelihood, right action. We are back to that self-interrogation that is so crucial. It’s funny that you would link Buddhism and feminism, because I think one of the things that I’m grappling with at this stage of my life is how much of the core grounding in ethical-spiritual values has been the solid ground on which I stood. That ground is from both Buddhism and Christianity, and then feminism that helped me as a young woman to find and appreciate that ground…

Feminism does not ground me. It is the discipline that comes from spiritual practice that is the foundation of my life. If we talk about what a disciplined writer I have been and hope to continue to be, that discipline starts with a spiritual practice. It’s just every day, every day, every day.

bell hooks in Conversation

Strike! Rise! Dance! – bell hooks & Eve Ensler

“Where does the trust come between dominator and dominated? Between those who have privilege and those who don’t have privilege? Trust is part of what humanizes the dehumanizing relationship, because trust grows and takes place in the context of mutuality. How do we get that when we have profound differences and separations?”

Eve Ensler and bell hooks discuss fighting domination and finding love.

Building a Community of Love: bell hooks and Thich Nhat Hanh

“In our own Buddhist sangha, community is the core of everything. The sangha is a community where there should be harmony and peace and understanding. That is something created by our daily life together. If love is there in the community, if we’ve been nourished by the harmony in the community, then we will never move away from love.”

bell hooks meets with Thich Nhat Hanh to ask him the question “How do we build a community of love?”

Pema Chödrön & bell hooks on cultivating openness when life falls apart

“The source of all wakefulness, the source of all kindness and compassion, the source of all wisdom, is in each second of time. Anything that has us looking ahead is missing the point.”

In this conversation from 1997, bell hooks talks to Pema Chödrön about how to open your heart to life’s most difficult challenges.

“There’s No Place to Go But Up” — bell hooks and Maya Angelou in conversation

“In my work I constantly say, this is how I fell and this is how I was able to rise. It may be important that you fall. Life is not over. Just don’t let defeat defeat you. See where you are, and then forgive yourself, and get up.”

A classic 1998 conversation between Maya Angelou and bell hooks, moderated by Lion’s Roar editor-in-chief Melvin McLeod.

bell hooks on Sex, Love, and Feminism

Toward a Worldwide Culture of Love

“Imagine all that would change for the better if every community in our nation had a center (a sangha) that would focus on the practice of love, of loving-kindness.”

The practice of love, says bell hooks, is the most powerful antidote to the politics of domination. She traces her thirty-year meditation on love, power, and Buddhism, and concludes it is only love that transforms our personal relationships and heals the wounds of oppression.

Ain’t She Still a Woman?

“It is easier for mainstream society to support the idea of benevolent black male domination in family life than to support the cultural revolutions that would ensure an end to race, gender and class exploitation.”

Increasingly, patriarchy is offered as the solution to the crisis black people face. Black women face a culture where practically everyone wants us to stay in our place.

When Men Were Men

“On one hand it’s amazing how much sexist thinking has been challenged and has changed. And it’s equally troubling that with all these revolutions in thought and action, patriarchal thinking remains intact.”

The message is, says bell hooks, that it’s fine for women to stray from sexist roles and play around with life on the other side, as long as we come back to our senses and stay happily-ever-after in our place.

Penis Passion

“When we finally gave ourselves permission to say whatever we wanted to say about the male body—about male sexuality—we were either silent or merely echoed narratives that were already in place.

bell hooks argues that our erotic lives are enhanced when men and women can celebrate the penis in ways that don’t uphold macho stereotypes.

bell hooks on Life and Faith

Voices and Visions

“When the spirit moves into writing, shaping its direction, that is a moment of pure mystery. It is a visitation of the sacred that I cannot call forth at will.”

bell hooks on the mystery of what calls her to write.

A Beacon of Light: bell hooks on Thich Nhat Hanh

“When I think of Thay now, I am amazed by his awesome gentleness of spirit. Through the years, it’s always been clear that he’s a teacher of tremendous integrity; there has been constant congruence between what he thinks, says, and does.”

The leading cultural critic and thinker bell hooks shares what Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh means to people of color.

When the Spirit Moves You

““Everywhere I turned in nature I could see and feel the mystery — the wonder of that which could not be accounted for by human reason.”

bell hooks shares her experiences of encountering the divine in nature and the written word.

Design: A Happening Life

“When life is happening, design has meaning, and every design we encounter strengthens our recognition of the value of being alive, of being able to experience joy and peace.”

bell hooks Quotes

Living simply makes loving simple.

There is no change without contemplation. The whole image of Buddha under the Bodhi tree says here is an action taking place that may not appear to be a meaningful action.

A generous heart is always open, always ready to receive our going and coming. In the midst of such love we need never fear abandonment. This is the most precious gift true love offers – the experience of knowing we always belong.

It’s in the act of having to do things that you don’t want to that you learn something about moving past the self. Past the ego.

Books by bell hooks

In the Temple of Love: the female buddha

bad baby bell books

In the Temple of Love is a collection of poetry by bell hooks. hooks draws on Buddhist themes of compassion, and puts a particular focus on the female bodhisttva, Tara on the 30 poems in this collection.

Belonging: A Culture of Place

Routledge

“What does it mean to call a place home? How do we create community? When can we say that we truly belong?” asks bell hooks in Belonging. This book follows hooks’ life journey, and what she learned moving from place to place, from country to city, and finally landing back home in Kentucky. hooks explores the “geography of the heart,” touching on issues of race, gender, class, and the roles they play in our sense of community and belonging. hooks takes the reader back to her childhood in the Kentucky hills, where she first developed a deep love of nature, and shows the important role geography can play in developing our spiritual connections and worldviews.

All About Love: New Visions

Harper Perennial

In All About Love, hooks draws from personal experience, and explores the concept and meaning of love through a psychological and philosophical view. She looks closely at the difference between love as a noun, and a verb, examining the flawed idea of love society has created. Drawing on her own childhood and life’s experience, as well as words from influential figures throughout history, hooks investigates the question “What is love?” She unpacks the meaning of love in modern American life, urging us to let go of our obsessions with power and domination in order to truly awaken to love.

Salvation: Black People and Love

Harper Perennial

Here, hooks looks at love in African American communities, urging that we see love as a force for change. She looks at love through both a religious and social lens, again drawing on personal experience, and reflecting on the messages on love displayed in literature, film, and music. hooks also explores cultivating self-love as an African American woman as well as learning to love black masculinity, and embracing heterosexual love. When it comes to seeking justice, and healing historical and modern wounds in the world, and African American communities, “Love,” hooks concludes, “is our hope and salvation.”

The Will to Change: Men, masculinity, and love

Atria

In The Will to Change, bell hooks explores men’s most intimate questions about love, exploring the skewed way patriarchal society has taught men to know love, and know themselves. Though well-known for her feminist thinking, hooks works to include men in the discussion, as she believes men must be involved in feminist resistance. The Will to Change offers a feminist focus on men, doing away with radical feminist labeling of “all men as oppressors and all women as victims.” Many men, says hooks, are afraid to change, and have not been taught how to be in touch with their own feelings — The Will to Change offers a deeply intelligent roadmap to doing just that.