What started as a personal quest for peace by an Indian prince named Siddhartha Gautama some 2,600 years ago has grown into a force for good around the world. Whether you consider it a philosophy, a way of life, or a religion — it is indeed one of the five great world religions – Buddhism and its teachings have been adopted worldwide as a path to less suffering and more happiness.

While Buddhism has many varieties and schools of thought, some teachings and beliefs are universal or nearly so. Let’s look at some of the most essential teachings put forward by the historical Buddha and upheld by those who’ve followed his path of, or prescription for, greater wisdom and compassion.

The Four Noble Truths

The foundational teaching of Buddhism is contained in the Four Noble Truths, which function less as dogma and more as sources of contemplation that could lead one to take up the Buddhist path. These truths are:

- There Is Suffering — Life is characterized by suffering and dissatisfaction. This suffering is inherent to existence and refers to more than physical pain; it is the discontent, unease, and disquiet that are woven into the fabric of life. Even in the best of times, we strive to make good feelings continue and fear that they will not.

- There Is an Origin of Suffering — The root cause of suffering lies in ignorance, which gives rise to craving and attachment—for objects, experiences, attainments. We are focused on enhancing our own self-centered existence.

- There Is a Potential End of Suffering — It is possible to attain the end of suffering by seeing through ignorance and eliminating the ensuing attachment and craving. The cessation of suffering is possible by cutting it off at the root.

- There is a Path to the End of Suffering — The fourth noble truth posits the need to follow a path to repeatedly bring about the cessation of suffering, gradually leading to complete liberation from suffering, enlightenment. The Buddhist path is described in a variety of ways in the various traditions. The earliest and most often referred to description is known as the eightfold path. The different elements of the eightfold path interconnect and reinforce each other in helping practitioners cultivate good conduct, meditative stability, and insight.

Related: The Message of the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths • The Four Noble Truths Are a Plan of Action • No Self, No Suffering

The Eightfold Path

The Buddhist Eightfold Path is composed of eight “right” (or “wise,” or “skillful”) elements or qualities. If we attend to these qualities as we continue with Buddhist practice, we can be said to be engaging to the path in an admirable way. They are:

- Right View — Developing an accurate understanding of reality, including the impermanence of all things and the interconnectedness of life.

- Right Intention — Cultivating wholesome intentions, such as renunciation of what does not bring benefit, compassion, and non-harming.

- Right Speech — Practicing truthful, kind, and non-harmful speech.

- Right Action — Engaging in ethical behavior that avoids harming oneself and others.

- Right Livelihood — Choosing a means of earning a living that promotes honesty, compassion, and non-harming.

- Right Effort — Cultivating the right mental attitudes and putting effort into overcoming unwholesome habitual patterns of mind.

- Right Mindfulness — Developing clear awareness of one’s thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations.

- Right Concentration — Training the mind through meditation to cultivate focus and insight.

Related: Mindfulness and the Buddha’s Eightfold Path

The Three Marks of Existence

The three marks of existence are fundamental concepts in Buddhist teachings that describe the nature of all phenomena and the human experience. They are objects of contemplation that help a practitioner develop a view that will make liberation possible.

- Impermanence (Pali, anicca) — The first mark, impermanence, is the recognition that all things are in constant flux. Impermanence is not limited to physical objects but also applies to mental states, emotions, and experiences.

- Suffering (Pali, dukkha) — The second mark, suffering, is the insight that all experiences are marked by unsatisfactoriness to a greater or lesser degree. Even in the most pleasurable moments, a tinge of fear exists that the pleasure cannot be sustained.

- No-self (Pali, anatta) — There is no fixed, permanent, or unchanging self underlying our experiences. This challenges the conventional notion of an unchanging “I” or “self,” inviting the practitioner to let go of the illusion of separateness and recognize the interconnectedness of all beings and all phenomena.

Related: The Three Doors of Liberation

The Three Poisons

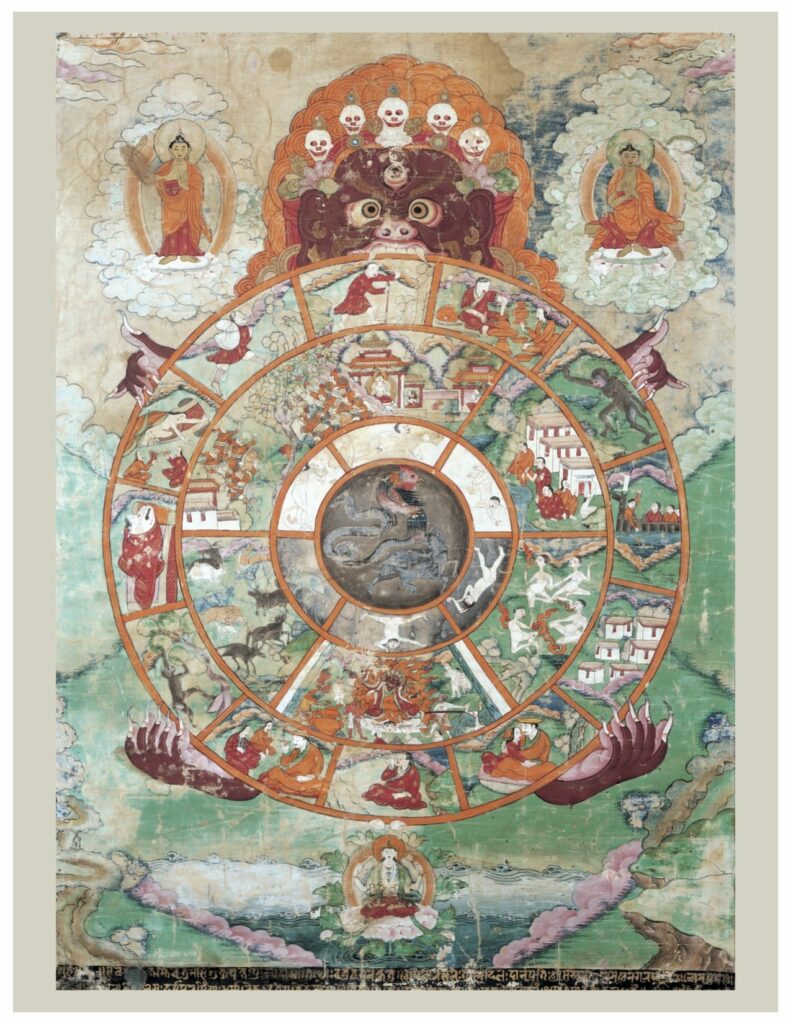

The three poisons are the energy of ego’s three basic attitudes — for me, against me, and don’t care. All unwholesome habitual patterns (Sanskrit, kleshas) are variations on these three themes. Because the poisons drive our suffering, they are traditionally depicted as three animals — a rooster, snake, and pig — at the center of the wheel of life.

- Passion (also called attachment, greed, or lust) — Above all, ego is attached to whatever ensures its survival — physically, psychologically, or spiritually. Whatever feels good, ego wants more of.

- Aggression (aversion, anger, hatred) — Ego will try to repel anything we believe will hurt or threaten us. Because we are willing to hurt others to protect ourselves, even on a massive scale, aggression is the greatest cause of suffering.

- Ignorance (indifference) — This is not the basic ignorance of solidified, dualistic reality that is the foundation of samsara, but it is an active ignoring that enables one to prioritize one’s own pleasure over the suffering of others.

Related: Detox Your Mind: 5 Practices to Purify the 3 Poisons

The Five Aggregates

The five aggregates, also known as the five skandhas, is a schema that describe the various aspects of individuality and help to deconstruct the illusion of a permanent and unchanging self. They are objects of contemplation that help a practitioner gain insight into the nature of reality, the causes of suffering, and the path to liberation. Skandha (Sanskrit) means heap or collection, indicating that these aggregates are simply collections of collections that we take to have ongoing existence.

- Form — The physical aspect of being, conventionally categorized as the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind and all that is perceived by the senses.

- Feeling — The sensations you experience in your body, including all pain and pleasure.

- Perception — You have sense organs, and each of them has objects. Put them together — eye and light, nose and smell, etc. — and you have perception.

- Mental formations — All your concepts and thoughts, from the most mundane to the most grandiose.

- Consciousness — Simply put, this is your ongoing awareness of skandhas 1 through 4.

With reflection and practice, you can begin to understand that all of the skandhas are fleeting. Like all conditioned phenomena, the five skandhas are subject to change and decay. Viewing experience through the lens of the skandhas allows practitioners to loosen the mental solidification that ignores impermanence, egolessness, and suffering.

Related: Beyond Self & Other

Dependent Origination

Dependent Origination, (Pali: paticcasamuppada; Sanskrit: pratityasamutpada) a central tenet of Buddhism, breaks down the intricate web of causality underlying existence. It posits that all phenomena arise in dependence on other factors, encapsulating a chain of twelve interconnected links. These links, beginning with ignorance and culminating in suffering, depict how suffering perpetuates cyclic existence (samsara). Understanding this doctrine is pivotal in breaking the cycle by interrupting the causal chain. It underscores the impermanence and interrelatedness of all things, emphasizing the cessation of suffering through the eradication of its roots. Dependent Origination is a cornerstone of Buddhist philosophy, guiding practitioners toward liberation from suffering and rebirth.

Related: Francesca Fremantle on Dependent Origination

The Three Jewels

Buddhists take refuge in three different expressions of awakened mind: buddha, dharma, and sangha. Each of these is a precious and necessary element of the Buddhist path, and so they are called the three jewels.

- Buddha: the teacher — This refers, first, to the historical Buddha. He was not a god but a human being who provides an example of an ordinary person following a path to enlightenment. More broadly, the buddha principle refers to all teachers and enlightened beings who inspire and guide practitioners.

- Dharma: the teachings — The Buddhist dharma starts with the fundamental truths that the Buddha himself taught—the four noble truths, the three marks of existence, the eightfold path, etc.—and includes the vast body of Buddhist teachings that have been developed in the 2,600 years since then.

- Sangha: the community — The term sangha traditionally referred to monastics in whom lay practitioners would take refuge. In recent times, especially in the West, sangha has come to mean the community of Buddhist practitioners generally, both monastic and lay. Contemporary Buddhists also use the word to describe a specific community or group, and you will often hear people talk about “my sangha,” meaning the Buddhist community to which they belong.

Related: Take Refuge in the Three Jewels • Where to Find Refuge In an Uncertain World • Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem

The Three Trainings

The three trainings are an interrelated set of practices that function together to help practitioners journey to liberation.

- Good Conduct (Sanskrit: shila; Pali: sila) — Practicing good conduct is essential to progressing on the spiritual path. At the most basic level, this involves adhering to the five precepts, which include refraining from killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct, and intoxicants that cloud the mind. In a larger sense, it is the intention to do no harm and to bring about the greatest good for everyone.

- Meditation (Sanskrit and Pali: samadhi) — Meditation — the practice of intentionally working with your mind — is central to much of Buddhist practice. Basic Buddhist meditation starts with practices to help calm and concentrate the mind. From there, a practitioner can begin to investigate the nature of reality and develop insight. The most common form of meditation is breath meditation, in which you rest your attention on your breath. Many schools emphasize other forms of meditation as well as — or instead of — breath meditation, such as chanting, koan practice, and Buddhist yoga.

- Cultivating Insight and Wisdom through Study — Buddhist teachings — such as the Pali canon (the fundamental teachings of the Buddha), Mahayana sutras (teachings on the Bodhisattva path of working for the benefit of others), Zen teachings and commentaries and treatises, and the yogic teachings of the Vajrayana — provide guidance for practitioners, and are referred to as “the dharma” or “Buddhadharma.” Studying helps deepen understanding and insight. Interaction with teachers and with fellow students also helps to sharpen one’s understanding of dharma, enhances one’s meditation, and imparts a more precise view of ethical conduct.

Related: Norman Fischer on Ethics, Meditation, and Wisdom

The Five Precepts

The five precepts are the most fundamental vows that a Buddhist makes. Undertaking and upholding the five precepts is based on the principle of non-harming (Pali and Sanskrit, ahimsa). These guidelines vary in their interpretation, with some practitioners adhering to them strictly and others adopting a more situational approach, guided by compassion and the pursuit of maximum benefit. While diverse sets of precepts exist, the foundation of all Buddhist moral codes consists of the following five root precepts.

- Not Killing — The concept of “not killing” in Buddhism entails the strict prohibition of causing harm or ending the lives of living beings. This encompasses refraining from taking the lives of humans, as well as animals. This precept primarily centers on the preservation of human life, as taking a human life is considered a grave and unforgivable transgression.

- Not Stealing — Beyond refraining from theft, this precept emphasizes the importance of not taking what has not been freely offered or consented to.

- Not Misusing Sex — Modern interpretations of this precept center on one’s conduct in intimate relationships, emphasizing consent and respect for a partner’s feelings as fundamental aspects.

- Not Engaging in False Speech — While minor falsehoods may serve practical purposes, this precept discourages mean-spirited deception and gossip, promoting honesty and integrity in communication.

- Not Indulging in Intoxicants — Whether it pertains to drugs, alcohol, excessive television, or internet use, this precept underscores the need to maintain mental clarity. It encourages individuals to refrain from activities that obscure the clear perception cultivated through Buddhist practice.

Related: The Five Precepts — Buddha’s Training Wheels • The Five Buddhist Precepts for Modern Times

The Brahmaviharas (Four Immeasurables)

The brahmaviharas, often referred to as the “divine abodes” in Buddhism, represent four cherished aspirations and states of mind that serve as a framework for fostering virtuous behaviors while minimizing harmful ones. These states are revered because they are believed to be the dwelling places of enlightened beings. Additionally known as the “four immeasurables” or “four limitless ones,” they epitomize boundless love and goodwill extended to all sentient beings without constraint. They are:

- Loving-kindness (Pali: metta; Sanskrit: maitri) — Genuine love and benevolence, directed not only toward oneself but expansively to all living beings.

- Compassion (Pali and Sanskrit: karuna) — Compassion entails empathetic concern and a desire to alleviate the suffering of others, acknowledging the interconnectedness of all sentient beings.

- Sympathetic Joy (Pali and Sanskrit: mudita) — Sympathetic joy celebrates the happiness and success of others, free from envy or competition, fostering a sense of shared well-being.

- Equanimity (Pali: upekkha; Sanskrit: upeksa) — Equanimity refers to a profound quality of neutrality and evenness of mind undisturbed by emotional upheavals. It is characterized by a quality of not picking and choosing, but rather being content with what presents itself.

Practitioners can bring one or more of the four brahmaviharas to mind at any point during their day to rekindle a sense of loving connection with others. Additionally, these qualities can be cultivated through meditation practices. Initially, individuals stabilize their minds through mindfulness or calm-abiding meditation. Subsequently, they focus on each immeasurable, first directing it towards themselves and then gradually expanding it to encompass all sentient beings.

Related: The Four Highest Emotions

Samsara and Nirvana

Samsara and nirvana are two fundamental concepts that describe the cycle of conditioned existence and the state of liberation from that cycle, respectively.

Samsara, derived from the Pali language, translates to “perpetual wandering” and embodies the unceasing cycle of birth, death, and subsequent rebirth. This relentless cycle persists unless one achieves nibbana (Pali; Sanskrit: nirvana), the ultimate goal of Buddhism. In essence, if we do not undercut the habitual patterns of thought and action that cause suffering, we are bound to repeat them, and perpetuate suffering for ourselves and others.

The concept of nirvana is believed to originate from a world connoting the extinguishing of something. Consequently, nirvana is characterized as the extinguishing or end of the fires fueled by greed, hatred, and ignorance.

Related: What Turns the Wheel of Samsara • Nine Buddhist Teachers Explain Suffering • Cooled, At Peace, Free from Suffering

Karma

The Pali term kamma, more widely recognized as karma in Sanskrit, refers to the law of cause and effect, which governs the moral and ethical consequences of one’s actions. It is a fundamental concept that emphasizes the relationship between actions and their results, both in the present life and in future lives. Karma plays a crucial role in shaping an individual’s experiences and determining their future conditions within the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. This cycle is known as samsara.

According to Buddhist teachings, each deliberate action shapes our consciousness, molding our character, and consequently influencing our conduct, experiences, and ultimately, our destiny. Positive intentional acts, driven by generosity, love, and wisdom, lead to positive outcomes, while negative intentional acts, rooted in greed, hatred, and ignorance, result in negative consequences. The goal of Buddhism is not, however, to simply generate good karma, but to transcend karmic activity altogether. Good karma, however, can create conditions that can foster transcending karma altogether.

Related: Buddhadharma Forum: What Does Karma Mean in Buddhism?

Related Reading

The Four Highest Emotions

Ayya Khema on cultivating loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity.

Detox Your Mind: 5 Practices to Purify the 3 Poisons

Five Buddhist teachers share practices to clear away the poisons that cause suffering and obscure your natural enlightenment.

No Self, No Suffering

Melvin McLeod breaks down the Buddha’s four noble truths and argues it’s not only the ultimate self-help formula, but the best guide to helping others and benefiting the world.

What Turns the Wheel of Samsara

Francesca Fremantle, from her book Luminous Emptiness, discusses the wheel of life and how the Buddha decontructed it.

Mindfulness and the Buddha’s Eightfold Path

To understand how to practice mindfulness in daily life, says Gaylon Ferguson, we have to look at all eight steps of the Buddha's noble eightfold path.

Nine Buddhist Teachers Explain Suffering

Nine teachers explain what suffering is, how we feel it, and why it isn't a condemnation — it's a joyous opportunity.

The Message of the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths

The message of Buddha's Four Noble Truths is that paying attention and seeing clearly lead to behaving impeccably in every moment on behalf of all beings.

Forum: What Does Karma Mean in Buddhism?

Bhikkhu Bodhi, Jan Chozen Bays, and Jeffrey Hopkins discuss the Buddhist doctrine of karma and why it is essential.

Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem

Essentially each practitioner of Buddhist meditation makes the journey alone, but many find that committing themselves to the three jewels—Buddha, dharma, and sangha—helps take them further. These three make up the lineage, philosophy, and community of Buddhism, explains Christina Feldman, and their purpose is to deepen and expand our practice.

What is Interdependent Origination?

Interdependent Origination as defined by Francesca Fremantle, a scholar and translator of Sanskrit and Tibetan works.

Buddhism A–Z

Explore essential Buddhist terms, concepts, and traditions.